When Elon Musk endorsed the far-right Alternative für Deutschland on X as the only party that could “save Germany”, followed by an opinion article in Die Welt promoting the AfD in the forthcoming federal elections the backlash was swift. “Germany must not tolerate Musk’s transgressions,” declared the publisher of the liberal newspaper Tagesspiegel. “How did Elon Musk’s election propaganda for the AfD make it into Welt?” asked another commentator, accusing Welt’s publisher, Axel Springer, of betraying its own principles. The Spiegel columnist Marina Kormbaki labelled Musk’s intervention the “breaking of a taboo”.

The outrage was justified. Musk’s apocalyptic rhetoric and alignment with forces often labelled extremist are deeply unsettling in a country still grappling with the weight of its 20th-century atrocities. His political meddling – from the US to the UK and now Germany – follows a disturbing pattern of self-aggrandisement cloaked in dangerous ideology.

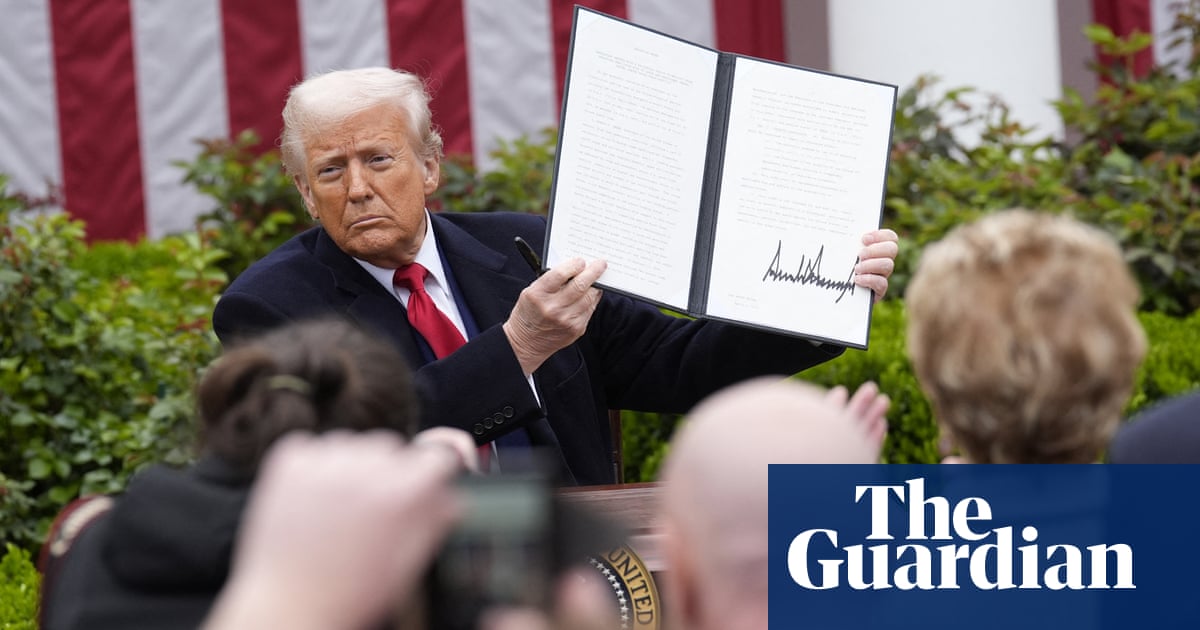

His immense wealth and global influence, magnified by his acquisition of the social media platform X, as well as his strong ties to authoritarian figures including Donald Trump, make this interference a brazen intrusion that strikes at the heart of democratic integrity. In Germany, where foreign meddling in domestic politics is anathema, this audacity rightly struck a nerve. As the vice-chancellor, Robert Habeck, put it: “Hands off our democracy, Mr. Musk!”

At the same time, Musk’s views are hardly a surprise. His rightward drift has been years in the making, culminating – some might say, logically – in his support for a party that mirrors some of his core obsessions: nationalist salvation fantasies, natalism, austerity dogmatism. His endorsement aligns with a broader shift in Germany’s public discourse, where far-right narratives have been steadily normalised in both conservative and liberal circles.

Musk’s argument in the article itself was so simplistic it sparked speculation about whether it might have been AI-generated. His reasoning hinged on praising the AfD’s “political realism” and deregulatory agenda, coupled with the claim that the party couldn’t really be “far right” because its co-leader, Alice Weidel, has a same-sex partner from Sri Lanka. A superficial logic that chips away at the carefully cultivated aura of Musk as a brilliant, if eccentric, entrepreneur.

