It was, says Chris Lemons, “very much a normal day at the office”. Until things went wrong. But when they went wrong, they went wrong very badly, very quickly. The “office” was actually the bottom of the North Sea, where Lemons was left without air for almost half an hour.

Lemons was working as a saturation diver, living in a pressurised chamber onboard a specialised ship for stints of up to a month, and being lowered to the seabed in a diving bell to work on offshore structures. “It is a serious business, but it is routine for us. That bell going down is like the taxi to work. I always felt comfortable down there.”

On 18 September 2012, Lemons, along with colleagues Duncan Allcock and Dave Yuasa, took their diving-bell “taxi” to work at a depth of 90 metres (295ft). Allcock, the most experienced of the three and something of a mentor to Lemons, was to stay in the bell while Lemons and Yuasa dropped out in their diving suits to repair a pipe on a manifold, a big yellow drilling structure used by the oil industry, about the size of a house. Saturation divers are attached to the bell with umbilicals, cables that provide them with communication, power and light, as well as a mixture of oxygen and helium to breathe, hot water to keep them warm, and a means to find their route back to the safety of the bell. “Our umbilicals are exactly what they sound like: givers of life,” says Lemons, 45, on a video call from the south of France where he now lives.

The bell in turn was connected to the ship, the dive support vessel Topaz, which had a crew of 120 and was positioned 103km (64 miles) north-east of Aberdeen. The ship held its place over the dive area without an anchor, guided by a “dynamic positioning” computer system.

On that day, the weather was bad – 35 knots of wind and a 5.5-metre (18ft) swell – but not unusual for the North Sea, nor prohibitive to diving. “We don’t really notice that on the bottom,” says Lemons. In fact, though it was dark, visibility wasn’t too bad. “Generally in the North Sea you can’t see much. That is half the battle, being able to orient yourself. But on that occasion, we could see the bell from where we were.”

They had been working for about an hour when things went wrong. There was an open line of communication to the ship and they heard alarms going off. Not unusual, but then came a message from the ship directly to Lemons and Yuasa: “Leave everything there – get out of the structure, boys.”

They dropped off the manifold to the seabed. “That’s when the confusion started,” says Lemons. “Going up to the surface is never an option – you would die from explosive decompression pretty quickly. There is only one safe place: the diving bell.”

But the diving bell, which had been 10 metres (33ft) above them, wasn’t there. The Topaz’s dynamic positioning system had failed and the ship was drifting off in the gale, pulling the bell with it. But the bell was still attached to the other end of their umbilicals, so they began to climb the cables. “I don’t remember processing what was going on. You’re just trying to get back to that safe place, climbing hand over hand, as did Dave next to me.”

But, suddenly, Lemons couldn’t climb any more. A loop of his umbilical had snagged on the manifold they’d been working on. The ship pulled on the bell, which pulled on the umbilical. “I immediately knew it was caught. You’ve got this 8,000-tonne vessel pulling that umbilical tight – there was nothing I could do to release it.”

In fact, because the cable was caught on part of the manifold, Lemons initially found himself being pulled back into it. “I was thrashing around like a fish trying to get out of there, shouting for slack. My next thought was that if it continued to slip, there was a small gap in the structure I was going to get pulled through, like being pulled through a cheese grater. That’s not going to be a nice way to go. The first real dose of luck I had was that it stopped slipping.” It’s a testament to Lemons’s talent for understatement, and the absolutely desperate situation, that he sees this as luck.

Soon, Yuasa noticed that Lemons was in trouble: “He realised there was a problem and turned to get back to me. We couldn’t speak to each other, but I remember our eyes meeting. I’m imploring him to help me, but he’s being dragged away. I lost sight of him, but I could still see his light. Then I lost sight of that.”

Meanwhile, the ship continued to pull on Lemons’s umbilical. He doesn’t remember hearing the cable break; it happened in stages, comms first, “like a jack being pulled from a speaker. I lost all communication, which puts you in a very lonely place. Then [I lost] the hose which provides an infinite amount of gas – suddenly I had nothing to breathe at all.”

Yuasa made it back to the bell, exhausted. On the ship, they desperately tried to get the dynamic positioning system running again. Meanwhile, Lemons did what saturation divers are trained to do. “We carry these emergency supplies. You never expect to have to use them, but when you’ve suddenly got nothing to breathe it’s an instinctual thing to turn the knob on the side of the helmet to open the supply. That puts you in a very different world: the moment that you open that, you’ve moved from a place where you have this infinite supply to one where you very much have a finite one – about eight or nine minutes’ worth.”

