It happens every few years. An artistic director leaves a theatre; another steps up or down or sideways to take the position; a third follows. Within months a sweeping change has occurred and the theatrical landscape looks entirely different.

After the last spin of the wheel in 2019 the crucial changes were immediately evident. They marked the beginning of the end of a particular hegemony: that of the white British male. This time the alterations are inspiriting in a different way. The talent and the zeal, the raring-to-go of the directors taking up new positions, have survived one of the bleakest of arts eras. In lockdown the stage was shredded: the National Theatre in London was wrapped up in barrier tape saying “Missing Live Theatre”; freelance performers, designers and directors were stripped of all income, often forced to leave their professions. In the social distancing that followed, auditoriums looked like crime scenes, with seats sealed off.

Meanwhile the arts have slipped off the school curriculum: treated as merely decorative; assumed in the case of theatre to be the domain of kids who go to fee-paying schools equipped with their own stages. When the actor Michael Sheen launched – and funded – the Welsh National Theatre last month, he talked of a “climate of fear” surrounding funding in the country.

Sheen took Laurence Olivier, founder of the National Theatre, as his figurehead. In 2009 another inspirational head of that theatre, Richard Eyre, gave a wonderful account of what it is to be an artistic director in his book National Service. Eyre detailed the thrilling, onerous components of the job – the programming, the fundraising, the rows, the bombardment from performers, audiences, writers, designers, engineers – and the emotional toll and excitement the post entails. He did not offer a prescription for success. There is no such thing, any more than there is for a sellout show: who would have predicted that Oedipus would have people fighting for tickets last year?

Vitality is in difference and independence: it can be fuelled by responding to a particular place and time, or by conjuring up an imaginative, wide-ranging project. It is invigorating to hear Elizabeth Newman’s very particular plans for Sheffield Theatres, which continue the tradition – seen most recently in Standing at the Sky’s Edge – of responding to the city. Actor Alan Cumming, who has just taken over as the self-styled “Pied Piper of Pitlochry”, has yet to announce his programming at the Highland theatre, but is also looking to give it both local roots and a long reach.

Equally, David Byrne’s more general plan for the Royal Court – Starmer-like in its long-termism – has the authoritative sound of a carefully considered vision. And I am betting that Indhu Rubasingham – the woman behind both The Wife of Willesden and The Father and the Assassin – will make the National Theatre’s three stages distinctive, not allow them to be scaled-down versions of each other: the National is best when, like London, it is a series of interlinked settlements with separate identities. I hope Rubasingham also puts some Kiln-like fire into the cafes.

One show may put a theatre on the map – look what Operation Mincemeat did for Byrne at the New Diorama. Yet an artistic director must provide a glimmer of expectation that persists, surrounding a theatre even after a less buoyant – or rotten – production. The Almeida has had that glimmer under Rupert Goold, who next year takes over the Old Vic. He has generated a sense of necessity – the equivalent of building a library – that is not dependent on any one claim to authority (new writing, musicals, visual flair) but which continually trips you up with surprise: you have to keep attending.

The emphasis on ticket prices here is right. It is not only that ridiculously high charges keep people out. Unless audiences feel able to be more casual about theatregoing and take a chance on a new play, new plays will not be programmed. There are other barriers that artistic directors need to bash down. Historically one of these has been the buildings themselves: crossing the threshold has often been like entering sacred ground – and then like being kettled. That is slowly changing: at the redesigned National and at the Bridge (both taken in hand by the firm of Haworth Tompkins), spectators are eased from exterior to interior. The West End – and Old Vic – might take note.

Meanwhile: let’s also have some bans. On putting versions of movies on to the stage. On jetting in celebrities to suck the energy out of a production. When Sheen was asked if he would be approaching Catherine Zeta-Jones and other Welsh exiles to act in his theatre, he said they would face stiff competition from actors who actually lived in Wales. Hwre! Susannah Clapp

Indhu Rubasingham: ‘Every audience likes a good story, well told’

National Theatre, London SE1; takes up her new post on 1 April

“It’s a little mad, but it’s OK,” laughs Indhu Rubasingham, who is still coming to terms with landing the top job in British theatre.

