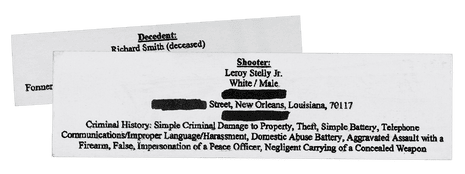

Over a roughly 14-year period beginning in 2009, Leroy Stelly Jr faced accusations of pepper-spraying two women whom he encountered on a sidewalk and insulted as “bitches”, slapping his future wife at a bar, and threatening to shoot a construction worker while pretending to be a cop.

He also called emergency operators and declared that he was “going to put a fucking .45”-caliber bullet in the head of someone who had banged on his door. He allegedly punched a guest he had over on Christmas Eve. He reportedly challenged people at a healthcare clinic with which he shares a fence “to meet [him] out on the street”.

And, finally, he shot his neighbor to death on the sidewalk outside his place in New Orleans while claiming he was standing his ground.

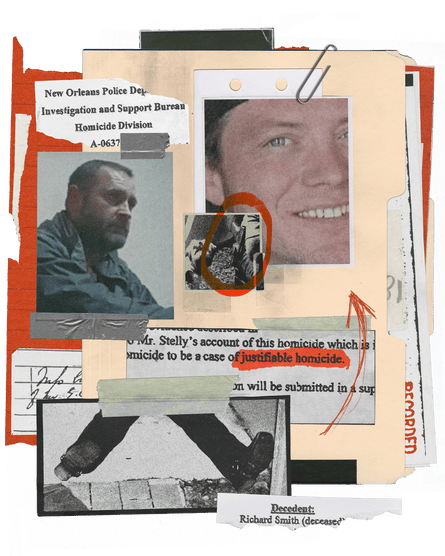

No one has ever filed criminal charges – or even civil litigation, given Stelly’s relative lack of assets – in connection with the fatal 7 January 2023 shooting of Richard Bernard “Richie” Smith, 38, which authorities have deemed justified.

However, Smith’s loved ones have never accepted that outcome as valid, instead urging investigators to more zealously scrutinize Stelly’s history of alleged violence – and to weigh that against claims that he had to kill to save his own life.

With the help of a precious few close allies, Smith’s mother, Dana Leonard, has mounted her own investigation into her child’s slaying as well as the man who ended his life. It is summarized in an 80-page report which she presented to police and prosecutors, highlighting Stelly’s past alleged criminal behavior, his shifting story about Richie’s last moments and factors which investigators did not explore.

The only conclusion at which she can arrive: a perennially understaffed police department – grappling in those days with being the US’s murder capital – botched an investigation into a killing that she maintains was unjustifiable and illegal.

Leonard empathizes with what police were up against. No one else witnessed Stelly fatally shoot Smith with a .45-caliber handgun. Investigators concluded that no surveillance camera recorded any footage of the killing.

And, in the eyes of much of the rest of the world, the US has remarkably permissive laws regarding firearm possession and self-defense. They collectively create a political environment in which people believe they can fire guns at others with impunity in many situations – and often have an easy time convincing law enforcement of that.

Louisiana, to boot, is widely seen as having one of the most permissive justifiable homicide – colloquially, “stand your ground” – laws.

Nonetheless, with every fiber in her being, Leonard suspects that “Leroy murdered Richie”. And if he didn’t, she said she is unconvinced that Richie needed or deserved to die by Stelly’s hand.

And, just as fervently, she believes detectives are simply not following the evidence by which they could try to pursue justice for her son.

Attempts to contact Stelly, 46, were unsuccessful. His wife, who was with him the night he killed Smith, did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Neither did the local district attorney’s office.

In a statement, New Orleans police said they had “thoroughly investigated this case” on multiple occasions. “And each time, the conclusion was the same – the case was deemed as a justifiable homicide,” the police’s statement said.