When the umbilical broke, Lemons had fallen back on to the seabed. His first task was to find the manifold, which is where a rescue attempt, if there was one, would take place. But that wasn’t easy without a light. “It was the most infinite darkness. I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. It’s easy to get disoriented at the best of times, with a compass and a light and someone telling you where to go. I knew this enormous yellow structure was probably only a couple of metres away, but I had no idea which direction. Again, I was very lucky – I bumped straight into it.”

He climbed up the manifold, fearful of letting go and losing it again, and got to the top. “For some reason, I expected to see Dave on his way back to me, or the diving bell. But when I got there and looked up, there was nothing but the most absolute blackness in the sea above me.”

It was cold, about 3C (37F), and Lemons had lost his hot water supply. “I would have been hypothermically cold very quickly, but I don’t have a memory of that. Maybe your body has an ability to shut out unnecessary information. Or perhaps my memory is not as good as I thought. I feel I’ve got this fairly lucid recollection of everything up to the point where I fall unconscious.”

He reckons that of the eight or nine minutes of gas he had, he’d probably used four or five. “I won’t pretend I wasn’t scared and breathing hard. I realised that even if Dave had been there, the chances of him getting me back to a breathable environment before I ran out of gas were minimal. With nobody there, I decided this was probably going to be it. In a strange way, that had a calming effect; the fear, the panic drained out of me – there was nothing I could do. I assumed a sort of foetal position and was overtaken by grief. A great sadness took over at that point.”

What was he thinking of in that moment? “I was at an exciting point in my life: early 30s, getting married the following year, we were in the process of building a house … I had all the hopes and dreams you have at that stage – of children, travel – and it felt as if all of that was about to be ripped away in this strange, lonely, ethereal place. I grew up in a middle-class family on the outskirts of Cambridge, and I remember thinking: ‘How is this dark, lonely place where I end my days?’”

He also tells me he was worried what they were going to find on his mobile phone, but then says he’s joking. Lemons is very funny – that doesn’t come across in the documentary that was made about his accident.