It was announced in December 2023 that she would be taking over as artistic director at the National – the first woman and person of colour to be appointed to the role. Previously, Rubasingham was at the Kiln theatre in north London, where, in 11 and a half years, she oversaw a major renovation and rebrand while delivering crossover hits such as Red Velvet and The Father. The biggest difference in her new job – she takes over officially from Rufus Norris in April but has spent the past eight months prepping for it – is scale. “There are about 900 full-time staff and over 1,500 freelancers at the National, compared to a staff of 35 to 40 [at the Kiln],” she says. “But the principles are basically the same.”

Rubasingham, 54, grew up in the East Midlands and dreamed of becoming a doctor before falling for theatre in her mid-teens (“I like diagnosing,” she says). She did a drama degree at Hull and made a splash as a director in her 20s, but for a long time felt “utterly intimidated” in a predominantly white industry. Taking charge of an institution was another “really big leap”, and the biggest lesson she took from it was building “resilience at every level: how you keep going, how you programme, how you deal with critics, how you deal with your staff, how you lead… Every moment has been a learning curve.”

She’s keeping the details of her vision for the National under wraps until March, but mainly, she says, “it’s to try and appeal to as many people as possible. Audiences like a good story, well told, and that’s true whether you’re at the Kiln or the National.”

Who or what first got you into theatre?

I did work experience at Nottingham Playhouse when I was 16 and that ignited the bug, being backstage and getting obsessed with it. The same year, I saw The Normal Heart by Larry Kramer. It was the first contemporary play I’d been taken to see. I didn’t realise theatre could be so relevant and in the moment. The political was really emotional – that was the jolt.

Dream person to work with – dead or alive?

Alive, Viola Davis, because she’s a powerhouse and has theatre in her bones. I’d love to see her rip up the National Theatre stage. And the person who’s passed away would be [Malian-Burkinabé actor] Sotigui Kouyaté. He was one of Peter Brook’s actors, an amazing presence.

What’s the hardest part of your job?

Finding enough time.

What can’t you live without at work?

Comfortable shoes. There’s a lot of walking to be done at the National. I had boots on yesterday and my feet were knackered! Everyone is telling me to look after myself, to not get burned out. I’m still trying to work out how. I could give you an answer – regular massages, peppermint tea instead of caffeine – but it wouldn’t be true.

David Byrne: ‘Anything is possible if you plan enough for it’

Royal Court, London SW1; in the job since January 2024

“I see this as a 10-year project,” David Byrne says of his new job at the Royal Court, adding, with no small degree of ambition: “I see it as 10 years to fundamentally change the culture of playwriting in this country.”

Byrne, 41, took over from Vicky Featherstone last January, leaving behind New Diorama, the theatre he founded 10 years earlier. His tenure there, in a small building near Regent’s Park, was distinguished by a risk-taking approach and several successful transfers, including Operation Mincemeat. “We also did a big lockdown project where we built 25 rehearsal rooms in the City and gave them away free for a year,” says Byrne. At New Diorama, he learned “that anything is possible if you plan enough for it, with the right team behind you – and I think I brought some of that energy with me here”.

His first year at the Royal Court backs him up. He began with an adaptation of Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, making extensive use of screens and live cameras, and struck gold with Mark Rosenblatt’s Giant, starring John Lithgow as Roald Dahl, which tackled antisemitism and transfers to the West End in April. His team launched an initiative called the Writers’ Card “to bring together the playwriting community to work out how we best support writers”, and has speeded up the response time for open submissions. “There is [an unsolicited] script sitting on my desk as we talk. We had the writer in last week who was absolutely stunned to hear from us.”

When he speaks about transforming the UK’s playwriting culture, Byrne acknowledges that “people might think I’m going power mad. But ultimately, we are at risk of a very censorious artistic culture where writers feel unable to take risks and theatres are afraid of taking those bigger swings. And I think, historically, when the Royal Court has been brave, it has made the entire culture braver.”

What three words sum up your theatre?

Provocative, contemporary and dissonant.

What are the top three skills you need as an artistic director?

Open-heartedness: the worst thing in theatre is to come across as hard to please – you’ve got to want to celebrate the work of others. Curiosity: you’ve got to be always wanting to find the new, and always interested in what’s coming up in the culture. And the ability to create space: in a time of polarisation, where there are a lot of conflicting views, you’ve got to be able to allow space for equilibrium and for working together.

