How does one stage Chekhov? His plays, embodying symphonic realism and equipped with precise visual and aural effects, would seem to defy massive reinterpretation. Yet we live in an age of director’s theatre and Benedict Andrews with Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard and Katie Mitchell and Jamie Lloyd with The Seagull have all, with varying degrees of success, offered distinctive visions of the plays. Next month sees another Seagull, “conceived and directed by Thomas Ostermeier”, coming to London’s Barbican with a cast headed by Cate Blanchett and Tom Burke. As a great admirer of Ostermeier’s radical updates of Ibsen – especially An Enemy of the People – I shall be fascinated to see how far he goes with Chekhov, in an adaptation by Duncan Macmillan.

Having seen a flock of Seagulls over the years, I am struck by the seismic impact of small differences: in other words, casting, context and interpretation of character can alter one’s perspective without disrupting the period or setting. The first Seagull I ever saw, as a student critic, was an Old Vic production by John Fernald that opened at the Edinburgh festival in 1960. It was everything I had imagined classic English Chekhov to be except for one thing: the fact that Konstantin, the struggling young writer, was played by a 23-year-old actor fresh out of Rada and with a strong northern accent.

His name was Tom Courtenay and he was astonishing: gaunt, unromantic and suggesting what Irving Wardle called a “prickly provincialism”. It was the start of an illustrious career but, reading Courtenay’s memoir, it is intriguing to learn the conditions attached to his casting. Michael Benthall, who ran the Old Vic, had told him: “You can play Konstantin in The Seagull but not with those teeth,” and the young Tom was promptly dispatched to Harley Street for expensive dental surgery.

In Edinburgh, that production was overshadowed by being followed at the Lyceum by a late-night revue, Beyond the Fringe, that launched a tsunami of anti-establishment satire. By a nice irony one of the Fringe foursome, Jonathan Miller, himself turned into a pioneering interpreter of The Seagull, which he later directed at Nottingham, Chichester and Greenwich. It was that last production in 1974 that was most radical because of its context. Miller played The Seagull as part of a cross-cast season that included Hamlet and Ghosts and in each case you saw a son (played by Peter Eyre) suffering an Oedipal attachment to his mother (Irene Worth) and resenting her new companion (Robert Stephens). But that wasn’t Miller’s only original idea. He took seriously the theme of the play Konstantin stages in the first act – the idea that body and soul will ultimately merge in beautiful harmony – and suggested that the reconciliation of matter and spirit resonated throughout the text.

My belief that you don’t have to rewrite the play to find new approaches is confirmed by Michael Frayn, who has argued that Chekhov’s moral neutrality means that “nothing is fixed: everything is open to interpretation”. It was a memorable Terry Hands production for the RSC in 1990, using Frayn’s translation, that opened my eyes to something else about The Seagull. It helped that Hands had a dream cast: Susan Fleetwood as Arkadina, Amanda Root as Nina, Simon Russell Beale as Konstantin, Roger Allam as Trigorin. But Hands’s most original idea was to place the interval late on between the third and fourth acts when there has been a two-year time-gap in the action. One suddenly saw that characters like Arkadina and her lover, Trigorin, remained permanently locked inside their own egos while the two people who had shown a capacity for change, Konstantin and Nina, became quintessentially tragic.

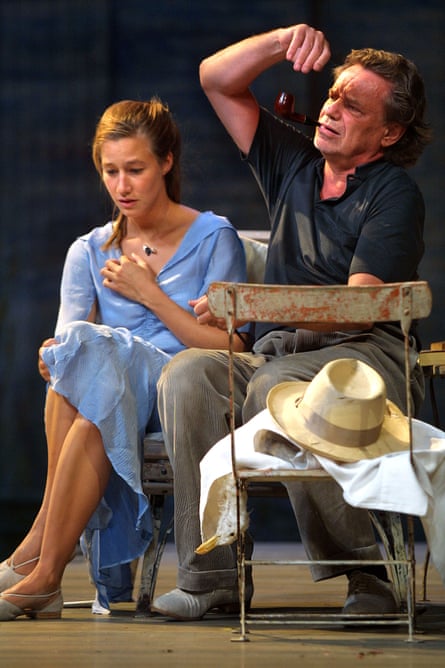

Luc Bondy, in a production for the Vienna Burgtheater that came to Edinburgh in 2001, followed Hands’s example by taking a late interval. Although the production was set in an indeterminate modern world of sunglasses, high heels and refrigerators, it was totally faithful to the spirit of the play and boasted a revelatory performance by Gert Voss as Trigorin. Instead of playing the character as a grizzled sensualist, Voss presented a figure of crumpled quietness and extreme shyness who was a passive observer of life. His famous confrontation with Nina, as he lectures her about the unglamorous nature of writing, acquired a whole new meaning: squatting beside her on a sun-lounger, Voss nervously put a hand behind her back only to find her suddenly collapsing into his arms in a dead faint. What we witnessed was the accidental descent of lust leading ultimately to Nina’s ruination.

The late Bondy had a public falling-out with Ostermeier when the latter suggested that directors over the age of 40 should retire because they gradually lost touch with reality. Now that Ostermeier himself is past 40, I am sure he has recanted. Since he has directed The Seagull many times before, in Amsterdam, Paris, Lausanne and Berlin, he clearly loves the play and I trust he will bring to it that sense, present in all the best productions, that we are eavesdropping on life as it is confusingly and erratically lived.

-

The Seagull is at the Barbican, London, from 26 February to 5 April.

.png) 3 months ago

42

3 months ago

42