Victor Hugo is the French equivalent of Shakespeare and Dickens. The inventor of Quasimodo and Jean Valjean is so universal that we absorb his myths even if we have never picked up one of his books. Yet how much do most of us know about Hugo himself, behind the books, the films, the musicals? By dedicating an exhibition to this versatile creator’s visual art, which started with a few caricatures and developed into sublime and surreal masterpieces, the Royal Academy does something unexpectedly moving. It takes you into the secret heart of a man we tend to think of only as a classic.

For instance we discover that Hugo campaigned against the death penalty nearly two centuries ago. His 1854 drawing Ecce Lex (Behold the Law) is a macabre inky portrait of a hanged corpse, part of his doomed campaign to save a condemned murderer called John Tapner. Hugo opposed capital punishment on principle, but a few years later gave permission for this drawing to be made into a print protesting the execution of American anti-slavery activist John Brown. If there was a liberal cause, Hugo threw his huge heart into it.

One of the first drawings you encounter in this sensitively curated show is his sketch of the council chamber in the town hall of Thionville in the north-east of France, after it was left in ruins by the invading Prussian army in 1871. Thus, in his late 60s, he added war artist to his vocations of author and campaigner, and recorded the violence of the Franco-Prussian war. In fact, this disaster for France improved his own life. It led to the fall of the dictator Louis Napoleon, whom Hugo had defied, choosing political exile on Guernsey, where he created some of his most haunting art.

That was his public life. Hugo’s art, however, takes you under his skin, without rules or any audience except himself, absolutely free and dauntingly creative. You can feel the isolation and soul-searching in his 1850 sketch Causeway, which dwells on nothing more than a bleak rocky causeway, perhaps his road to exile. In a drawing beside it he ponders the woody morass of a soaking breakwater in Jersey – the first Channel Island to which he fled.

Sketch? Drawing? It’s hard to define exactly what these are. Hugo uses a mixture of ink, charcoal, graphite and wash to create his murky paper visions. Sometimes he works on a tiny scale: The Abandoned Park, a silhouette-like image of trees beside a mirroring lake, is just 4.4cm tall and 3.5cm across. The miniaturisation adds to the ghostliness. Yet he can also take drawing to staggering largeness, as in the final depiction of a Guernsey lighthouse with a frail staircase spiralling up to a mystical, hopeful light.

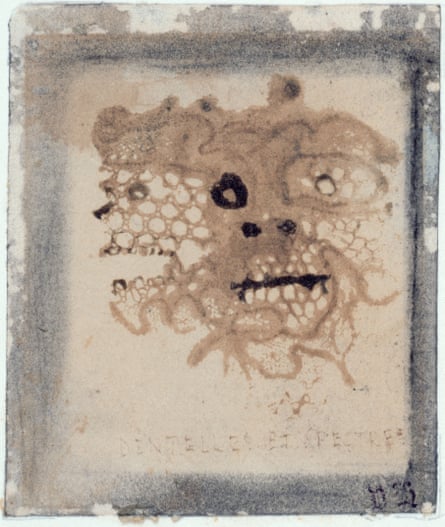

At times Hugo is just the writer doodling – using up spare ink, he said – yet his doodles develop. A symmetrical ink stain, like a Rorschach blot, has little faces drawn into it. Other frolics that Hugo called “taches”, or stains, are boldly abstract. Sometimes they form themselves into cosmic visions of planets or unreal landscapes but others remain free and formless.

Out of this wild freedom a theme emerges: architecture. This should not be a surprise because after all the real hero of his novel Notre-Dame de Paris is not Quasimodo but Notre-Dame itself – a tottering, unloved old pile of stone when Hugo wrote it. So as well as Dickens, he resembles those Victorian champions of the gothic Ruskin and Pugin. But he’s Ruskin on a lot of beaujolais, his imagination drunk on gothic turrets and spires; castles on hilltops or by lakes; fairytale castles and nightmare castles; real ones and dreamed ones.

When he visited the town of Vianden, in today’s Luxembourg, its castle fascinated him so much he lived in it for three months. He depicts it as shadowy and unreal, like a design for a 30s horror movie. In a second drawing the castle is a floating phantasm above a rickety array of wooden houses: not so much Dracula’s castle as Kafka’s.

When Hugo lived on Guernsey he turned his house into a gothic retreat with a Romantic interior full of fantastical touches. It is evoked here with spooky photographs and a battered mirror whose wooden frame he painted with colourful birds. His fireplace, which he sketched, was emblazoned with a huge H, as if he were a medieval lord.

after newsletter promotion

We think of French art in the 19th century as a series of “isms” – Romanticism being defeated by realism giving way to impressionism which inspired post-impressionism. Hugo was a Romantic yet he lived on until 1885, doing the art we see here into old age – and it is timeless, eternally contemporary. Uninterested in artistic fashion – his living came from writing – he followed his own fancy. Like Goya, whom he often resembles, this makes his art speak directly to us.

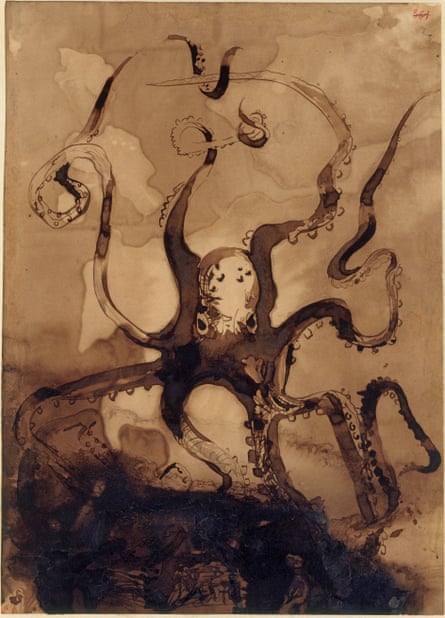

Here is a portrait of an octopus, which he must have seen from the Guernsey rocks, its flailing tentacles making him, and you, wonder if it has a consciousness. Hugo feels the universal pulse of life. He can empathise with medieval outcasts, hanged men and cephalopods. What an artist. What a soul.

-

Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo is at the Royal Academy, London, 21 March to 29 June

.png) 1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31