Dream person to work with – dead or alive?

I’ve been reading about Lilian Baylis, who was at the Old Vic and who, among her eccentric behaviour, used to cook sausages in an oven she put into the wings… I was thinking: however irritating I must be sometimes, at least I’ve never sprayed fat on the props table. So I think she’d have been quite fun to work with, if only to get my eccentricities in context.

What can’t you live without at work?

I’ve eaten a huge amount of fruit pastilles this year. I don’t know why. I don’t drink, really, and I don’t smoke or do drugs. But I’ve had a real hunger for fruit pastilles. I think it’s partly about stress relief. (I say I don’t drink: I have actually started drinking since taking up this job.)

Sell theatre to someone who says they’re not the theatregoing type.

I think it’s OK not to enjoy going to the theatre. I come from a family who don’t enjoy it, and me working in theatre has not convinced them otherwise. I think it is fundamentally part of the human experience, coming together to experience stuff, but I don’t necessarily think it’s for everybody, and that’s all right. There are other forms of culture which are equally enriching.

Are ticket prices too high?

I think it depends on which ticket prices. At the Court we’re still very cheap. Over half of our tickets downstairs last year were £22.50 or lower – that’s really affordable – but obviously elsewhere they are more expensive. I still think there are affordable tickets out there for people wanting to go and see shows.

Elizabeth Newman: ‘It’s like being a vicar. I’m in service to this city’

Sheffield Theatres; in post since December 2024

Elizabeth Newman has only just moved to Sheffield when we speak and hasn’t yet started her new job at Sheffield Theatres, but already she’s fizzing with ideas. Within minutes, the 38-year-old is brainstorming a play about an ice-creamery she has just visited, and another about the city’s workers banding together to set up Sheffield University. “For me, being an artistic director is being a public servant, or a vicar,” she says. “I’m in service to this city. It’s about how we share its story with the world.”

For the previous six and a half years, Newman was in charge of the Pitlochry Festival theatre, where she was known for her community engagement as well as the work she brought to the stage – including her own award-winning production of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer. Before that, she was artistic director of Bolton’s Octagon theatre, and over her career she has directed more than 100 productions around the UK. It’s all the more impressive given that, aged 13 and growing up in Croydon, she developed a neurological condition that left her unable to move from the neck down. She gave up her dream of becoming a ballet dancer and switched to directing, training at Rose Bruford College while relearning how to walk.

At Sheffield Theatres – which comprises the Playhouse, the Crucible, the Lyceum and now the Montgomery – Newman wants to create a supportive environment so that actors and others can be free to take risks. She acknowledges how difficult the climate is for UK theatres at the moment but says that it’s an artistic director’s job to weather it. “That is the job – you face the challenge,” she says.

“It’s a bit like learning how to walk again. You can either sit down and go ‘Oh, well, I’ve been told it’s not possible.’ Or you can go ‘I’m going to give it a bloody good try, and use all of myself to do it.’ Our role as artistic directors is to have vision, to lead the vision, to inspire people to achieve things that they never thought were possible.”

What are the top three skills you need as an artistic director?

Empathy, the ability to hold many things at once, and a deep love of place and people.

What’s your favourite theatre in the world (not your own)?

The National Theatre. It serves the nation, because it’s new and old. I decided I wanted to be a director for two reasons. The first was seeing Angels in America on the telly, which changed my life. The other thing was, at 17, school took us to see the revival of Simon McBurney’s Measure for Measure at the National, and three people made a helicopter land on stage just by moving their arms and bodies. I was just thinking, this is amazing, and it was mixed together with the most beautiful language and extraordinary acting. After that, the National became the place that I felt really welcome because of what Nick Hytner did with the Travelex £10 tickets, so I could afford to go as I got older. I saw all these amazing things that I could only dream of.

What can’t you live without at work?

Diet Coke and a bag of salt and vinegar crisps.

