Down an easy-to-miss turnoff on the A48 just outside Chepstow on the Welsh border, the gentle rumble of trucks, cranes and people at work mixes with birdsong in what is an otherwise peaceful rural setting. It is a crisp and sunny winter morning when I visit and, at first glance, the site appears to be little more than prefab containers and a car park. Yet, behind the scenes a group of men and women with expertise in diving, marine biology, technology, finance, construction and manufacturing are building something extraordinary. They have come together with a single mission statement: to make humans aquatic.

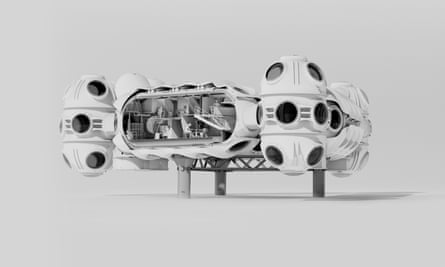

Their project is called Deep (not The Deep) and the site was chosen after a global search for the perfect location to build and test underwater accommodation, which the project founders say will enable them to establish a “permanent human presence” under the sea from 2027.

So far, so crazy sounding. Yet Deep is funded by a single anonymous private investor with deep pockets who wants to put hundreds of millions of pounds (if not more) into a project that will “increase understanding of the ocean and its critical role for humanity”, according to a Deep spokesperson. Its leadership team remains tight-lipped not only about the amount (they will only say it is substantially more than the £100m being invested into the Deep campus near Chepstow), but also about the investor’s identity. Whoever is behind it, the size of the investment means that an ambitious-sounding idea appears to be swiftly becoming a reality.

-

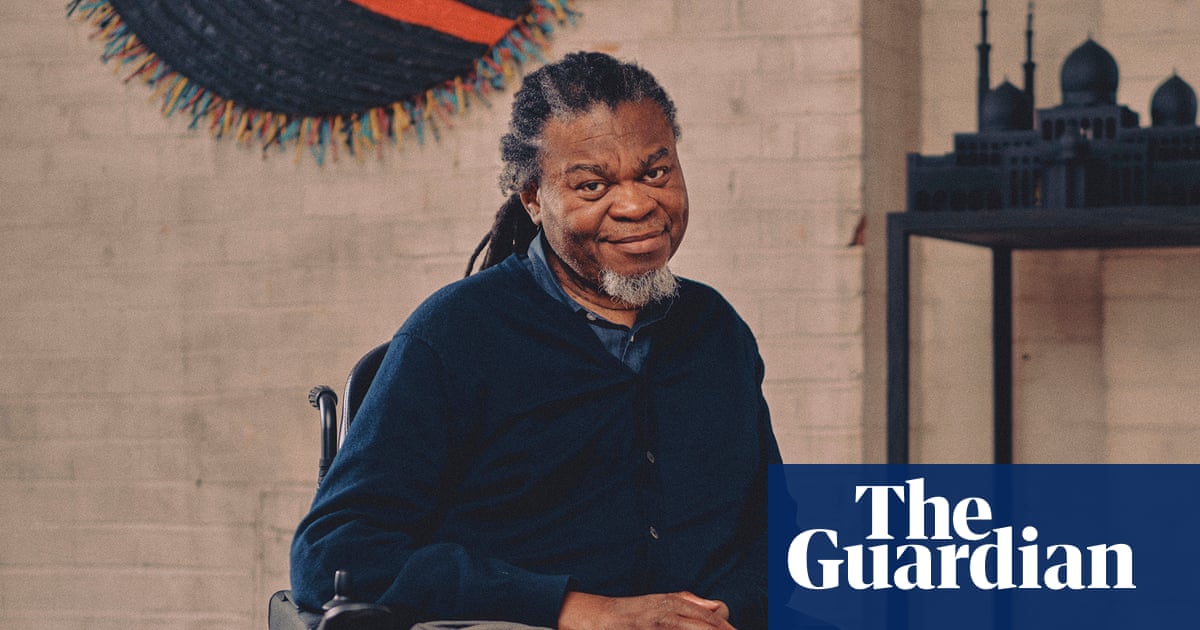

Phil Short, research diving and training lead at Deep, outside the full-scale replica of the subsea sentinel habitat under construction at a site on the Welsh border. Photograph: Mark Griffiths/the Observer