What’s even less surprising than Musk’s positions is Die Welt handing him the microphone. Axel Springer, Europe’s largest publishing house, has long played a role in normalising far-right ideas in Germany. Springer, which publishes the Bild tabloid and the Welt daily, reaches millions and actively shapes German public opinion. Over the years, Springer’s German outlets have steadily amplified anti-immigrant narratives which in turn has arguably helped legitimise the far right.

Take Bild, Springer’s infamous tabloid powerhouse and Germany’s most widely distributed newspaper. In 2023, it published a 50-point manifesto demanding that immigrants respect “German values”, claiming: “We are experiencing a new dimension of hatred in our country – against our values, democracy and Germany.” The text leaned heavily on anti-Muslim tropes, painting immigrants as knife-wielding savages who scorn women, education, nudity and law enforcement.

These narratives have seeped into mainstream discourse. The chancellor, Olaf Scholz, famously promised mass deportations. After a suspected Islamist knife attack in Solingen, leading political figures from the Greens to the Social Democratic party suggested that deportations were necessary for domestic safety, an argument alarmingly similar to the AfD’s ethnonationalist agenda. Liberal outlets such as Zeit published essays questioning whether immigrants could “civilise”. Today, the AfD’s cultural essentialism resonates far beyond its voter base.

Musk’s influence obviously surpasses that of any ordinary commentator in Germany. Yet, within the Axel Springer ecosystem, his intervention felt less like an outlier, more like a blunt articulation of what many have gestured to for years. Just days before Musk’s opinion piece, Welt’s publisher, Ulf Poschardt, penned a perplexing column praising Musk’s admiration for Richard Wagner, Ernst Jünger and German techno culture. Poschardt argued that Germany needs a figure like Musk to combat its economic stagnation, while carefully distancing himself from the tech magnate’s boosting of the AfD on X. This calculated tightrope act – appearing to flirt with far-right ideas without explicitly endorsing the parties that most openly embody them – has become emblematic of Axel Springer’s approach.

Musk’s personal relationship with Axel Springer’s CEO, Mathias Döpfner, adds another dimension to the story. Döpfner has long admired Musk, calling him “the greatest visionary on the planet” in a 2020 interview. According to Spiegel, Döpfner also encouraged Musk to buy Twitter, offering to help transform it into a “true platform for free expression”. In 2023, Musk was among high-profile guests at Döpfner’s 60th birthday party, joined by Eva Vlaardingerbroek, a Dutch far-right influencer known for promoting conspiracies such as the “great replacement” theory. Such alleged entanglements between tech oligarchs, media powerbrokers and politicians underscore the growing international networks fuelling today’s global far-right resurgence.

Musk’s opinion article also triggered dissent at Welt. Several journalists publicly criticised the decision to publish it and Welt’s opinion editor Eva Marie Kogel resigned in protest. This is commendable, but it also raises questions: where was this kind of resistance when Welt platformed columnists who derided welfare recipients as lazy or questioned Germany’s firewall around the AfD? Why did it take Musk’s name to sound the alarm?

The affair highlights the extent to which right-leaning media and politics operate in tandem in Germany. In May 2024, after riot police violently dismantled a pro-Palestinian student camp in Berlin, Bild vilified more than 100 academics who signed a letter advocating nonviolence, branding them “Universitäter” (a slur combining “university” and “perpetrators”). The then education minister, Bettina Stark-Watzinger, wasted no time echoing the tabloid’s condemnation.

This pattern – stoking outrage with rightwing agendas – reflects how Germany’s establishment increasingly co-opts far-right rhetoric to undercut its appeal. But instead of containing the AfD, this strategy has further legitimised its ideas, fuelling its historic successes in states such as Saxony and Thuringia.

Musk and Weidel are now poised for a live discussion on X billed as a conversation on “freedom of expression and the AfD’s ideas for a sustainable Germany”. With the AfD polling second nationally and eyeing up to 20% of the vote, its influence on public discourse continues to grow. While Germany’s established parties still formally reject coalition-building with the AfD, their increasing adoption of AfD-style rhetoric tells a different story.

Against this backdrop, fixating solely on Musk’s endorsement feels like a distraction. Yes, his alignment with the AfD is alarming. As is his promotion of figures such as the German rightwing influencer Naomi Seibt, whose positions Musk has repeatedly endorsed. But the deeper issue is that many of the AfD’s core ideas – anti-migrant culture wars and ethnonationalist alliances – are already entrenched within Germany’s political mainstream.

Allowing Musk to use his outsized influence and resources to meddle in German or European elections would be a grave mistake. Yet focusing on Musk as an anomaly is hypocritical. It allows Germany’s liberal establishment to avoid reckoning with its own complicity in normalising reactionary ideas. With the election just weeks away, Germany must face this challenge head-on. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

-

Hanno Hauenstein is a Berlin-based journalist and author

.png) 2 months ago

34

2 months ago

34