Alan Hollinghurst’s remarkable new novel, Our Evenings, is many things. A moving portrait of a gay actor, Dave Win, of Anglo-Burmese origin. A state-of-the-nation novel about the transition from the liberated 60s to the period of Brexit and Covid. A study of a changing landscape in which a market town’s identity is forever altered by pizza parlours and supermarkets. But less noticed has been Hollinghurst’s forensically accurate picture of British theatre over the last 60 years. The author’s own involvement in theatre has been mainly as a translator of Racine but he shows an acute understanding of an actor’s psyche and the artform’s politics.

Even Dave’s character is gradually revealed through his theatrical tastes. Early on we learn that at school he longs to play Antonio rather than Fabian in Twelfth Night: the first hint of his sexual inclinations. He shows a talent for mimicking his masters and when he reads a scene with a famous French actor he has a coup de foudre. “In that moment,” he says, “I felt something fizz inside me, a certainty that went beyond acting.” Although ferociously bullied by his school contemporary, Giles Hadlow, and frequently mocked for his ethnicity, Dave discovers himself through role-play.

At Oxford Dave distinguishes himself as Mosca, another shape-shifter, in Volpone but the book’s shrewd understanding of theatre really takes off when the hero joins a touring company, Terra, in the 1970s. It was a vintage time for itinerant groups and Hollinghurst pins down precisely their mix of democracy and despotism: the guiding principles are of openness and maturity but the fictive director, Ray Fairfield, who has worked with Charles Marowitz and knows Peter Brook, rules with a whim of iron. Hollinghurst appreciates one of the great paradoxes of experimental theatre: that collective decision-making coexists with a controlling vision. He even includes a pastiche review, supposedly and plausibly written by me, of a politically disruptive Romeo and Juliet with Dave Win as a dazzling Mercutio.

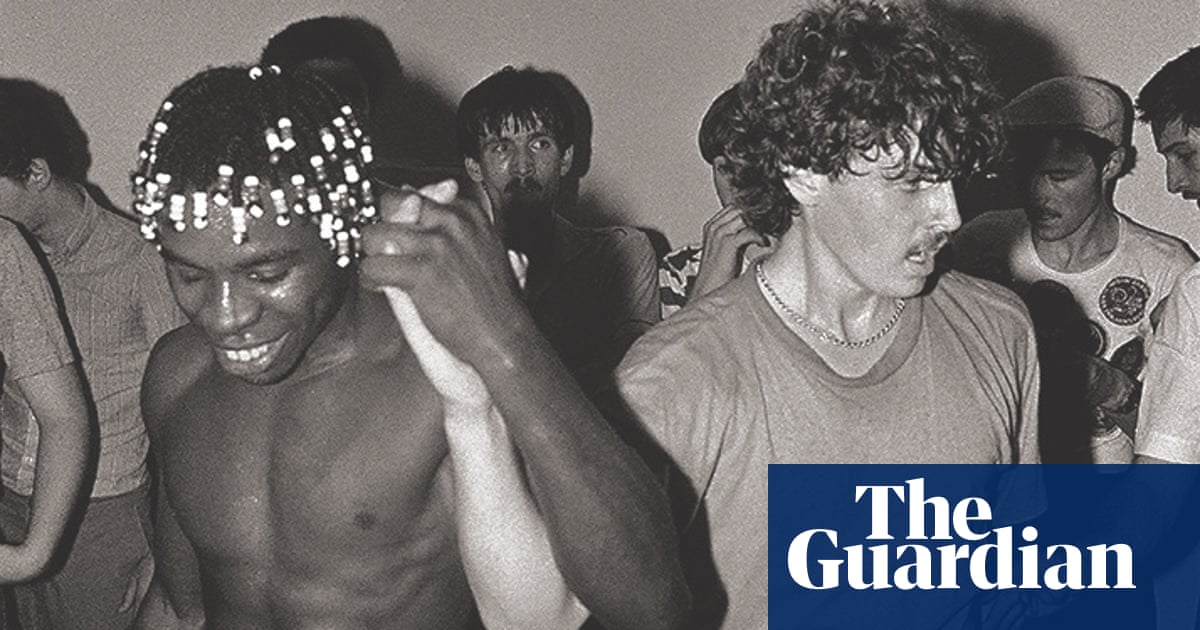

What is impressive is the way Hollinghurst allows his themes of sexual and racial identity to merge seamlessly with his portrait of the realities of British theatre. At one point Dave falls headily in love with a black actor, Hector, just as they are rehearsing a scene in a new play. Ray acidly dismisses their performance as “worryingly self-indulgent” yet their passion is real. But Hollinghurst brilliantly uses the relationship to expose social attitudes of the late 70s and early 80s: both the token liberalism and reflex racism. Hector gets picked up by the RSC but never rises above minor roles such as Barnardo in Hamlet. Happily, this is one area where things have changed in that the big classic roles are no longer off-limits to actors of colour. But there is a bruising moment when, at an after-show party in London, a visiting star hands Hector her coat as if he were a cloakroom attendant and Hollinghurst harpoons the faint element of patronage that often accompanied the casting of black and Asian actors 50 years ago.

Patronage, in the wider sense of the word, is also one of the themes of the novel. Dave himself is the beneficiary of the philanthropy of the wealthy, art-loving Mark Hadlow. The portrait of Mark’s son, Giles, however, is one of the sharpest in the book. He is both Dave’s contemporary and nemesis and ends up in 2012 as Minister for the Arts. Hollinghurst records Giles making a speech pompously claiming that “we are committed to delivering a leaner, better future for our theatres and orchestras and arts organisations”. Hollinghurst then witheringly adds, in Dave’s words, that it was the first time he had heard “deliver” used to mean “take away”.

That is typical of a book that sees through the hollow rhetoric of politicians and the fake democracy of avant garde directors yet shows a passionate understanding of theatre and empathy with actors. Hollinghurst writes perceptively about the ramshackle life of touring and the debilitating knowledge that you are in a cast-iron flop. At the same time, he sees theatre as an undistorted mirror of the age and as a place where, by inhabiting other people, you possibly reveal your authentic self.

.png) 3 months ago

31

3 months ago

31