The 20-hectare (50-acre) site in Gloucestershire was once a limestone quarry that was flooded in the 1990s and used by a dive school until 2022. Now, it is being transformed into a state-of-the-art facility that will feature accommodation units, a training school and a platform for mini submersibles to take people down to living spaces in the 80-metre deep (260ft) lake. These underwater units, known as sentinels, will then be used to train scientists – and eventually anyone else who has the money to rent them – to live under the ocean for much longer than has ever been achieved before, and at a greater depth.

The units can be lowered to 200 metres (656ft) under the sea, which is where the sunlight zone ends and the twilight zone of the ocean begins. Marine life found at that depth includes the kind of creatures most people will only ever see via David Attenborough documentaries and is a place about which we still know very little.

Mike Shackleford, Deep’s chief operating officer, explains the thought process behind the project. “Back in the 1950s and 60s, there was a space race and an ocean race going on, and space won out. Space is tough to get to, but once you’re up there, it’s a relatively benign environment.” The ocean is the opposite: it’s fairly easy to get to the bottom, but once you’re down there, “basically, everything wants to kill you”, he jokes.

“Yet, just about every oceanographer I’ve met says, ‘You’d be shocked at how little we know about the ocean’,” Shackleford tells me. “So somebody has got to take those first steps to try to build some of the technology that will allow us to go down and study the ocean in situ.”

The idea of Deep’s sentinels is that, initially, people will be able to stay inside for up to 28 days at a time – though the hope is that this could one day be extended to months … and beyond. “The goal is to live in the ocean, for ever. To have permanent human settlements in all oceans across the world,” says Shackleford.

-

Jacques Cousteau led a group of ‘aquanauts’ in an underwater habitat in the Red Sea in 1963, proving that such expeditions were possible. Photograph: Robert B Goodman/National Geographic Creative

There have been previous attempts to establish living quarters in the sea. Jacques Cousteau pioneered underwater living in the 1960s, starting with the Continental Shelf (or Conshelf) I, a five-metre long, 2.5-metre wide steel cylinder that was set up off Marseille at a depth of 10 metres. Cousteau went on to develop more sophisticated versions of Conshelf I at locations around the world – funded in part by the French petrochemical industry.

Cousteau eventually abandoned it for a career focused on conservation but underwater habitats remained popular for some time after, inspiring all sorts of experiments, including one by two British teenagers who lived underwater for a week off the coast of Plymouth in a steel tank they had built themselves. The craze to conquer life under the ocean then “dropped off in the 80s”, says Shackleford. “Humanity kind of walked away and went towards outer space.”

-

Nasa’s Aquarius Reef Base in the Atlantic Ocean in the Florida Keys national marine sanctuary, built in 1986, is still in use. Photograph: J Marshall/Tribaleye Images/Alamy

The last and most sophisticated undersea habitat was the Aquarius Reef Base, five miles off Key Largo in Florida and 19 metres under the surface. Now run by Florida International University, it was built in the 1980s and is the only underwater human habitation still used today, including for the training of Nasa astronauts as part of the space agency’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations’s (Neemo) programme.

Back in Gloucestershire we pile into a Land Rover to begin the bumpy ascent up the track that loops round the lake where, as we near the clearing at the top, we are greeted by shouting, banging and the sound of electric drills. Everything being made by Deep is being constructed either on site or down the road at an industrial unit in Bristol, including the lifesize wooden mock-up of the sentinel that we are driving to see.

-

‘The perfect location to build and test underwater accommodation’: Deep’s site at a quarry lake in Gloucestershire. Photograph: Richard Varcoe/Deep

-

The habitat simulator, a full-scale replica of Deep’s subsea human habitat, will be used to train divers on land before they live below the water. Photographs: Mark Griffiths/the Observer

Standing outside the full-size underwater house gives an instant idea of the incredible scale of the undertaking. The main recreational area is a six-metre diameter hemisphere, and the porthole windows mean that when the real thing is submerged there will be an inescapable feeling of being surrounded by the ocean and its inhabitants.