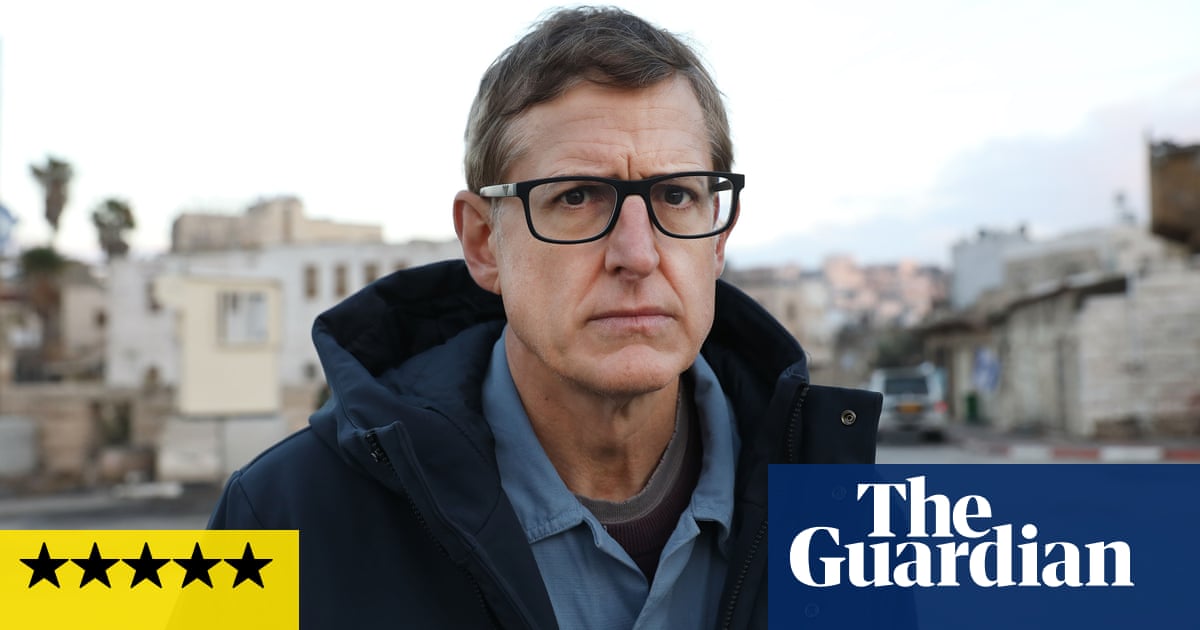

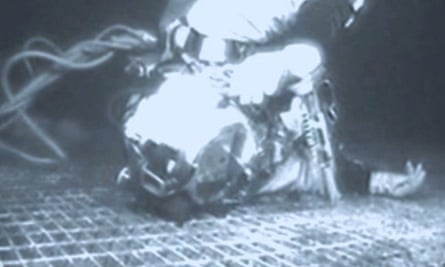

In the 2019 documentary Last Breath, interviews with Lemons, Yuasa, Allcock and others are interwoven with footage from the day and some reconstructed scenes. The most powerful, haunting footage is taken from a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), like a mini, unmanned submarine, which was launched from the Topaz. Lemons is lying on top of the structure, in the foetal position, and his arm is moving, twitching. Some of the ship’s crew take it to be a sign that he’s waving at the ROV, letting them know he’s still alive and they need to get a move on. Today, Lemons dismisses this. “I’m definitely unconscious at the point where the ROV finds me. We’ve got a few theories as to what that was.” To put it another way: he was not waving but drowning.

He doesn’t remember the moment he lost consciousness. He thinks it was the carbon dioxide that put him under, and that’s why the “actual moment was peaceful. I feel like a bit of a charlatan. I still get contacted all the time by people who’ve lost loved ones, but I don’t have the right to tell you what it’s like – I didn’t die.”

Somehow, they got the dynamic positioning system going again and relocated the manifold. Allcock and Yuasa were still in the bell. Yuasa left the bell again to get Lemons, presumably expecting to bring back a body. It had been 35 minutes since his umbilical snapped, and Lemons had just eight or nine minutes of emergency gas.

They dragged him back into the bell and took off his helmet. He was bright blue. Allcock gave him mouth-to-mouth, a couple of big puffs … and miraculously, he came round. Lemons doesn’t remember it, but there’s a lovely moment of footage where Yuasa reaches out and holds Lemons, who reaches out and grabs on to him and Allcock. “They’re the real heroes in this story,” Lemons says, “and everyone on the boat. I’m just a damsel in distress.”

How Lemons survived – and without brain damage – for more than 25 minutes is something of a mystery. He has been to medical conferences and spoken to many experts in his search for answers, but the professionals are as perplexed as he is. He thought it was the cold that had saved him, since there are stories of people falling through ice and surviving for a long time. “But I’ve learned that if my body had been so cold that I’d gone into some kind of hibernation or stasis, there is no way Duncan would have been able to resuscitate me that quickly.”

He still thinks the cold was a factor. And that, because of the pressure, his tissue was saturated with oxygen. He’s also been told that a buildup of CO2 in the blood – hypercapnia – can be neurologically protective. If medical tests had been performed on him immediately after he was rescued, he might have the empirical data that could provide answers; but he had to remain locked away in a pressurised chamber after he arrived back in Aberdeen.

Somehow, he was fine afterwards – physically and mentally. And three weeks, later he was saturation diving again, back on the seabed in exactly the same spot.

Lemons and his fiancee got married and finished building their house. They’re no longer together but he has a new partner, and two kids – the hopes and dreams he had weren’t lost at the bottom of the North Sea. The enormity of what he had been through took a while to sink in. It has given him a more acute awareness of mortality, and of the preciousness and fragility of life. But it’s also underlined the power of human resilience. “We sometimes underestimate what we’re capable of. It’s given me courage and confidence, rather than knocked it out of me.”

Lemons still works in the industry, but as a diving supervisor on the ship, not on the seabed. He is also dialling down the day job and doing more public speaking. It’s funny that by knocking so loudly on death’s door, he has ended up opening a load of others.

And now his story’s being told in a thriller, also called Last Breath, directed by Alex Parkinson. Allcock, from Chesterfield, is played by Woody Harrelson, from Texas. Simu Liu, who played one of the Kens in the Barbie movie, plays Yuasa. And Lemons? Finn Cole, from Peaky Blinders. “Lush head of hair, good-looking lad – makes complete sense,” says Lemons, who is – and was at the time – bald.

Right, the taxi’s waiting. He’s got to go to the airport. A proper taxi, on dry land. Lemons, Allcock and Yuasa are off to New York, for the premiere of Last Breath.

.png) 1 month ago

13

1 month ago

13