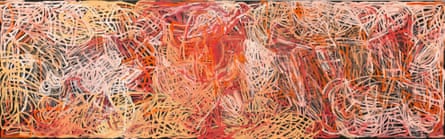

Painting quickly and directly, with few revisions and no changes of heart, Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art is filled with exhilarations and with difficulties. Part of the pleasure of her art is that it is so immediate, so visually accessible, with its teeming fields and clusters of finger-painted dots, its sinuous and looping paths, its intersections and branchings, its staves and repetitive rhythms. You can get lost in there, and sometimes overwhelmed. You can feel the connection between her hand and eye, and the bodily gestures she makes as she paints.

Kngwarray’s paintings might well remind you of a kind of gestural abstraction they have nothing to do with, and which the artist would never in any case have seen. The things we look at in Kngwarray’s art are about an entirely different order of experience to the similar kinds of brushstrokes driven this way and that around other, more familiar canvases we might also find in Tate Modern, where her retrospective has arrived from the National Gallery of Australia. But this similarity is also one of the reasons Kngwarray became famous in the first place.

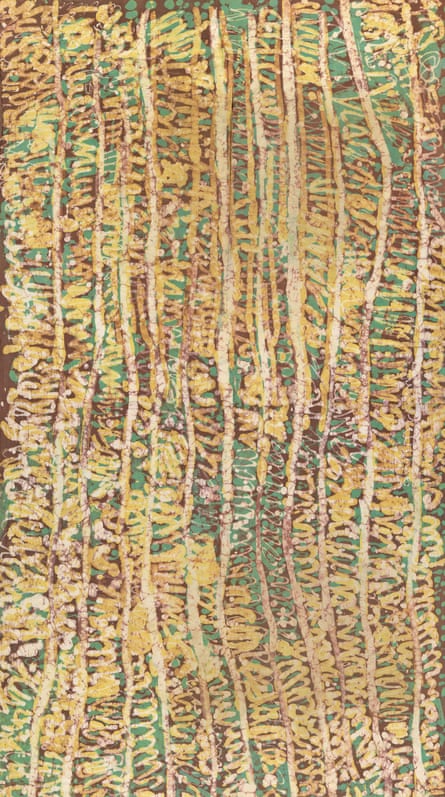

Kngwarray only painted for the last six or seven years of her life, leading up to her death in 1996. She made upwards of 3,000 paintings. Before that she spent a little over a decade making batik prints, which were no less inventive than her paintings; foliage and flowers cover the cotton and later silk, lizards and emus erupt from the fabrics which swarm with life and her own lively and confident graphic touch. Her art always had a spirit of improvisation and immersion in the process, first in the complexities of printmaking and then in painting with thin, quick-drying acrylics.

Born around 1914 in Australia’s Northern Territory, Kngwarray spent her entire life around her ancestral Alhalker Country homeland. Colonisers had first appeared there in the 1870s, and confrontations had led to many Aboriginal deaths. As a child, Kngwarray learned to run away from the whitefellers. First came the surveyors, then the telegraph, and then police, trackers and settlers, digging boreholes for water for their sheep, goats, horses and cattle, and appropriating sacred ancestral lands. Missionaries came with camels, magic lantern shows and a gramophone. In the early 1930s, 100 or more Aboriginal people in the area were shot or poisoned by police and a colonist leaseholder (who had been involved in previous atrocities), in retribution for spearing cattle.

Kngwarray spent much of her adult life on stations, watching cattle and sheep, working in kitchens and minding children. She spoke little English, and like other Aboriginal people, generally worked for rations rather than payment. The sheep and cattle stations couldn’t function without their labour. She was an accomplished hunter-gatherer. Photographs in the fascinating catalogue show Kngwarray skinning echidnas and bearing a lizard by the tail.

By the 1970s, land began to be returned to its traditional owners, and adult literacy and numeracy courses were set up, leading, circuitously, to a batik printing course at the former Utopia station homestead, as a possible avenue to self-employment for women in the area. Then in her mid-60s, Kngwarray became, as she said later, “the boss of batik”. By the early 1980s, batiks by the Utopia artists began to be recognised and exhibited, firstly in Australia then further afield. By the end of the 1980s, an Aboriginal controlled organisation took over the Women’s Batik Group, and began distributing paints and canvas as an alternative to the highly labour-intensive batik.

The imagery, motifs, iconography, and even spatial sense of Kngwarray’s work comes directly from her Indigenous Anmatyerr culture; women’s songs and ceremonies involving communal body painting – using natural pigments mixed with fat to stripe breasts, torsos and arms, ceremonies involving scarification, and telling stories with the sand at one’s feet, using leaves and twigs and other ephemera to represent characters, situations, weather. All this storytelling and bodypainting takes place while sitting on the ground, which is also where Kngwarray put herself to paint. For larger works she would sit on the unstretched canvas and work from within it.

Painting for her was a continuation of her cultural practice – although it appears she was hesitant about revealing the stories her paintings told. This isn’t unusual for any artist. Its good to have secrets and mysteries and things unexplained. Where her paintings are titled, they might be called ‘Everything, or My Country, or be named after a specific place or a type of yam, an old man emu with babies, or appear to describe a journey through the bush.

Arrow shapes turn out to be the footprints of emus in the sand as they make their way from here to there, pausing to eat fruits or grain or insects in their path. Tangles of line depict the vine of the pencil yam, whose presence betrays the tubers underground and the seed-pods from which the artist got her name Kam. “I am Kam! I paint my plant, the one I am named after,” she once explained. “They are found growing up along the creek banks. That’s what I painted. I keep on painting the place that belongs to me – I never change from painting that place.”

Sometimes the paintings are meticulous in their ordering, and at other times a line will scrabble all over the place, rolling and slewing around the large canvas. There are blizzards of dots, translucent white lines crossing and recrossing the territory of the canvas, and emphatic black lines crazing a white surface with marks that nearly cohere – but into what? Often, I’m left teetering. One long suite of 22 identically sized canvases, all dotted and clotted and clogged with colour, seems to evoke a consistent though shifting optical terrain, while banks of horizontal and vertical lines evoke the body markings of a traditional ceremony, and the sense of bodies in motion. The closer I get to Kngwarray’s art, the more it recedes. On a physical and optical level, it feels accessible, in ways that are a bit overfamiliar. But that wasn’t what the artist was doing. Her art was about life and connectedness to something more than just the art world and its manners.

.png) 2 months ago

18

2 months ago

18