A warning at the outset – the birth of modernism, in Brasil! Brasil! at the Royal Academy, does not mean the actual baby. You will not be flying down to Rio in the 60s. There will be no cool constructions by Lygia Pape or fluttering sculptures by Hélio Oiticica, no hint of Oscar Niemeyer’s sweeping architecture and certainly no suave bossa nova soundtrack by João Gilberto.

You may not even recognise a single name. Which is entirely the point: to introduce us to the early avant garde of a nation convulsed by dictatorships and coups. In the approximate timespan of this show – from the general strike in 1917 for the most basic of labour rights for workers in factories and fields to the military coup of 1964 – art is confined, sidelined, often political. And most of it stayed where it was made, in Brazil.

But a fraction got out, and was shown at the Royal Academy in the wartime winter of 1944, bringing what the Daily Telegraph at the time called “an exotic richness to the walls of Burlington House”. Perhaps this refers to the bright green palm trees and hot pink favelas of artists such as Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973), dotted with dark-skinned labourers, which account for barely a painting or two in the present show. Much is made of this historical connection in the foyer and the catalogue – Brazilian artists donated their work for sale on behalf of the RAF Benevolent Fund – and perhaps it is no wonder. For how else to explain this lavish exhibition of bafflingly weak art, co-presented with the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, if it is not another kind of diplomatic initiative?

Ten artists are given a gallery each. Clear and concise, or so you might think, but straight away there is a confusion. The opening gallery is a radiant sunshine yellow that overwhelms the small canvases in rough paint – mainly mouse brown and grey – by the first artist, Lasar Segall (1889-1957). A Lithuanian Jew who lived and worked in Vilnius, Dresden and Berlin before taking Brazilian citizenship in his mid-30s, Segall produced work that goes in drastically different directions.

Pogrom presents a desperate heap of corpses, a tiny dove of peace hovering above, scrolls of the Torah crushed below. Painted in 1937, it recalls Lithuania’s past even as it predicts the future. Whereas his 1927 painting of a mixed-race worker on a banana plantation tries to put the African art back into cubism with a totem head and chopped palm leaves. It is terrible.

Segall’s work is so variously derivative that you might be looking at half a dozen painters, and so it goes for quite some way. Brazilian artists from affluent backgrounds made the trip in reverse, leaving for long stays in Paris and Berlin and trying out the expressionism, cubism, futurism and fauvism that lie, often entirely undigested, in their works.

For this shocking Euro radicalism, in a 1917 exhibition in São Paulo, Anita Malfatti (1889-1964) was so harshly criticised by the Brazilian press that she left off showing altogether. And this question of what is, or should be, the look of Brazilian art runs through this exhibition even now.

Do Amaral’s most famous painting, Abaporu, showing the gigantic foot of a tubular nude pressed up against a cactus, is not here. But her fusions of European movements with Afro-Brazilian culture in any case fade away, alas, after the 1930 revolution. She goes to Moscow, joins the Communist party and produces some woeful agitprop. Second Class (1933) shows barefoot Brazilians as mawkish puppets with uniform faces, adult and child exactly alike. I am sorry I saw this painting.

The curators tie themselves in knots with upper-class artists, trained in Paris, returning home to appropriate themes and motifs from Afro-Brazilian culture “despite having no direct contact with Brazil’s Indigenous population”. And their wall texts can be strangely unhelpful. You would not know that Candido Portinari (1903-62) – arguably Brazil’s national artist during these decades – was not just a painter of heroic coffee workers and enormous murals of rural labourers, but of religious art too. Or that he left more than 5,000 works when he died of lead poisoning from his own oil paints at the age of 58.

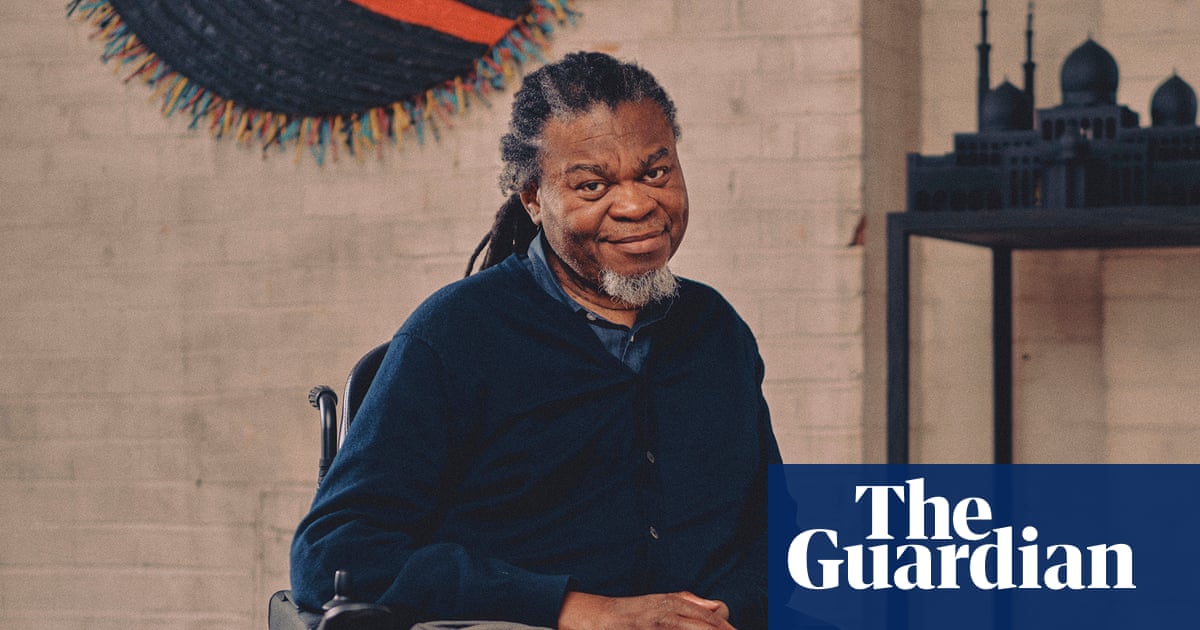

Alfredo Volpi (1896-1988) and Djanira da Motta e Silva (1914-79) belong to the cultures from which they paint, in scenes of village festivals, kite-flying children, town facades and favelas. Rubem Valentim (1922-91), a wonderful discovery here, integrates into his ultra-sharp geometric paintings and gleaming wooden constructions all sorts of symbols – arrows, circles, triangles and hatchets – from the local Candomblé religion. Sometimes he combines painting and sculpture in the most original way, setting up receding shadows, and his colour is both hot and cool. He started out life as a dentist.

Valentim is so much better than all the other self-taught artists in this show that it is hard to know how the cast list was conceived in the first place. Or indeed what anyone is supposed to discover about Brazilian art from such a weird mishmash of weakly adapted pastiches of European modernism, crude socialist realism and sudden flares of originality. The show’s spectacular design, by the Brazilian architect Carla Juaçaba – radiant LED lights glowing around picture frames, fabulous colour shifts for walls and geometric furnishings with each gallery – can’t help upstaging the art.

Visitors will learn a lot, however, about manifestos and groupings, one-off performances and significant exhibitions, about the Semana de Arte Moderna that took place in São Paulo in 1922, backed by a coffee oligarch and featuring some of these painters. But reading and seeing are hardly the same thing. It sometimes feels as if this show, which ends exactly at the point where it ought to start, is being driven not by art so much as art history.

-

Brasil! Brasil! The Birth of Modernism is at the Royal Academy, London, until 21 April

.png) 2 months ago

31

2 months ago

31