Charles Aznavour – For Me … Formidable

This year I completed Duolingo in French, but found myself no closer to being able to carry out what I would call a conversation. (Exchanging likes and dislikes doesn’t count.) I decided to go Paris to practise on some unsuspecting locals, procured via Hinge. One man proved surprisingly game: he not only spoke excellent English but was a self-described anglophile, more up to date than I am on UK politics and truly passionate about Marks & Spencer.

Our few days together were a productive cultural exchange: I introduced him to Fawlty Towers and The Great British Bake Off, he introduced me to île flottante and Charles Aznavour. I’d never heard of Aznavour before (I’ve since learned that he’s been called the French Morrissey), but when my self-appointed tour guide played For Me … Formidable, I was charmed by the jaunty show tune with comic wordplay.

Aznavour switches somewhat haphazardly between English and French, trying to find the words that most effectively convey the depth of his emotion. With its bombastic brass and heart-on-sleeve sentiment, For Me … Formidable is from another time, one where romance was not brokered with swipes and likes, but it captured the playful goodwill generated between my date and me in our effort to communicate.

By the song’s end Aznavour’s narrator has begun to second-guess his feelings, wondering whether words might be failing him because his love is superficial, not language itself. Turns out, my date and I also reached a limit on mutual understanding – but when I returned home to England, with new French vocabulary and more confidence in expressing myself, I took For Me … with me as a reminder of the life-affirming value of the search for the right words. Elle Hunt

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan live in Birmingham, 1983

I was spurred into listening to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan by the release this year of his “lost” 1990 album Chain of Light, then spurred by my love of it into looking for live videos of the late qawwali singer online. Most of the footage out there is what you might expect: filmed after his mid-80s international breakthrough, in concert halls filled with a reverential, predominantly white audience, there to hear the master of this mystical, devotional music. And then I chanced on an 18-minute camcorder recording of Khan performing the qawwal Shahbaz Qalandar in the Royal Oak, Birmingham, in 1983.

Here, the crowd are exclusively Asian and they aren’t rapt or reverent: they’re going absolutely nuts. There are people dancing – one with such abandon that he’s eventually led away by a friend in time-honoured “you’re just embarrassing yourself now” style – and people literally throwing money at the Pakistani singer and his fellow musicians as they perform. One guy at the front looks as if he’s head-banging. Another is so overwhelmed, he suddenly stands up, takes off his shoes, chucks them across the room and sits down again.

It’s not just that the vocals are incredible and the music is fantastic, although they are and it is – cyclical, hypnotic, with a gorgeous, descending refrain at its centre. It’s the giddy excitement that surrounds the performance, a transcendent joy that still feels infectious transmitted via a YouTube link 30 years later. Watching it buoys me, makes me feel better: while it’s playing, everything is momentarily all right with the world. Alexis Petridis

Teresa Tang – The Moon Represents My Heart

When I was growing up in an immigrant family in New Zealand, 20th-century Chinese pop songs were common backdrops to family life. There were ballads my mother would play on the radio; tunes on the television shows we would watch together; songs that blared overhead in the Chinatown shops.

I grew familiar with some of them, but only ever in terms of how they sounded: a catchy hook, or lyrics that struck the ear. But I could not name any songs, let alone artists. That changed this year when I searched for songs to play at a wedding. Deep in the reserves of my memory, I thought of it: 月亮代表我的心 (The Moon Represents My Heart), a melancholic yet wistful love song from the 70s by Taiwanese composer Weng Ching-Hsi and songwriter Sun Yi that was not only a staple in my household, but in homes across China and beyond.

Hailed as one of the most beloved Chinese song of all time (Kenny G and Jon Bon Jovi have covered it), the song has several versions, but the most famous is by the 20th-century Taiwanese pop star Teresa Teng, who sings it with her trademark mellifluous voice, as sweet and clear as honey. Teng herself was a megastar across the continent – in China, it is said that her popularity rivalled that of Deng Xiaoping.

A deeper dive into her catalogue unveiled more gems; another famous song of hers is called Tian Mi Mi (How Sweet.) At first I recognised them as the ambient backdrops to my childhood, but now they were also announcing themselves to be rich, deeply alive songs in their own right. It feels very special, how music can carry us between our past and our present, its meaning changing and growing as we do. Rebecca Liu

Bobbi Humphrey – Blacks and Blues

“Where’s she coming from? Where’s she going to?” ask the sleeve notes to Bobbi Humphrey’s breakthrough album, 1974’s Blacks and Blues. A flute prodigy from Texas, discovered by Dizzy Gillespie at a talent contest, she relocated to New York and was signed by Blue Note after slaying amateur night at Harlem’s Apollo theatre. But where was she going? Two albums of pleasant-enough soul-jazz covers suggested “nowhere special”. But a conversation with trumpeter Donald Byrd after a gig together sent Humphrey in search of the Mizell brothers, Larry and Fonce, the production duo who had overseen Byrd’s lucrative transition from hard bop to fusion.