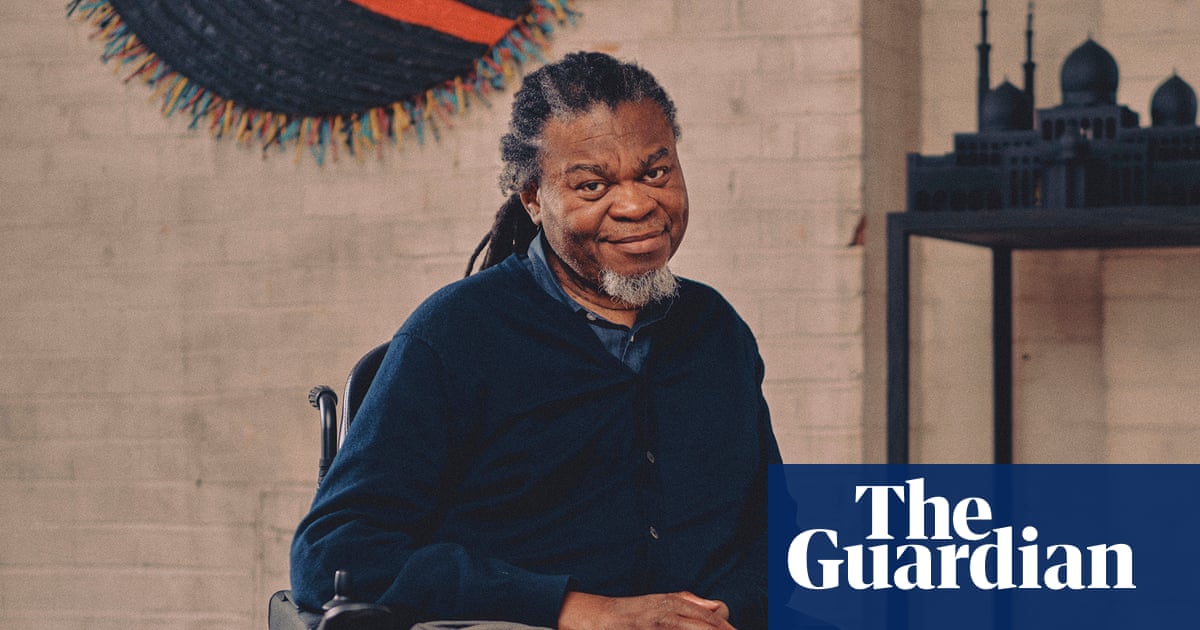

Amit Sharma: ‘We can’t shy away from the political issues we’re facing’

The Kiln, London NW6; in post since December 2023

For Amit Sharma, a key part of his job as artistic director of the Kiln, which he took over in December 2023 from Indhu Rubasingham, is embracing complexity. “The best type of theatre isn’t saying ‘We’re in this one camp’. Actually, it’s exploring all the camps,” he says. “We’re living in such a complex world and we can’t shy away from all the political issues we’re facing.”

Sharma, who was previously the Kiln’s associate director, is also acutely aware of his audiences and their needs. “We serve a local community,” he says. “The current audience is really diverse, it’s reflective of London and the international flavour of people that live here, and our ticket prices have to reflect the local audiences – and through community engagement we’re trying to bring in that next generation [of actors and theatre-makers].”

Born in India and raised in Southall, west London, Sharma fell in love with theatre at school and worked as an actor for 10 years before the strain of touring – he has a physical impairment – prompted him to switch to directing. He worked at Graeae, Manchester Royal Exchange and Birmingham Rep before joining the Kiln.

Getting the top job left him “speechless”, Sharma says, and he feels the pressure to match up. “On a personal level, because so few disabled people have been in these positions, I feel it’s really important to go ‘Disabled people can do this job equally if not better than their non-disabled counterparts.’ I’ve got a point to prove – not just for myself but for the next generation.”

What’s the hardest part of your job?

[Finding] family time.

What can’t you live without at work?

Sense of humour. If you ask people, sometimes they’ll say the sense of humour wasn’t needed, but I just put it in, because we’re not doctors or whatever, we’re making theatre. We should really just chill out a bit.

Sell theatre to someone who says they’re not the theatregoing type.

Do you like stories? Do you like stories being told to you live? Then theatre is for you, because that’s essentially what it’s about.

Are ticket prices too high?

It’s so hard, because making theatre is expensive, right? So some of [the high pricing] is for good reasons. But it has to be accessible. I grew up on a council estate, and if I didn’t have the under-26 offers or whatever, I wouldn’t have been able to engage. And then it does become elitist. So it’s for us to strive to make theatre prices accessible by working harder to get people who might have a bit more money to support those that can’t access theatre like they can.