Upstairs is a kitchen and an area that can be adapted to scientific study. The six bedrooms are roomy and there is a fully fitted bathroom with running water and a flush toilet. The whole thing is constructed from a type of steel specially developed to withstand the pressure at 200 metres.

Although no one working on deep-sea submersibles wants to dwell too much on the Titan tragedy – the deep-sea submersible that imploded off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, in 2023 killing all five people on board – Phil Short, research diving and training lead at Deep, is not surprised it’s a subject that keeps coming up. One of his primary concerns is to underline strongly the difference between this project and that of the Titan.

Deep’s engineers have been working with Det Norske Veritas (DNV), a classification and safety agency, to ensure it is fully tested and certified all the way through the design and manufacturing process. “DNV are approving every potential design, manufacture and testing capability of our systems from day one,” Short says. “So, when we finally get this built and we’re about to drop it in the water, it will be fully certified in class.”

-

The two-person mini submersible is prepared for deployment at the edge of the lake. Photograph: Richard Varcoe/Deep

Classing is like an MOT on a car, he says: “No one reading this would think of putting their children, their partner, their family dog, in a homemade car with no test, unknown brakes, unknown gearbox, unknown engine and homemade tyres.” They would, he says, choose something based on how well it will protect those people.

The equipment might be certified, but what about the people who will be using it? It will be a huge task to physically and mentally train those without any experience for life under the water. Even looking at the two-person mini submersible they have waiting for deployment at the edge of the quarry lake, I think, could I really trust it to take me a few metres below the surface of a lake, let alone convince myself to travel hundreds of metres under the sea?

The philosophy behind how successfully an individual will cope, says Short, is much the same as that for training soldiers: you can do as much basic training as possible but until you’re in a firefight you don’t know how you’re going to respond. However, the advantage of having a simulator that pretty much exactly replicates life underwater, means Deep’s dive-training team are better able to put people through their paces.

“We can basically cover that psychological aspect of: how do you feel being stuck in an environment about the size of a small family home with five other people for 28 days? We can trial that thoroughly,” says Short. He estimates it will take anywhere between a year and 18 months to get someone who has never dived before fully capable of running an ocean deployed sentinel system.

Dawn Kernagis is director of scientific research for Deep. We meet in London, at the end of a trip she has taken from her base in the US to see how progress is coming along at Deep campus. Kernagis was a crew member with the Nasa Neemo mission that lived aboard the Aquarius Reef Base and so has rare first-hand experience of living underwater.

“I can still visualise what it was like to wake up in the morning there,” she says. “We had the window just next to the bed and so you would open your eyes and see fish, stingrays and sharks swimming by. Being able to watch those interactions was just so key. Because, you know, we weren’t disturbing their environment, they were just doing their thing and it’s really cool to have the capability to observe that.”

-

Mini submersibles will take people down to living spaces in the 80m deep (260ft) lake. Photograph: Richard Varcoe/Deep

Deep will offer the same experience but with more sophisticated accommodation, at greater depths, and allow scientists to work at those depths for greater periods of time. Their sentinels will also be able to be redeployed to different places. The idea is that a foundation construction will be attached in the desired location at the required depth and then the sentinels will be lowered down to click into the base like “a ski boot being locked into a ski”, Kernagis says. The basic sentinel houses up to six people but the idea is that multiple sentinels could be attached to potentially form multi-nation, multi-purpose research stations (or perhaps, one day, an underwater village for ordinary people).

In the past, a lot of the early underwater habitats were meant to be redeployable, but it was difficult to do that, so they would be put down in one place and stay there for years. “You’re restricting what marine science you can do if you can only do it from one place,” Kernagis says.

-

The sentinels will include a kitchen, study area, six bedrooms and fully fitted bathroom

Kernagis, who has a background in human physiology, is excited about being given the ability to learn more about the human body and what living at depth does to it. Much research into the effects of saturation diving on the human body was done in the 1970s and early 1990s but it tended to be on young, physically fit men, she says. The ability to revisit some of that work with a wider variety of people and to do it in situ, rather than potentially compromising samples by bringing them to the surface, is going to enable better science.