For Blacks and Blues, the Mizells cooked up a slate of tracks that grazed fusion but pulled back from the muso intensity in favour of adept, perfectly judged grooves – light enough to let the sunshine in, but funky enough to ground Humphrey’s lyrical, questing flute. She and the Mizells cut three hit albums together that captured a crossover moment for jazz – the sound of mid-70s bougie Blackness at its most glorious. But on Blacks and Blues, her gauzy visions retained an edge audible in vignettes such as Chicago, Damn (“rapping in the park after dark”) or the moody title track.

Humphrey parted from the Mizells after moving to Epic in 1977, and some fine soul-funk records followed. But it’s the trilogy at Blue Note that seduced me to her dreamy, aspirational escapism this year: 1975’s Fancy Dancer is my favourite of the bunch, with the zesty Latin bump of opener Uno Esta absolutely irresistible. Stevie Chick

Paramore – The Only Exception

At the start of 2024, teetering on the brink of full social media immolation, I made the bold decision not to join TikTok. Fast-forward 11 months and I now spend countless hours on Instagram transfixed by all the TikTok content that makes its way on to my “for you” feed. A few months ago, nestled in among compilations of people falling over, straight couples pranking each other and vintage 80s Kylie clips, I found a video of Paramore’s Hayley Williams performing an impassioned, vocally acrobatic middle eight in front of a stadium of people.

I had no idea what the song was, but there was something about the effortless way she traversed the melodies that captivated me. There was an extra element, too; the video was annotated by vocal coach Jaron Legrair, whose positive feedback – “She keeps that mouth open and pretty wide … She’s not using a ton of air, though!” – and the stunned face smiling away in the corner added a collective sense of wonderment. Singing isn’t an Olympic sport, but it feels right sometimes to celebrate the gold medallists. Or even to celebrate anything at the moment.

I scrolled the comments – all positive, which felt weird – and found the apparently quite popular song was called The Only Exception (500m+ Spotify streams and counting), from 2009’s Brand New Eyes. I’d never really listened to Paramore aside from their bigger and brighter singles – Still Into You, Hard Times – but this love-is-the-only-thing-we-have epic has been on a loop ever since. When it crashes into that middle eight, all pent-up emotion cascading out, I scream along, imagining Jaron’s notes: “Wow, unspeakably unique!” Michael Cragg

Little Annie – Short and Sweet

A few years ago, I came across I Think of You by Little Annie, a gorgeous (and hilarious) take on a love song that recalls Tom’s Diner, but with a little more eroticism. It became a bit of a staple on my iTunes but for some reason I assumed it was a one-hit wonder – as many of the best tracks from the 80s and early 90s are – and didn’t think to look any further.

This year, though, I’ve unknowingly encountered dribs and drabs of Little Annie’s back catalogue through internet radio shows and YouTube suggestions. It took a while to connect the dots both because of her multiple aliases (she also goes by Annie Anxiety and Annie Bandez) and just how varied her back catalogue is (she has collaborated with artists as wide-ranging as Crass, Coil and Lee “Scratch” Perry).

Her 1992 debut album Short and Sweet, produced by dub legend Adrian Sherwood no less, shows off this range. It drifts between groovy, percussive house and floaty Balearic moments, with brief pit stops into darker, seedier territory. Give It to Me sounds like a Belgian new beat wrong-speeder with its heavy, acid-tinged synths and X-rated vocals. There are definitely some bargain-bin B-side moments scattered throughout the record, but even these, with their rudimentary electronics and corny lyrics (complete with backing vocals), are charming in their own right. Safi Bugel

after newsletter promotion

Mike Francis – Features of Love

Once a month, our very own Safi Bugel hosts a show on NTS as Babyschön, playing untold amounts of Belgian new beat and the chuggingest of sleazy dance chug. It’s the privilege of being part of the same music-swapping WhatsApp group chat that we can listen along and hound her with “track id pls” requests while she’s busy DJing: my Bandcamp and Spotify saves bulge ever more with every show, her selections are so rare and great.

