A Robin Smith square cut was more than a whip‑crack snap of the bat. For English cricket fans of the late 80s and early 90s, it was a nudge in the ribs that, underneath the pastings, the dismal collapses and Rentaghost selections, the national team would fight another day.

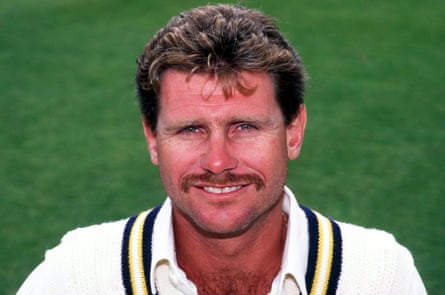

Smith’s cut, alongside a David Gower cover drive, gave hope where there was little left in the bucket. Those famous forearms – half oak, half baobab – the white shirt unbuttoned past the clavicle, the chain glinting through his chest hair, smelt enticingly like bravery, and old spice and one last throw of the dice.

The sight of Smith marching out to bat – as an opener (in four Tests), No 3 (six), No 4 (30), No 5 (19), No 6 (14) or No 7 (twice) – those charmingly indecisive selectors never could quite place him – was a high point in a largely post-Botham era, a clear-the-bars alarm for those in the ground and a stay‑your‑ground sign to those on the sofa.

Like fellow South Africans Tony Greig and Allan Lamb before him and Kevin Pietersen after him, Smith was bigger and better and more sexy than his Test average – which, incidentally, was a healthy 43.67 – second only to Graham Gooch among English batters during the period of his Test career. He was utterly fearless in the face of extreme pace, beyond any expectation, as fast bowlers reared up at meeting their match and came harder.

Watch the highlights of him batting against Ian Bishop at Edgbaston in 1995, just six months before he played his final Test. Bishop is relentless, skilful, brutal – and Smith, with barely a flinch, takes blows on the elbow, the shoulder, the rump, but he evades even more. Dainty back bends, swaying leather-sniffing, dinky knee drops, all were part of his back catalogue long before yoga and pilates were the staple of a sportsman’s daily routine. Smith hit 41 in England’s second innings of 89 all out in that match – opening because Alec Stewart couldn’t bat after injuring a finger behind the stumps on a pitch that the captain Mike Atherton said later was the worst he had encountered in any Test. Atherton also told everyone that Smith’s 41 would have been worth a hundred had it been made anywhere else.

Smith made his England debut in 1988, dropped into an England team in disarray during the famous summer of the four captains. Chris Cowdrey was his captain for that match – and would never play for England again. But Smith took it all in his stride and the next year scorched two hundreds and a 96 during the 4-0 thrashing by Australia in England.

Of all his nine Test centuries, two stick most memorably in the mind. His 101 in the fifth Ashes Test at Trent Bridge that dismal 1989 summer, after Australia had racked up 602 for six declared, and Smith had stormed in with the score one for two – Martyn Moxon and Atherton back in the pavilion for ducks. He ravaged the Australians, those square cuts screaming across the Nottingham grass and you can sense the joy in the crowd that someone, at last, is giving them something to cheer at, a stick of some sort to wave at the gimlet-eyed baggy greens. I don’t think that, even in this Indian Premier League era, anyone has cut the ball harder.

And his 175 against the West Indies at St Johns in April 1994 – an almost forgotten innings as it came in the same match as Brian Lara grabbed the headlines with 375. But against Curtly Ambrose, and Courtney Walsh, it was an innings of pure-gold defiance.

after newsletter promotion

Maybe England players seemed more human to us then because we could see their faces when they undertook the cruel business of batting. We could smell their fear and see the frustration in their eyes. Smith would wear a cap when he could, otherwise his helmet was without bars or visor, balanced on that famous hair, which panned behind him in a series of shampoo‑and-set waves.

In the end, it turned out that the larger-than-life cricketer and the cavalier cape didn’t match the vulnerable human underneath. His autobiography The Judge, written with Rob Smyth, revealed the loneliness and sadness behind those big-man strokes, and the bereft figure left once cricket had decided he was no longer needed. “The Judge was a fearless warrior,” he wrote. “Robin Arnold Smith was a frantic worrier.” I hope he knew how much we all loved him.

.png) 2 months ago

62

2 months ago

62