Kernagis thinks the relative comfort of the accommodation provided by Deep will help anyone using it. Aquarius, for example, used a bunk-bed system with six people sleeping in one tiny space. “Living under pressure like that, some people tended to snore louder than normal,” she says, “so we tended not to sleep as well.” Then there were the questionable bathroom facilities. “We had a toilet that was actually part of the shower and was in the moon-pool area, which is where you go in and out for your dives. And so everything was just a curtain that you pulled. And that was it.”

Deep’s toilets, a spokesperson assures me, have been through “extensive human factors assessments to ensure that they are as comfortable as possible”.

Across the River Severn from Gloucestershire in a commercial kitchen in Avonmouth, Bristol, chef Joe Costa is trimming carrots to use in the main course of an experimental dish. An underwater menu is one of the final, but crucial, pieces of the puzzle that Deep is working on to make life under the sea the best it can be.

“The first hurdle was the challenge of actually being able to taste anything at depth because your tastebuds are suppressed by the pressure change,” says Costa, a classically trained chef and a diver.

He is focusing on using strong flavours that will be delivered in vacuum packs. His initial menu sounds mouth-watering and he makes it more tantalising by describing it like he is presenting it on an episode of MasterChef.

“We start with a french onion soup, with nice cheese croutons on the top, and then we have slow roast, short-rib beef that has been marinated for a week in a sous vide (vacuum-sealed bag) in a really heavy red wine sauce. That is served with a truffle polenta with ricotta and then, to finish, a double sticky toffee pudding, which is spiced with extra cinnamon, all spice, and star anise.”

-

Porthole windows mean those within will be surrounded by ocean life. Photograph: Mark Griffiths/the Observer

-

Chef Joe Costa’s first attempts at presenting vegetables that are both visually appealing and easy to stow; the dive centre on the full-scale sentinel mock-up. Photographs: Joe Costa; Mark Griffiths/the Observer

If this sounds hugely calorific, it’s because it is. Phil Short, who at 56 boasts an impressively skinny frame, explains that as soon as anyone gets in the water, even if it’s warm, they start losing heat rapidly and their lungs have to work harder against the pressure of the water. This raises the body’s metabolism significantly, and that’s before any physical exertion has taken place. “I’ve spent my whole life in the water and I eat and eat and still lose weight,” he says.

A lot of the food Costa is preparing tastes too strong above the water. The beef in the sauce was wonderfully tender but “hard to palate” he says. Yet at depth it should hit people’s tastebuds in just the right way. And he’s thought of every detail to make a culinary underwater experience the best it can be. “We are thinking about doing sous vide cheese snacks as an appetiser so that when the divers come into the sentinel, they get their wet gear off and get changed and can have a little cheese board before they start their meal.” All that’s missing, it seems, is a glass of red wine.

Once Costa has created the menus they will go to a nutritionist to assess them for the required levels of vitamins and minerals and finally they will be tested under pressure in a laboratory in a diver research centre in Plymouth. Short is unapologetic about the apparent extravagance of the food on offer. “They say an army marches on its stomach, so quantity, quality, taste and also ease of digestion are all massive factors to make these missions successful,” he says. “And, more importantly, for the type of people we want to put in these habitats it makes meals enjoyable, rather than just miserable.”

-

Deep’s engineers are working to fully test and certify the structure through each stage of the design and manufacturing process. Photograph: Mark Griffiths/the Observer

Everything about Deep – the Gloucestershire campus, the size and scale of the underwater accommodation, the food and the anticipated clientele – appears to be pushing the boundaries of what has gone before. But one thing remains constant, and that is what is waiting in the watery world below for those who brave life in the underwater housing.

“There are going to be things down there that we won’t even know to ask questions about before we descend, because we don’t know yet that they exist,” says Kernagis.

This potential is what makes work under the ocean so exciting for her. She recalls her time towards the end of the mission on the Aquatic Reef Base when she made an excursion with a colleague in one of the submersibles outside the main habitat.

“We were wrapping up some of our sample collections and I made the comment to her that I couldn’t imagine life back on Earth. And she turned to look at me and said, ‘We are on Earth’. But for me it was like I was in this whole other world.”

.png) 2 months ago

47

2 months ago

47