Police said they worked with “diligence and integrity” but could not secure evidence in support of murder, manslaughter or negligent homicide charges, though they would be open to analyzing any new evidence that might materialize in the future.

“We understand the victim’s family is dealing with terrible loss and is seeking justice,” police said. “As a police department, we witness the pain that tragedy brings to families, and we carry a deep sense of responsibility in seeking truth and accountability. At the same time, we recognize there are moments where the justice families hope for may not come in the form that they want or need.”

‘I’m standing my ground’

Louisiana’s legislature enacted its stand your ground law in 2006, allowing people who reasonably perceive their lives to be in danger to resort to lethal force without a duty to try to retreat first as long as they are somewhere they can legally be.

Already on Louisiana’s books was the so-called “castle doctrine” law, which enabled property owners to defend their belongings against anyone trying to intrude and placing them in imminent danger without their first needing to attempt a retreat.

And the burden is on state prosecutors to disprove all claims brought to criminal court under the castle doctrine as well as stand your ground laws. That can create a legal climate in which state prosecutors are apprehensive about pursuing cases that aren’t “totally cut and dried”, said Joseph Giacalone, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and retired New York police department detective sergeant who formerly supervised cold homicide case investigations.

Still, William & Mary Law School professor Cynthia Ward said “reasonable” and “imminent” are the operative words for the fear of safety and danger that self-defense claimants must cite. Self-defense claimants must also not have provoked the situations making them fearful of their lives, Ward said, a concept to which she referred as “bringing on the trouble”.

“Many people … don’t really understand that you can’t just take out your gun and shoot someone just because you believe you might be at risk,” said Ward, a specialist in criminal responsibility. “Justified self-defense is an exception to the general rule that you are not allowed to use physical force against other people.

“It’s only in cases of absolute necessity.”

If a 911 call that he made five months before he killed Smith is any indication, Stelly evidently had a liberal interpretation of those concepts.

Stelly dialed emergency operators in August 2022 to complain that a man in the neighborhood had banged on his door. He quickly told the call-taker: “I am armed, and I’m fixing to use it. My weapon is on me, and I’m sitting on my front stoop, practicing both the castle doctrine, the ‘stand your ground’, and everything that I can.

“He’s in danger if he comes back across the street. I’m going to put a fucking .45 in his head.”

The 911 operator implored Stelly to lock himself inside his house. “I’m standing my ground,” Stelly retorted, while also surmising the man who had banged on his door was a “dopehead” having something to do with the nearby health clinic, which he dismissed as “a needle exchange”.

It was not the first time Stelly had threatened violence. In some instances, he had even allegedly inflicted it.

In 2009, while wearing the uniform for his private security job, Stelly purportedly walked past two women on a sidewalk, called them “stupid bitches” and pepper-sprayed them after they told him to not speak to them like that, according to a lawsuit that was filed later. A police officer who noticed the injured women arrested Stelly on two counts of second-degree battery, court records show.

One of those women, Cassidi Townsend-Epherson, recalled claims from Stelly that his reaction resulted from “a fear for his life”.

During a more recent interview, Townsend-Epherson said she was incredulous at the defense. She remembered how she was “giggling” with her friend and a third woman about the good time they were sharing together when Stelly, without provocation, bumped into them.

“He couldn’t have possibly been in fear for his life,” Townsend-Epherson said. “We had nothing on us – I don’t even think I had my purse on me.”

On the other hand, to her, it appeared Stelly was “in a manic state” while also reaching for a gun before the officer who arrested him arrived in the nick of time and prevented the situation from spiraling out of control.

Stelly later opted for a trial by judge rather than jury. The case culminated in New Orleans criminal court judge Benedict Willard acquitting him.

Making matters worse for Townsend-Epherson, the lawsuit that she and one of the other women subsequently filed against Stelly’s employer was dismissed after the company argued in court filings that it was not liable because Stelly was not at work at the time of his arrest, according to records.

“It was so insane to me … because I’m thinking, we were just small girls, and he … almost made it sound like he had the right to do what he did because we were smart-mouthed to him,” Townsend-Epherson said.