One recent standout was Italian singer Mike Francis’s 1985 single Features of Love, which hits me right in my soft spot for wistful mid-80s pop: imagine if Orange Juice hailed from the Balearics rather than Bearsden, and were roped in to soundtrack a big-budget romance starring Daryl Hannah. (There’s also a good dose of Night Falls Over Kortedala-era Jens Lekman here.) The straightforward romance, too, is a tonic, the tousle-haired songwriter in awe at “the glow of love just flowin’ free / And full of tenderness”. Laura Snapes

Robert Palmer – Johnny and Mary

It’s narratively annoying that I can’t remember how or why this particular love affair began. Was I feeling some kind of way? Did it happen on shuffle? Did I seek it out after a particularly enjoyable film? Impossible to say, but one way or another, for weeks this summer, I was obsessed with the hapless love between Johnny and Mary.

Obviously I had heard Robert Palmer’s song before – but I had never really heard it: the pulsing bounce of the synth line coupled with the morose vocal, the story of Mary stoically waiting for Johnny to get his shit together. It seemed to grapple-hook into my shaky mental state at the time: an absolute heartbreaker but also a bop. It became a kind of crutch, drowning out the noise in my head with someone else’s problems, someone else’s melody, someone else’s noise.

After a few weeks of relentless repeats, my obsession fell away, but not before I had made Johnny and Mary my entire personality. At End of the Road festival as the summer waned, my friends were DJing the silent disco. I heard the opening drum beat kick over headphones and nearly melted into a puddle: they were playing it just for me. It felt narratively perfect to hear it that way – alone and surrounded by people, the camera zooming out from my beatific face as the credits rolled. She faced her minor problems and overcame them! The End! But then of course, life went on. And every so often Johnny keeps running around, Mary keeps counting the walls and, every so often, I pop it on again. And then again. Kate Solomon

Cher’s disco era

Cher’s discography has plenty of underrated nooks and crannies – to name a few, 1969’s 3614 Jackson Highway, a collaboration with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section; a glammed-out 1980 rock album with her band Black Rose; or the internet-only 2000 release Not Commercial. But in 2024 I discovered and embraced Cher’s brief (but polarising) disco era, represented by her LPs Take Me Home and Prisoner.

Released in January 1979, Take Me Home was a modest success thanks to glamorous dance hits such as the sizzling title track and effervescent Happy Was the Day We Met. But Cher cuts through the frothy discotheque glitz with powerful vocal performances, especially on the gospel-inspired power ballad Love & Pain (Pain in My Heart) and the funk-flecked rocker Git Down (Guitar Groupie). And Take Me Home ends with the underrated My Song (Too Far Gone), a subdued, folkish song Cher wrote about her crumbling marriage to Gregg Allman.

Prisoner, which was released later in 1979, was a commercial flop. The album deserved better, especially since it feels akin to the eclectic variety shows Cher herself acted in around this time. The deeply unserious Shoppin’ nods to vintage sock-hop pop and a Broadway showstopper; Boys and Girls is a Meat Loaf-esque theatrical rocker; and Holdin’ Out for Love is a twangy soul-pop number. But nothing compares to the over-the-top highlight Hell on Wheels. Deliciously campy – the lyrics hint at a red-hot romance using roller skating-related double entendres – the tune pairs bubbly disco-funk grooves with jagged electric guitars. Hell on Wheels is ripe for rediscovery – if not a modern dance-punk cover – but then so are both of these LPs. Annie Zaleski

Buffy Sainte-Marie – Helpless

When it comes to the enviable skill of being able to fully embody a cover song as your own, some artists are far better equipped than others. Folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie is one such artist. She sang with such forceful conviction that when I first heard her cover of Neil Young’s 1970 song Helpless, I was convinced it could only have been written by her. I mean, how could there be a time when Sainte-Marie wasn’t responsible for delivering the opening line, “There is a town in north Ontario,” in her bluesy, gut-busting howl? Another shock was the revelation that Sainte-Marie, who mainly wrote her own original material, only recorded Helpless for her 1971 album She Used to Wanna Be a Ballerina because her record label, Vanguard, was worried about low sales and wanted more contemporary covers to boost her audience.

