I am a blue-blood Afrikaner, at least in terms of ancestry: both my grandfathers were young Boer soldiers in the Anglo-Boer war and I am directly related to the president of the old Transvaal Republic, Paul Kruger. I am a descendant of Dutch, French and German settlers who were brought to the southern tip of Africa in the 17th century. Unlike other colonial societies in Africa, my ancestors never left.

They occupied the whole country, displacing and oppressing the Indigenous inhabitants. Eventually, their concept of white supremacy developed into a formal state policy, apartheid. The UN classified this as a crime against humanity. Miraculously, my country has been a thriving democracy and open society ever since the formal end of apartheid in 1994.

Imagine my bewilderment when Donald Trump and his “first buddy”, South African-born Elon Musk, declared that we Afrikaners are a threatened species; that our black compatriots are engaged in a “genocide”; that we are victims of oppression and discrimination and as such offered special refugee status in the United States – at the very point in time that thousands of migrants to that country are being repelled or deported. The US state department is even preparing “refugee centres” in Pretoria to house these “victims”.

The criticisms and threats coming from Trump, his secretary of state, Marco Rubio, and Musk outraged the majority of South Africans because the claims were patently false and were seen as unacceptable meddling with internal affairs. A section of the white population, however – the ethnic Afrikaner nationalists and separatists – welcomed the US intervention, leading to harsh exchanges with racial undertones on social and other media.

Just for the record: Afrikaners are generally better off today than prior to 1994, when they gave up political power; materially, culturally and in terms of personal freedom.

South Africa’s progressive constitution with its extensive bill of rights is intact; the rule of law is maintained and the judiciary is independent and functioning; we are a genuinely open society with free speech and media that many other democracies, especially Trump’s America, can be jealous of.

Whites (about 7.3% of the population) still dominate the economy and own about half the land – and not one square inch of it has been confiscated from white owners. White unemployment stands at 7% with the national figure at more than 30%. The crime rate in the predominantly white suburbs is minuscule compared with that in the vast black townships.

South Africa is ruled by a government of national unity, a coalition between the ANC and the white-led Democratic Alliance, whom the president, Cyril Ramaphosa, chose to partner with instead of the two black nationalist parties, the MK and the Economic Freedom Fighters. The former leader of the predominantly Afrikaner party, the Freedom Front Plus, Pieter Groenewald, is one of several white members of Ramaphosa’s cabinet. Genocide? Victims?

It’s true that the ANC-led governments of the last two decades have, to put it mildly, not performed brilliantly. We had a decade (2009 to 2018) of scandal known as “state capture” under the previous president, Jacob Zuma, and the country hasn’t yet recovered from that completely. There was a deterioration of infrastructure and inner cities, there are almost daily reports of corruption, crime is not under control and economic growth has been at around 1%.

But these are our problems, effecting all our citizens. We don’t need Trump’s or Musk’s help.

Where does their interest in our country come from? South Africa irritated the US and other western governments when it took Israel to the ICJ (international court of justice), alleging genocide in its war in Gaza – Trump made this clear in his executive order on South Africa. The scale of that conflict demanded that someone took the matter for international adjudication, and it was appropriate that it be done by a nation that had overcome dehumanisation, forced removals from land, and gross human rights abuses. History, I believe, will be kind to my country on this score.

But Trump’s expressed anger is mainly directed at the treatment of Afrikaners, a group of people he’s probably never thought of before Musk became his confidant. Why this fixation? Three letters: DEI. Diversity, equity and inclusion. In South Africa, it is called black empowerment and affirmative or corrective action: attempts to speed up the recovery from centuries of dehumanisation, exclusion from the economy, and job reservation.

South Africa has been blessed and cursed because its history and demographics reflect the great themes of human experience. Blessed because the crudeness and cruelty of racial apartheid offended so many people around the world that the international anti-apartheid movement became powerful and white-run South Africa was isolated through sanctions and boycotts. Cursed because the global hard-right has found a seductive narrative – in the current era of immigration pressures and rising ethnic nationalism – in a white minority that is portrayed as endangered. The message is that the supposed fate of Afrikaners in South Africa will be that of white conservatives in the US unless something is done.

I get the sense that fellow Afrikaners are bemused by the offer of refugee status. I think the overwhelming response is “thanks for asking, but no thanks”. We named our tribe after the African continent. Most of us, even those who deeply resent our government and its policies, regard ourselves as pale-skinned Africans. We passionately love our expressive, earthy language, Afrikaans, that is only spoken here and in neighbouring Namibia; it is the most important part of our ethnic identity.

The Trump administration’s threatened sanctions against our country are going to hurt. The best among us Afrikaners and other white South Africans join the rallying call against this foreign interference to galvanise our entire society and to show ourselves and the world that we can be a harmonious and successful country. Donald Trump and Elon Musk don’t speak for us.

-

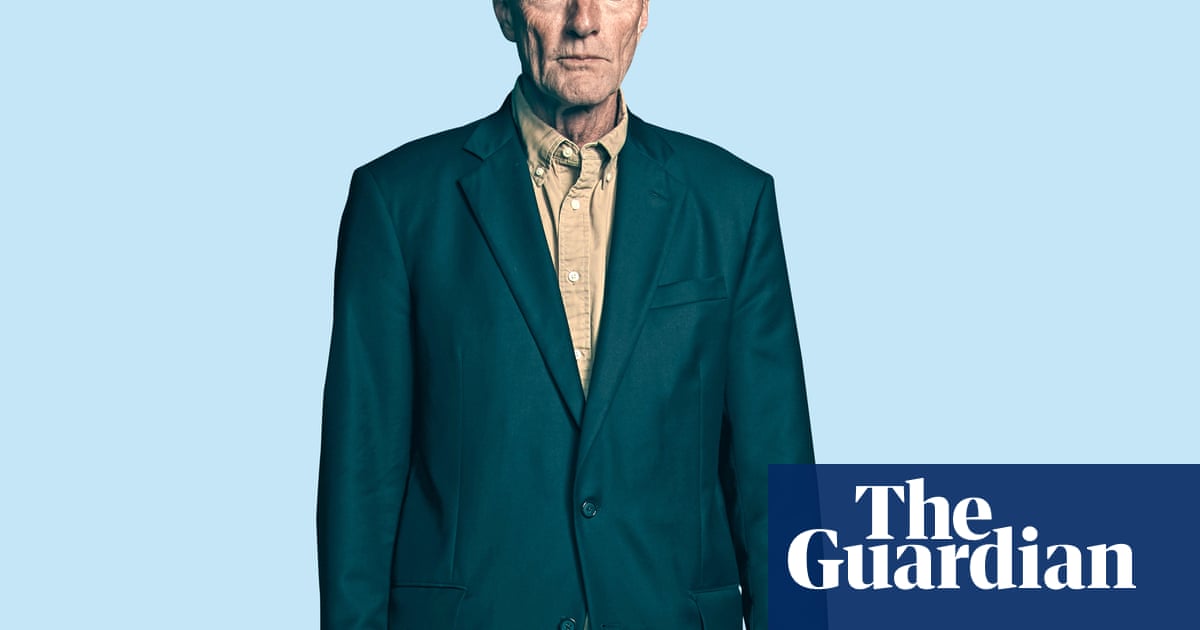

Max du Preez was the founding editor of Vrye Weekblad, an anti-apartheid, Afrikaans weekly newspaper

.png) 2 months ago

39

2 months ago

39