Then, in a bar in 2017, Stelly allegedly slapped the woman he would later marry in her face, getting himself booked on suspicion of domestic-abuse battery. Prosecutors ultimately refused to file charges.

In 2019, Stelly boasted that he was a cop, told a worker at a construction site, “I will shoot you,” and was charged with counts of false impersonation of a peace officer and aggravated assault with a firearm, police said. He pleaded guilty to lesser charges in exchange for probation.

On Christmas Eve about four months after his August 2022 emergency call, about two weeks before Smith’s slaying, a guest of Stelly dialed 911 and reported being punched by his host. Stelly was not arrested.

Emergency operators received another call about Stelly on 5 January 2023, this time from officials at CrescentCare, a health clinic that shares a fence with his back yard on Marigny Street in New Orleans’ St Roch neighborhood.

Those at the facility reported Stelly was spraying people with a hose. On a recorded call, one doctor said Stelly “was threatening to meet people out on the street”. The official added that Stelly “literally stuck the hose through the fence and proceeded to try to soak” someone with it.

In a separate statement to the Guardian, a CrescentCare spokesperson accused Stelly of using “racially derogatory language” before he started spraying the garden hose at staff. The spokesperson said police instructed Stelly to leave those at the clinic alone. Officers also encouraged the facility staff to file a formal report, which they did, though Stelly was not arrested.

The next time Stelly would speak to police would be less than two days later – after shooting and killing Smith.

‘Did what I had to do’

Smith had moved to New Orleans from Ojai Valley, California. On the last day of his life, when he left his job bartending, stopped in another establishment for a nightcap and headed home, his adopted city had just finished a third straight year in which the annual number of homicides had increased.

That had left New Orleans saddled with the unwanted title of the US’s murder capital.

Simultaneously, for much longer, New Orleans’s police force – which the city considers one of its most vital components in the battle to hold criminals accountable – has been hundreds of officers below its ideal staffing level.

And it fell to a detective who worked 11 new homicide investigations that year – more than the annual allotment of four to six such cases recommended by the Police Executive Research Forum, a national non-profit thinktank based in Washington DC – to probe exactly how Smith’s life was cut short on a sidewalk across the street from his home.

Carrying a tote bag with some food, a paycheck from his second job at a restaurant and a hatchet that he carried for protection, as was his legal right, Smith took a route home which brought him past Stelly’s place across the street. Stelly was on the sidewalk when Smith’s path crossed his at about 1.30am.

After shooting Smith, Stelly called 911 and said: “I just shot a person who was attacking me as I was going into my side yard.”

Stelly said he announced to that person that he was armed and was at his home. But Stelly claimed the other man shrieked, “I will fuck you up,” and then advanced.

“He approached quickly, and he raised his hands towards me, and my life was threatened at this point,” Stelly was heard saying on a recording of the call. “So I did what I had to do.”

The emergency operator asked Stelly whether he would grab a towel and apply pressure on the wound of the man he had shot. “I am not doing that – no ma’am,” Stelly replied. “I am not a medical professional. I am not a medical professional.”

Stelly would later tell the lead detective on the case, Michael Poluikis, during a recorded interrogation that he was outside his home to change a gate lock when he ended up arguing with a man who approached him.

“He went to reach forward, and that’s when I drew the weapon,” Stelly said.

Separately, Stelly’s wife, Sarah, gave a slightly different account. Sitting in the back of a police car after first responders had been summoned to the scene of Smith’s shooting, Sarah Stelly told Poluikis that her husband had gone outside to get firewood from her car.

Sarah Stelly said she heard her husband tell someone to “stand down” before a gunshot, according to video captured by a body-worn camera equipped on a colleague of Poluikis’s.

Crime-scene photos established Smith had dropped a cigarette at his side and his tote bag to the ground at his right foot. The cigarette was still lit near his hand, which made it seem as if Smith had been shot while smoking. The hatchet handle was sticking out of the bag, though it clearly remained inside and was not in Smith’s grasp.

