Do people from different cultures and environments see the world differently? Two recent studies have different takes on this decades-long controversy. The answer might be more complicated, and more interesting, than either study suggests.

One study, led by Ivan Kroupin at the London School of Economics, asked how people from different cultures perceived a visual illusion known as the Coffer illusion. They discovered that people in the UK and US saw it mainly in one way, as comprising rectangles – while people from rural communities in Namibia typically saw it another way: as containing circles.

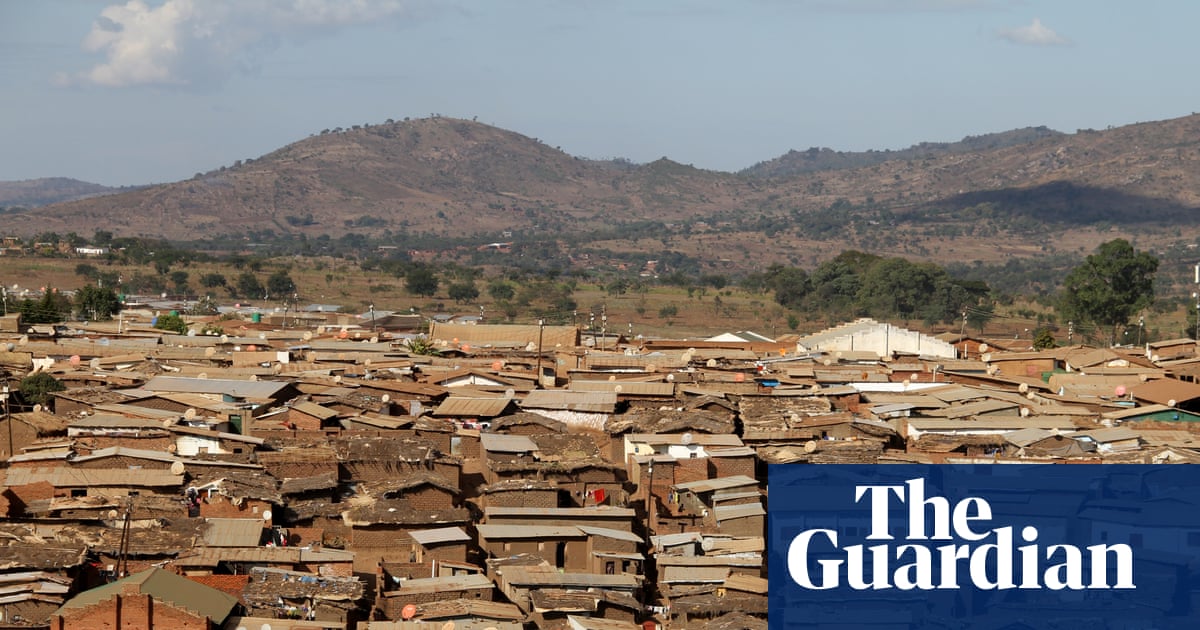

To explain these differences, Kroupin and colleagues appeal to a hypothesis raised more than 60 years ago and argued about ever since. The idea is that people in western industrialised countries (these days known by the acronym “weird” – for western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic – a summary that is increasingly questionable) see things in a specific way because they are generally exposed to highly “carpentered” environments, with lots of straight lines, right angles – visual features common in western architecture. By contrast, people from non-“weird” societies – like those in rural Namibia – inhabit environments with fewer sharp lines and angular geometric forms, so their visual abilities will be tuned differently.

The study argues that the tendency of rural Namibians to see circles rather than rectangles in the Coffer illusion is due to their environments being dominated by structures such as round huts instead of angular environments. They back up this conclusion with similar results from several other visual illusions, all supposedly tapping into basic brain mechanisms involved in visual perception. So far, so good for the cross-cultural perceptual psychologists, and for the “carpentered world” hypothesis.

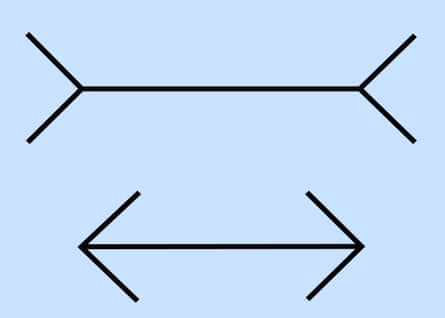

The second study, by Dorsa Amir and Chaz Firestone, takes a sledgehammer to this hypothesis, but for the much better-known illusion: the Müller-Lyer illusion. Two lines of equal length seem to be different lengths because of the context provided by inward-pointing, compared with outward-pointing, arrowheads. It’s a very powerful illusion. I’ve seen it on thousands of occasions and it works every time for me.

