The poolside bar at the Nana backpackers hostel in central Laos should have been an idyllic spot for a free happy hour on a mid-November evening.

Among those staying at Nana were two pairs of best friends – 19-year-old Australians Bianca Jones and Holly Bowles, and Freja Vennervald Sorensen, 21, and Anne-Sofie Orkild Coyman, 20, from Denmark. All four were drawn to south-east Asia’s famed backpacking route that has for decades enticed young travellers seeking carefree, sun-drenched moments.

They would never have imagined that the adventure of a lifetime would turn to tragedy.

While the childhood friends from Melbourne didn’t know their Danish counterparts, the young women’s parents are now bound together in a fight for answers and justice. Their daughters are among six tourists – including British lawyer, Simone White, 28, and a US man – who became ill and later died in a suspected mass methanol poisoning on 12 November in Vang Vieng, where they drank what is believed to have been methanol-laced alcohol.

Four months on from that night at the hostel, the grieving parents are speaking out amid fears that they will never see Lao authorities hold anyone to account for their children’s deaths.

The Guardian can reveal there has been a joint diplomatic push by Australia, the United Kingdom and Denmark, which Karsten Sorensen, father of Freja, says is “brilliant”. But he, Freja’s mother, and Anne-Sofie’s parents remain in the dark as to whether their daughters’ deaths will be included in a criminal investigation into the suspected mass methanol poisoning, as the death certificates provided in Laos make no mention of the lethal chemical.

Since their daughters’ deaths, the parents of Simone, Holly, Bianca, Freja and Anne-Sofie have stayed connected in a WhatsApp group, where they exchange photos and updates received from their respective national governments. “They’re really the only people that can understand what we’re going through,” says Shaun Bowles, Holly’s father.

The families, who say the Lao government has made no direct contact with them since the deaths, have publicly criticised the lack of transparency and communication from the country’s authorities, who rejected foreign assistance with the investigation. The British ambassador to Laos raised the case, alongside the Denmark and Australian embassies, with Laos’ ministry of foreign affairs on 26 February, sources tell the Guardian.

Death certificates raise questions

In a small temple on the outskirts of Vientiane, later in November, Freja and Anne-Sofie’s fathers identified their daughters’ bodies.

Didier Coyman, the father of Anne-Sofie, says he was told no autopsy could be conducted in Laos due to a lack of capabilities in the developing country. Due to the bodies being embalmed before repatriation via Bangkok, autopsies could not be undertaken in Denmark, Sorensen says.

Sorensen and his partner, Rikke, now fear their daughter’s death may not be treated as part of the cluster of suspected methanol poisoning deaths due to the absence of postmortem toxicology testing.

“That is one of the horror scenarios that I have … that would not be acceptable,” he says. The death certificate for Freja, viewed by Guardian Australia, states the 21-year-old died from “acute heart failure”. Lao authorities also concluded that Anne-Sofie died from heart failure.

“How can you explain two young women at the ages of 20 and 21, with no kind of health issues before, suddenly on the same day, having a heart attack in the same setting, the same hostel, where a number of others have been linked to methanol poisoning?” Sorensen says.

“There’s no official documentation of facts underpinning that our girls passed away due to methanol poisoning.”

The Danish ministry of foreign affairs says that Lao authorities have confirmed they are “currently investigating the case”. Sorensen says the Danish ambassador in Vietnam, who is communicating with the authorities, asked the families if they knew whether any toxicology tests or autopsies had been done.

“That was then mentioned by the ambassador as being one of the risks in the investigation here, that they did not have the facts around our girls,” he says.

“You could, at any point, come up with a situation saying that, well, we have no recognition of this being methanol poisoning because there are no facts behind it. You have no claim to any kind of recognition to some kind of wrongdoing.”

‘Zero confidence’ in investigation

All six foreign tourists who died had stayed at Nana backpackers hotel but police have not confirmed if the suspected methanol poisoning occurred there or at one of the many bars in Vang Vieng.

Hostel staff detained by Lao police in November were recently released, prompting calls from the Australian and Danish parents for travellers to boycott the country until its authorities properly investigate the deaths.

Bianca’s father, Mark Jones, believes the detainees’ release suggests the investigation has come to a “thumping halt”. Bowles says he has “zero confidence that anything is actually being done”.