“I did what I had to do,” Stelly repeated to Poluikis.

Poluikis, who has since left the police department and moved out of state, obtained warrants to search Stelly’s phone as well as to recover any relevant neighborhood surveillance camera footage. An ensuing police analysis determined neither line of inquiry had produced evidence of a crime.

“Detective Poluikis believes this homicide to be a case of justifiable homicide,” the investigative report said.

That finding was not good enough for Leonard, Smith’s mother.

Inconsistencies

Leonard and Smith’s father, Andy, hired a private investigator. They and their supporters set out to prove there was much more to the story than police indicated.

For one, Stelly and Smith had lived across the street from each other for the better part of a year before the former killed the latter. They would greet each other whenever they did yardwork outside their homes at the same time. And others in their households were familiar with each other, too.

So much so that the Stellys had invited Smith as well as his roommate over to a party in the hours before the killing, according to information Leonard received as she and Smith’s roommate compiled an 80-page report they would later provide to authorities, including prosecutors, Poluikis’s sergeant and other law enforcement officials.

Furthermore, call logs show that Sarah Stelly called Smith’s roommate twice in the minute before Lee Stelly dialed 911 to report the killing. After learning there had been a killing outside their homes but before authorities confirmed exactly who had been slain, Sarah Stelly also texted the roommate asking whether it was possible that Smith would have not recognized Lee.

The roommate, fearing the worst had happened because Smith never made it home that night, recalled eventually speaking by phone with Sarah Stelly – and then she dialed 911 herself. On the recorded call, the roommate said to the emergency operator: “I talked to my neighbor this morning, and she said her husband shot and killed someone. And my roommate never came home. And they’re freaking out because they think that they killed my roommate.

“And I’m freaking out because I think that they killed my roommate.”

The roommate soon learned it was indeed Smith whom Lee Stelly had killed.

Leonard assessed the texts and the call between Sarah Stelly and Smith’s roommate. And she simply does not fathom how the facts relayed in those communications could support the notion that Lee Stelly might have mistaken her son as a fearsome, unrecognizable stranger.

Additionally, having used public records requests to obtain statements that police recorded in the aftermath of Smith’s killing to prepare their report, Leonard and her companions noted glaring inconsistencies.

They have substantial doubts about Stelly’s assertion that he was changing the lock to his gate when he was ambushed. Stelly told Poluikis that he was changing the lock because he had a hair appointment at 8 in the morning and did not want to bother a house guest sleeping in the front.

But the house guest said he would have had to be at the airport for a 7am flight out of town – if not on the plane itself – by the time Stelly left for the appointment. Sarah Stelly said the same thing.

Poluikis’s report says Stelly told the detective that Smith had reached behind him at some point as if to access a backpack, though he mentioned no such detail on the 911 call immediately after the shooting. Leonard does not think that claim is credible because by all indications Smith’s hands were occupied with the cigarette and tote bag – and Smith did not have a backpack.

Leonard also realized that Stelly was wearing a headlight around his neck in videos of his police interrogation and at least one taken by an officer’s bodyworn camera on Marigny Street. She can’t help but wonder whether Stelly had that light on, obstructing Smith’s view while Stelly could clearly see Smith during their encounter – and whether that escalated tensions.

‘Justice for Richie’

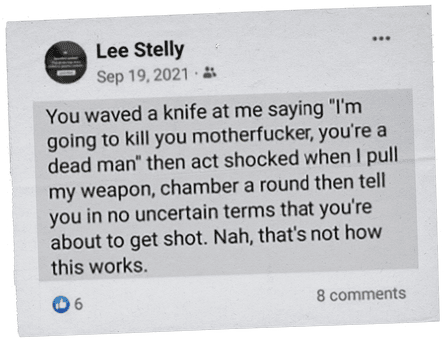

Leonard and her associates also culled copies of social media posts that they argue showed Stelly had vigilante inclinations – as well as pride in his short temper.