Nevertheless, Sainte-Marie made her version her own. Where Young opted for a soft, reticent delivery, Sainte-Marie’s bold, soulful delivery etched an air of desperation into every lyric. She transforms the lilting folk song into a powerful gospel on the need to overcome, as she appeals to the listener: “Baby, sing with me somehow.” While my love for Neil Young will never die, when it comes to which version of Helpless I want to eviscerate my soul, he might have to take a back seat on this one. Stephanie Phillips

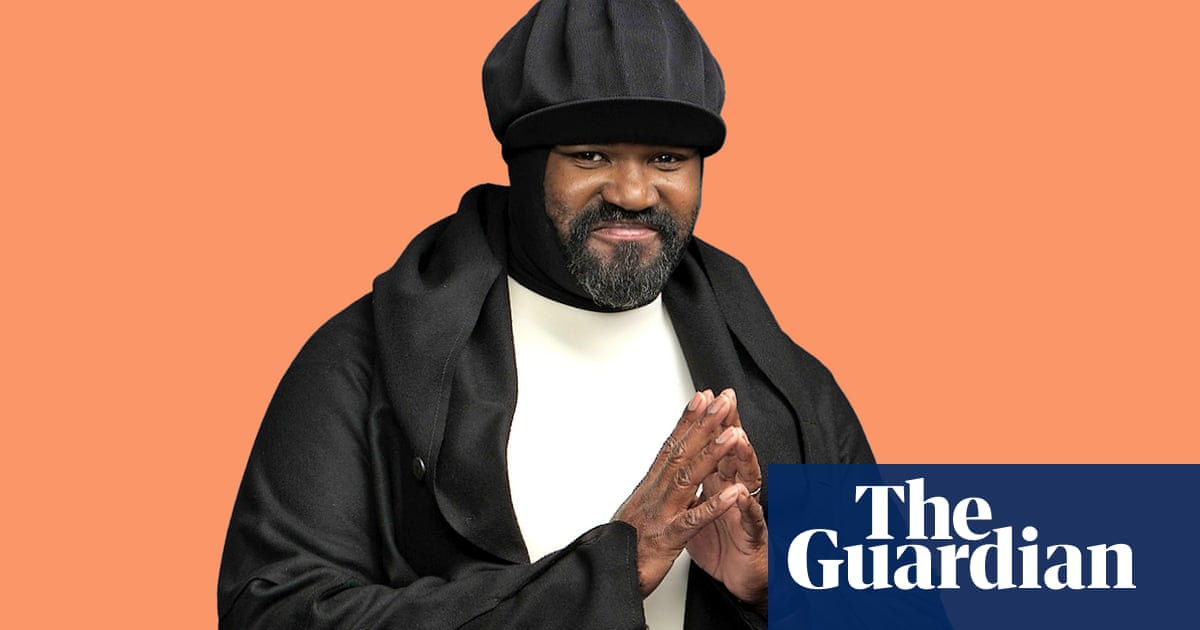

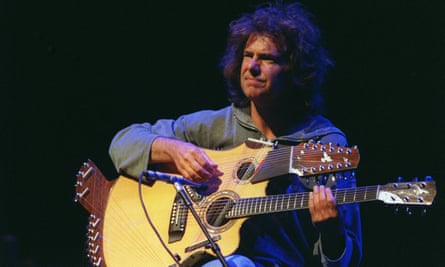

Pat Metheny – Dream Box

Jazz can be an overwhelming experience. Since most major bandleaders release at least one album a year, it can feel impossible to know where to start when you’re faced with dozens of records and re-recordings to choose from.

I had the good fortune to interview guitar virtuoso Pat Metheny earlier this year – a 70-year-old with more than 50 albums and 20 Grammys to his name. I knew about his early work, the lauded collaborations with bass pioneer Jaco Pastorius and his fusions in the 80s with the Pat Metheny Group, but there were swathes of his discography I had yet to cover. During my interview prep, I began hunting through his recording history, alighting on everything from the steel-stringed New Chautauqua record to the machine-made Orchestrion project, but it was 2023’s Dream Box that has since stayed with me.

For an artist known for playing a custom three-neck, 42-string guitar, Dream Box is a shockingly slight and nimble record. Across nine tracks of solo acoustic guitar, Metheny produces a masterclass in minimalism. There are the soft, sprightly melodies of opener The Waves Are Not the Ocean, the yearning romance of Trust Your Angels, the reverberating balladic chords of Clouds Can’t Change the Sky, and a hauntingly lyrical interpretation of standard I Fall in Love Too Easily. Over the past year, I’ve listened to the album when I’m writing, can’t sleep – or while I’m staving off sleep at 6am while babysitting my two-year-old nephew.

It’s a record that has been a constant background presence, but it is no wallflower – instead, Metheny’s late-career quietude is full of peaceful depth, the perfect entry point into his vast catalogue and a jazz remedy for our everyday chaos. Ammar Kalia

.png) 3 months ago

28

3 months ago

28