Kate Wasserberg: ‘It’s been like coming home’

Theatr Clwyd, Mold, Flintshire; in post since September 2024

If having faith in Wales and its creative talent was a key requirement for Theatr Clwyd’s board when appointing their new artistic director, they found the ideal candidate in Kate Wasserberg. The 44-year-old from Stafford “fell hook, line and sinker for Wales” when she first worked at the Flintshire theatre in 2007, rising to associate director under Terry Hands. She went on to set up the Other Room theatre in Cardiff, run new writing company Stockroom and direct James Graham’s Boys from the Blackstuff, but returning to Mold for her “dream job” has felt “in every way like coming home”.

Beyond its theatrical offerings, one of the things Wasserberg loves about Theatr Clwyd is its work with communities. She aims to create a world-class workplace for her staff, with on-site counselling services, and has conducted a review of freelancer pay, adding up all the time and effort it takes to make a show. “As a result, freelancer fees have gone right up.”

Covering these costs “will means that we make slightly fewer shows,” she says. The theatre is also diversifying. When Clwyd’s brand-new premises open this summer, at the cost of £50m, there will be event spaces and a restaurant in partnership with chef Bryn Williams. “So they all help [financially]. They are all part of the picture.”

Wasserberg sees UK theatre as “an incredible community that is hanging on by its fingernails… People often say ‘Theatre or the NHS?’ But if you’re running a programme for at-risk children where you’re engaging with them using the arts, you might be part of the picture that reduces the burden on the NHS. So I think theatre is doing its bit.”

What are the top three skills you need as an artistic director?

Candour, empathy and curiosity.

Dream person to work with – dead or alive?

I would make a musical with Joni Mitchell. I love her. She’s a storyteller. Every single one of her songs is like a play.

What’s the hardest part of your job?

Saying no. Sometimes, you love the work but it’s just not right for your building.

Sell theatre to someone who says they’re not the theatregoing type.

Have a night out and let us tell you a brilliant story. You’ll feel better. I really do think that. In an increasingly atomised society, people are genuinely craving those moments of togetherness and community.

Nadia Fall: ‘Theatre is the greatest deep therapy you’ll get’

Young Vic, London SE1; in post since January

“It is a bloody privilege to do it,” says Nadia Fall, who takes over from Kwame Kwei-Armah as artistic director at the Young Vic this month, “but it is your life, seven days a week, and it does become who you are. The theatre becomes as much your family as your real family.” That, she thinks, is why there’s been an exodus of artistic directors from British theatres lately. “It takes some stamina, and lots of people, once they’ve done one stint, they don’t want to do another. Also, post-Brexit and Covid, it’s more full-on than it ever was.”

Fall, who grew up in south London not far from the Young Vic, as well as in the Middle East, took up her first artistic director position at Theatre Royal Stratford East in 2017 and had a terrific run, putting on varied productions such as August Wilson’s King Hedley II, which she directed, and an Olivier-winning version of Britten’s Noye’s Fludde with the ENO featuring local schoolchildren. “I absolutely loved it,” she says of her seven-and-a-half-year tenure, but Covid struck midway through “and I don’t think things have been the same since. It’s costing more and more to make a show, and we’re getting less and less [money]. And loads of talented people have left the industry because it wasn’t viable.”

Nonetheless, she’s thrilled to be starting at the Young Vic. “It’s got a similar spirit to Stratford East: it’s still a bit of a mischievous child. It likes stories that provoke and ask questions. What’s exciting to me artistically is that the audiences really want to be challenged there.”

What three words sum up your theatre?

Rebellious, global, event.

What one show should we come and see there?

James Graham’s Punch. He’s got the Midas touch and I’m really interested in a play around restorative justice. I’m so glad it’s coming to London.

Dream person to work with, dead or alive?

My friend Lesley Manville. There isn’t a word that actor utters that you don’t believe, she is so authentic and nuanced, yet at the same time like a little titan. I thought she was extraordinarily in Oedipus. There’s nothing she can’t do, and I can’t believe we haven’t worked together. We must correct that. If you put it in the paper she’ll feel guilty and she’ll have to do it.

What’s your favourite theatre in the world (not your own)?