There are many explanations for why the Müller-Lyer illusion is so effective. One of the more popular is that the arrowheads are interpreted by the brain as cues about three-dimensional depth, so our brains implicitly interpret the illusion as representing an object of some kind, with right angles and straight lines. This explanation fits neatly with the “carpentered world” hypothesis – and indeed a lot of early support for this hypothesis relied on apparent cultural variability in how the Müller-Lyer illusion is perceived.

In their study, Amir and Firestone carefully and convincingly dismantle this explanation. They point out that non-human animals experience the illusion, as shown in a range of studies in which animals (including guppies, pigeons and bearded dragons) are trained to prefer the longer of two lines, and then presented with the Müller-Lyer image. They show that it works without straight lines, and for touch as well as vision. They note that it even works for people who until recently have been blind, referencing an astonishing experiment in which nine children, blind from birth because of dense cataracts, were shown the illusion immediately after the cataracts were surgically removed. Not only had these children not seen highly carpentered environments – they hadn’t seen anything at all. After you absorb their analysis, it’s pretty clear that the Müller-Lyer illusion is not due to culturally specific exposure to carpentry.

Why the discrepancy? There are several possibilities. Perhaps there are reasons why cross-cultural variability should be expected for the Coffer but not the Müller-Lyer illusion (one possibility here is that the Coffer illusion is based on how people pay attention to things, rather than on some more basic aspect of perception). It could also be that there are systematic differences in perception between cultures, but that the “carpentered world” hypothesis is not the correct explanation. It’s also worth noting that the Kroupin study has some potential weaknesses. For example, the UK/US and Namibian participants were exposed to the illusions using very different methods. All in all, the jury remains out and – favourite scientist punt coming up – “more research is needed”.

The notion that people from different cultures vary in how they experience things is certainly plausible. There’s a wealth of evidence that as we grow up our brains are shaped, at least to some extent, by features of our environments. And just as we all differ in our externally visible characteristics – height, body shape and so on – we will all differ on the inside too. As the author Anaïs Nin put it in quoting the Talmud: “We do not see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

For me, an important implication of this line of thought is that there are likely to be substantial differences in perception within “groups” as well as between them. This will probably hold however these “groups” are defined, whether as different cultures or as a contrast between “neurotypical” and “neurodivergent” people. I believe that paying more attention to within-group perceptual diversity will help us to better interpret the differences we do find between groups, and equip us with the tools needed to resist relying on simple cultural stereotypes as explanations.

More research is needed here too. But it’s on the way. In the Perception Census, a project led by my research group at the University of Sussex together with professor Fiona Macpherson at the University of Glasgow, we are studying how perception differs in a large sample of about 40,000 people from more than 100 countries.

Our experiment includes not just one or two visual illusions but more than 50 different experiments probing many different aspects of perception. When we’re done analysing the data, we hope to deliver a uniquely detailed picture of how people experience their world, both within and between cultures. We’ll also make the data openly available for other researchers to explore new ideas in this important area.

One critical insight lies behind all these questions. How things seem is not how they are.

For each of us, it might seem as though we see the world exactly as it is; as if our senses are transparent windows through with the world pours itself directly into our mind. But how things are is very different. The objective world no doubt exists, but the world we experience is always an active construction, a kind of “controlled hallucination” in which the brain uses sensory signals to update and calibrate its best interpretation of what’s going on. What we experience is this interpretation, not a “readout” of the sensory information.

For me, this is the key insight that underlies any claim about perceptual diversity. When we take it fully on board, it encourages a much-needed humility about our own ways of seeing. We live in perceptual echo chambers, just as we do in those of social media, and the first step to escaping any echo chamber is to realise that you’re in one.

-

Anil Seth is a professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience at the University of Sussex, and author of the Sunday Times bestseller Being You: A New Science of Consciousness

.png) 2 months ago

42

2 months ago

42