During my 20s, I was too poor to go abroad on holidays, as my friends did. They would go somewhere blazingly hot, and roast themselves stupid on beaches filthy with cigarette ends and beer cans. I was a landscape gardener, and my summers were spent in the Surrey Hills, building walls and terraces from stone. By the time I reached my 30s, however, I had a girlfriend – and, because I had become a teacher, a few weeks’ holiday in the summer.

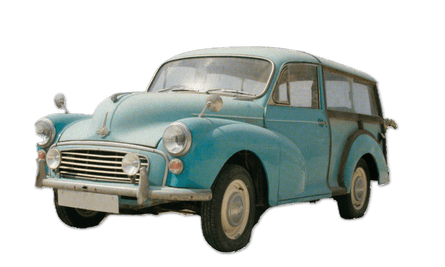

Annie was from Northern Ireland, and she taught French. During half-terms and the shorter holidays, we would go to Donegal to escape the stress and horror of the Troubles. But in the summer we would pile into my home-made Morris Minor Traveller, built out of two wrecks, and cross the Channel to France. We would drive from one historic town to another, pitching our tiny camouflaged tent in the municipal campings, where the French would set up capacious awnings and drink cold white wine in folding chairs with their dignified, amused cats sitting beside them like statues of Bast.

Quite often, Annie and I would do le camping sauvage, which was technically illegal, but in fact nobody gave a damn. Farmers would turn up for a conversation, and even bring croissants. One day I woke up with my chest covered in ticks, and Annie sizzled them off with a cigarette. In army mess tins, we cooked up petit pois in butter and mushrooms in garlic. For lunch it was grapes, brie and baguette.

The Morris made us popular. The French love a good teuf-teuf. I have a picture of it in Caen with the bonnet up, and several Frenchmen inspecting the engine. Once, I was overtaken and flagged down by two sheepish gendarmes. When I asked why they had stopped me, one of them gestured at the car and said simply: “Elle est belle.”

One day we went to see Bernières-sur-Mer, the town on the Normandy coast where my ancestors were once feudal lords. Afterwards, we drove inland to find somewhere to camp and roast a chicken. Outside one of the villages, I spotted a track into some woodlands. Morris Minors are tough, so we bumped along it through the low arch of trees. The track curved at 90 degrees and suddenly stopped in a tiny grassy clearing, where there was a spring and a ring of charred stones. When I looked into the spring, it was teeming with fresh water shrimps. The water was earthy and clean.

I had the strongest feeling of having come to a sacred place where I felt completely happy, and completely at home. I think that Annie felt its magic, too.

Over the years I stayed there many times, either accompanied or alone. It was my place in Normandy. I often wondered if any of my ancestors had ever lingered there.

The last time I went there I was returning from Toulouse, having taken a friend home after her year of being a teaching assistant. I adored her but she was not attracted to me, and those last few days with her were painful, so I cut short my stay in Toulouse and drove back to Normandy. I stayed by the little spring for three days, grieving and reflecting, reading Colette, and writing notes for poems and songs. Any longer and it would have become difficult to leave. In those few days I caught a glimpse of the deep peace of an eremitic life.

But one year my new girlfriend, Caroline, said: “Please can we not go to France and drive around in your Morris Minor any more?”. I said: “You choose something, then.” She chose Cephalonia, and the result was Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. For the next summer she chose south-west Turkey, and so I came to write my best novel, Birds Without Wings. She entirely and unwittingly changed the course of my life.

Greece and Turkey became other spiritual “homes”, but France is literally and metaphorically in my veins. I like to think that one day in summer I will load my Morris Traveller with camping gear and fishing tackle, and go to live, for a few last days, by that circle of charred stones, next to the spring that teems with shrimps, and is so reverberant with memories.

-

Louis de Bernières’s fourth novel, Captain Corelli’s Mandolin became a worldwide bestseller in 1994

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

.png) 3 months ago

60

3 months ago

60