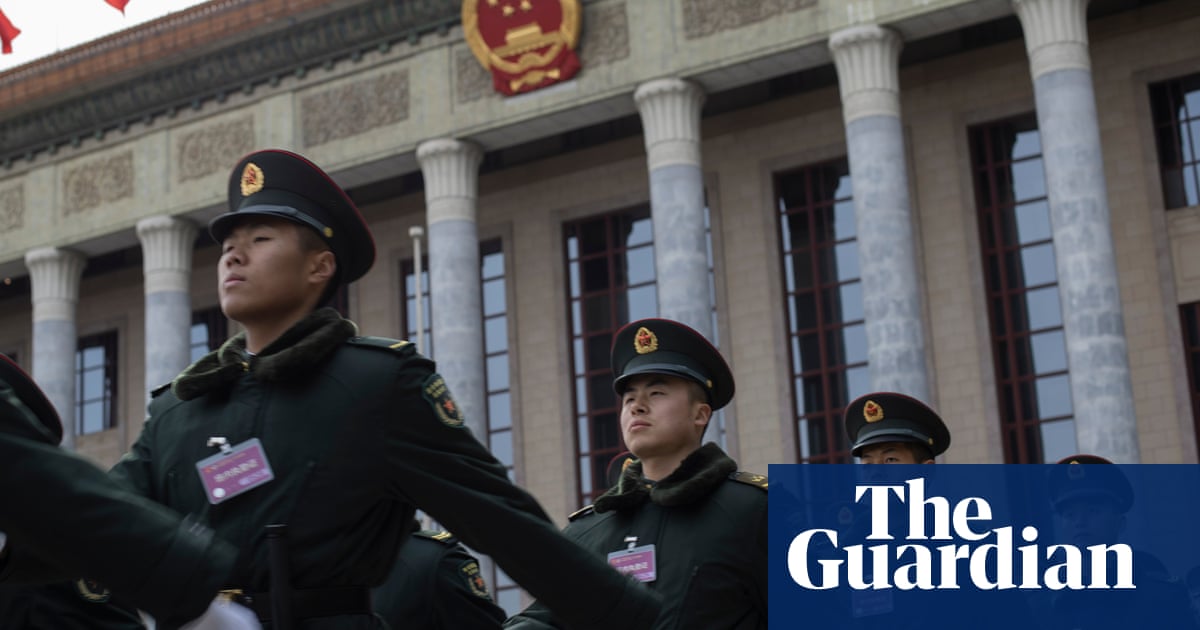

Public information about the police investigation in Laos – a one-party communist state where the media are tightly controlled – has been sparse. The Lao government’s only public statement since the mass poisoning vows to bring the perpetrators to justice under the law.

after newsletter promotion

In the UK last month, Simone’s mother, Sue, tells ITV she believes it is “unlikely” any individual will be convicted over her daughter’s death.

The families of the two Melbourne victims have sought to meet with Laos’ ambassador to Australia to discuss the case, but say they have received no response to an invitation extended by the federal government on their behalf. The Lao embassy in Australia has been contacted for comment.

The fight for justice

The Australian families, who rushed to Thailand to be with their daughters while they were on life support, have now made it their mission to raise awareness about the risks of methanol poisoning as they pursue accountability.

In south-east Asia, brewing bootleg liquor from ingredients such as rice and sugarcane is a cultural norm. These are sometimes mixed with methanol – as a cheaper alternative to ethanol – the key component in alcoholic drinks. Unlike ethanol, which can be consumed in small amounts, methanol is toxic to humans. Just 30ml – a single mouthful – is the lethal dose.

Médecins Sans Frontières has tracked more than 14,000 suspected methanol poisoning deaths since 1998 based on information in news reports and publications. A brief by the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade reports that illicit alcohol in Laos accounts for up to a third of alcohol consumed in the country.

A Laos-based lawyer, who requested anonymity due to fears over speaking publicly, says two articles in the country’s penal code can be used to prosecute someone found to be responsible for manufacturing methanol that leads to mass poisoning. It carries a maximum penalty of up to 10 years in prison. It is unclear if prosecutions have ever been brought under these sections of the penal code.

For Bowles, 10 years in prison “seems very soft for knowingly producing something that can take people’s lives”.

Jones hopes someone will be punished for the deaths and that it will act as a deterrent to those making and selling bootleg liquor. “Every single morning, every single day, every minute of every day, we have big holes in our hearts, and we don’t want that to happen to other people.”

He says the families “have got the sentence for the rest of our lives”.

“Our children have got this sentence for the rest of their lives. Our parents have had their granddaughter ripped away from them. No penalty is going to ever fix that.”

Sorensen is also determined for Lao authorities to recognise the “wrongdoing” that led to his daughter’s sudden death. “There needs to be some kind of accountability around what’s going on,” he says.

The group of grieving parents is committed to pursuing answers and justice for their daughters.

“I think this is what they’d want us to be doing,” Bowles says.

“If it was one of us, or if it was one of their friends or another family member, they would be on the frontline, making sure that someone was held accountable.”

.png) 3 months ago

46

3 months ago

46