Epidaurus outside Athens. It’s thousands of years old, and you can imagine people thousands of years ago sitting there watching the ancient plays. We took Phèdre with Helen Mirren there when I was an associate at the National and there were howling wolves and bats flying across the set. It was a proper spiritual experience. It’s electric.

What’s the hardest part of your job?

I always wish I could give birth to time.

Sell theatre to someone who says they’re not the theatregoing type.

It’s like saying you don’t like music. You just need the right song for the right mood that fits you. People who say that just haven’t found their jam yet, just need to be matchmade with the right show. And do you know what? It’s the cheapest form of group therapy that you’ll ever get. It sounds a bit frivolous to say that, but it’s actually proven.

Life is hard: the climate catastrophe is unfolding, there’s war blazing around the globe, and it’s really tough for people – and where do we congregate? We congregate in a theatre and we practise the act of empathy by watching plays. And that is group therapy. That’s what the Greeks got their citizens to do, to practise the act of empathy. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Physiologically, our bodies change when we’re watching a play. Our heartbeats sync with the actors on stage, with each other. That stuff is real. So I think it’s good for your health.

Nathan Powell: ‘The rehearsal room is my happy place’

Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse; in post full-time since December 2024

It takes several tries to pin Nathan Powell down for an interview. That’s because, although he started part-time as creative director at Liverpool’s Everyman and Playhouse theatres in August, he’s been dashing around fulfilling prior commitments, directing The Mountaintop at Curve in Leicester and then Alice in Wonderland at Shakespeare North.

When we finally speak, the London-born writer-director tells me that for many years, his “bread and butter has been in community arts or working with young people”. He moved to Liverpool seven years ago to work with youth theatre company 20 Stories High and stayed to start a family, though freelance gigs have taken him all over the country. One of his concerns at Everyman and Playhouse is making the spaces accessible to all. “I haven’t always felt comfortable in theatres,” says Powell, “and I think that’s cultural.” But he believes attitudes are shifting. “It feels like theatres want to be more open spaces that when I was younger.”

Unlike others here, Powell’s title is creative director rather than artistic director. The differences, he says, are fairly minimal. “It’s partly about broadening the scope of who could apply. They were very specific that you didn’t need that sort of artistic background [as a writer or director] to be in the role.” There’s less of an emphasis on staging work himself and more on facilitating others. To this end, Powell is keen to programme shows that are about or by local people while making room for risk-taking. His first season opens in April with his own play Takeaway, about a family-run Caribbean shop during riots in Liverpool, and also includes an experimental piece by Wirral-born playwright Billie Collins entitled The Walrus Has a Right to Adventure.

What are the top three skills you need as an artistic director?

Kindness, patience and a thick skin.

Who or what first got you into theatre?

I remember my auntie took me, my sister and our cousins to see The Lion King in the West End when we were really little. I don’t actually remember the show very much, I just remember being wowed and like, “Oh my gosh, this is insane.” I didn’t expect to walk into such an inconspicuous building and see all of this on stage.

Best production you’ve seen recently?

I Am Steven Gerrard at the Liverpool Royal Court. I remember being in the audience with lots of people that thought they were coming to see a show about Steven Gerrard, who were all very excited, and then one of the first lines of the play is something like, “I fucking hate Jürgen Klopp,” and the whole audience gasped. [It was a] story in beautiful verse about this young man trying to find his identity because he couldn’t care less about football, and the audience were with him the whole way through. It was a beautiful piece of theatre.

What can’t you live without at work?

Laughter and silliness. The rehearsal room is my happy place. I’m not much of an “organised fun” person, but that’s the only place where I like organised fun, which is really just having a place where we can just laugh and enjoy what we’re doing.

Are ticket prices too high?

What surveys of ticket prices often leave off are regional theatres – the focus is on the West End. We work pretty hard to make sure that our ticket prices stay accessible. If you’re under 26 you can sign up to YEP [the theatres’ free youth membership programme] to get £5 tickets. But of course, it’s still a barrier to lots of people, isn’t it? All of your tickets could be £5, and still some people might decide they don’t want to spend that £5 – they’ve got lots of other things to pay for and everything is very expensive. Interviews by Killian Fox

.png) 2 months ago

24

2 months ago

24