A 2019 Facebook post under his name muses that people who run stop signs or otherwise drive inattentively “don’t get to dictate the reaction of” fellow motorists.

“When I choose to call you stupid motherfucker and you decide to stop and defend your stupidity, make sure I’m not armed,” Stelly said. “These assholes always start off by getting out or off of their vehicles ready to fight until they see me chamber a round, then the apologies start.”

In reacting to a July 2022 article from a conservative news outlet about how New York City prosecutors had dropped a murder charge against a Manhattan bodega clerk accused of stabbing a man who attacked him first, Stelly wrote on Facebook: “Hell yeah! Finally some sense out of NY.”

That post came about seven months after another one in which he described almost being carjacked, calling the police and quickly being greeted by an officer. “They went running after my 45 slipped leather,” Stelly said, invoking a phrase that means he pulled his gun out of its holster. He also wrote how he suspected the rapid police response “may have had something to do with me telling the 911 operator that I’m armed and don’t mind using it”.

Meanwhile, Leonard and her associates eventually learned that a friend of Smith had recalled Smith giving him a chilling warning in the last weeks of his life. “Be careful of that guy,” Smith said of Stelly, according to the friend. “He always carries a gun and isn’t afraid to point it at people in the neighborhood and make threats.”

That friend said he called Poluikis days after Smith was killed. He got a return call, but the two did not manage to speak. He wrote an email to police in March 2024 to provide the information he had.

For its part, the New Orleans coroner’s office conducted toxicology tests on Smith and made it a point to report how he had been drinking and therefore accumulated a high blood alcohol content before choosing to walk home.

Smith made that choice about two decades after a drunk-driving arrest. It was the only blemish on his record beside a noise ordination violation for playing his set of drums too loudly, police determined.

Investigators conversely never took steps to determine whether Stelly had been drinking, too, or if he had ingested any other intoxicants, including at the house party he was hosting on the night he killed Smith.

Drawing in part from court documents pertaining to his past, Leonard’s report delves into Stelly’s numerous other brushes with the law. It provides a link to a change.org petition with more than 2,000 people urging officials to not give up on “justice for Richie”.

A civil attorney whom Leonard also consulted talked her out of suing Stelly for wrongful death damages, saying in essence that he wasn’t wealthy enough for it to be worth it. Yet she and her supporters delivered their report to police and prosecutors, asking each to give it a fresh look.

The commander of the police’s homicide investigators assigned a cold-case detective to re-examine the case in about the late spring of 2024. But police have not obtained a warrant to book Stelly with a crime in Smith’s killing. And prosecutors have not taken the case to grand jurors to see if they would hand up charges.

She said: “They told me it would be hard to disprove Leroy Stelly’s self-defense claim beyond a reasonable doubt,” which is the evidentiary standard for a conviction at trial but not for a grand jury proceeding. The standard of evidence for a grand jury to return charges is slightly lower – it can do so if it believes a crime probably occurred.

Though Stelly’s wife remains at the home near where Smith died, Leonard understands Stelly may have moved out of state, too, continuing to live his life unimpeded, at least as it appears to her.

It is a gut-wrenching set of circumstances for at least a couple of people. One is Townsend-Epherson, who said she was terrified to learn about Stelly’s having killed Smith. She said she can’t help but think that she and her companions could have met the same fate as Smith if things had played out differently on the night in 2009 when Stelly bumped into them.

“There’s no way he should have been running around with no consequences for anything,” Townsend-Epherson said. “And now, someone is gone.”

Elsewhere, Leonard said she abides by one of the main opinions contained within the 80 pages of the report produced by the private investigation she helped helm.

And that opinion reads: “Leroy Stelly took a man’s life for no reason other than to fulfill his agenda of policing his neighborhood and bullying the citizens of New Orleans.”

.png) 10 hours ago

2

10 hours ago

2