A cremation pyre built about 9,500 years ago has been discovered in Africa, offering a fresh glimpse into the complexity of ancient hunter-gatherer communities.

Researchers say the pyre, discovered in a rock shelter at the foot of Mount Hora in northern Malawi, is thought to be the oldest in the world to contain adult remains, the oldest confirmed intentional cremation in Africa, and the first pyre to be associated with African hunter-gatherers.

In total 170 individual human bone fragments – apparently from an adult woman just under 1.5 metres (5ft) tall – were discovered in two clusters during excavations in 2017 and 2018, with layers of ash, charcoal and sediment.

However, the woman’s skull was missing, while cut marks suggest some bones were separated at the joints, and flesh was removed, before the body was burned.

“There is no evidence to suggest that they were doing any kind of violent act or cannibalism to the remains,” said Dr Jessica Cerezo-Román of the University of Oklahoma, who led the study. Instead, she said, body parts might have been removed as part of a funerary ritual, perhaps to be carried as tokens.

Dr Jessica Thompson, a senior author of the study from Yale University, said that, while such practices may not seem relatable, people still keep locks of hair or relatives’ ashes for scattering in a meaningful place.

The researchers said the rock shelter appears to have been used as a natural monument, with burials occurring from about 16,000 to 8,000 years ago. As well as complete skeletons, very small collections of bones from different individuals have been found.

“[This] supports our hypothesis that some of the missing bones from the cremated woman may have been deliberately removed and taken as tokens for curation or reburial elsewhere,” said Dr Ebeth Sawchuk, a co-author of the study from the University of Alberta.

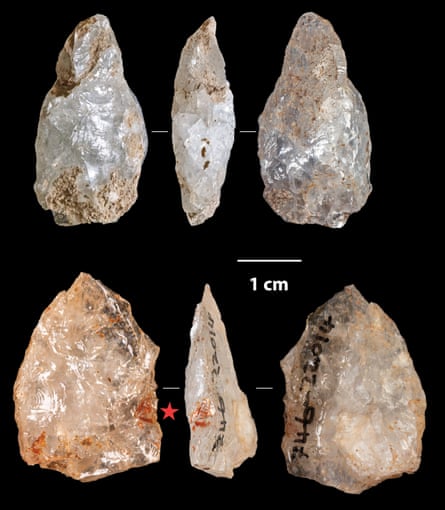

The team also found flakes and points from stone-knapping within the pyre, which might have been added as part of a funeral ritual.

“Were people actively throwing these things into the fire or … were they in the body itself?” said Thompson. Cerezo-Román said one possibility is that people were knapping stones to cut the woman’s flesh.

The team also found the pyre was about the size of a queen-sized mattress, and would have taken considerable knowledge, skill and coordination to build and maintain, while the two clusters of bones indicate the body was moved during cremation.

While it is unclear why the woman was given such special treatment, the team found at least one fire was subsequently made directly above the location of the pyre – possibly as an act of remembrance.

However, the site also has evidence of multiple campfires, with Thompson noting it is likely the shelter would also have been used for daily life.

Writing in the journal Science Advances, the team note the oldest known pyre containing human remains was previously found in Alaska, and dates to about 11,500 years ago – however, that was for a young child.

Indeed, most burned human remains dating back 8,000 years or more have not been found in a pyre, and prior to the latest find the earliest confirmed intentional cremations in Africa only appeared about 3,500 years ago, among pastoral Neolithic people.

Thompson said the discovery that different people merited different treatment in death “suggests that in life, they also would have had a lot more complexity to their social roles than I ever imagined, or that certainly is stereotypically described for tropical hunter-gatherers, especially this old”.

Joel Irish, a professor of anthropology and archaeology at Liverpool John Moores University, who was not involved in the work, welcomed the discovery.

“That it is such an early date, and that they would have been transient as hunter-gatherers makes it more amazing,” he said.

“They clearly had advanced belief systems and a high level of social complexity at this early date.”

.png) 1 month ago

23

1 month ago

23