On a frosty bright-blue day in February 2024, Jeremy Deller was in Dundee, examining severed heads. “How can anyone not be fascinated by a head?” he said. Deller is an elfin figure, 5ft 5 on a good day, a low-key, unintimidating presence. The only giveaway to his identity as an artist was his slightly dandyish clothing: a KLF T-shirt, a checked neckerchief, lemon-yellow socks and a purple Missoni sweater, which he hurriedly explained, lest he come across as too fancy, he had bought on sale. When he won the Turner prize in 2004 he looked like a dapper schoolboy. Twenty years on, the only indication he was nearing 60 was the way he kept alternating a pair of reading glasses with his sunglasses, toggling them between nose and forehead.

Deller, carrying himself more like a journalist than most people’s idea of an artist, was questioning Dr Tobias Houlton, a forensic anthropologist from the University of Dundee, about the art and science of building 3D or digital impressions of a face from skeletal remains. On a trip to the university the previous summer, Deller had been fascinated by a re-creation of the head of Charles Edward Stuart, the “Young Pretender” who claimed the British throne in 1745.

He was now thinking about how he might work with Houlton or his students to create an element for a new public artwork, a celebration of the 200th birthday of the National Gallery in London. He was fascinated, he told me, by “the art, the craft, the uncanny nature of these reconstructions, the way they can rewrite how we think about ourselves and reorient us in relation to history. The National Gallery has lots of moments like this: lots of photorealist depictions of heads. Lots of severed heads.”

Deller has become so well-known that it is easy to forget the sheer oddness of his status as an artist who makes absolutely nothing with his own hands. His most famous works have not been physical objects, but large-scale public events – restaging the most brutal confrontation of the miners’ strike, say, or putting men in first world war uniform on the streets of Britain in 2016 to commemorate the battle of the Somme. Even artists who lean towards the conceptual tend to have had a fine art training, and possess some manual facility. But Deller was famously kicked out of his school art class aged 12 for incompetence, and went on to study art history, not fine art. (Emily Stone, the curator with whom he is working on his National Gallery project, showed me, with a barely suppressed giggle, one of his terrible drawings. It purported to show a person costumed as a neolithic standing stone, but, with its twiglike arms emerging from a lumpen shape, it resembled a child’s drawing of a snowman.)

In his ongoing project of excavating Britishness and Britain’s past, Deller seeks out collaborators, usually from fields far removed from the art world: synchronised swimmers, archaeologists, power lifters, brass-band players, army veterans or simply willing volunteers. This way of working relies on Deller’s manner and character: his genuine curiosity about the skills of others. Still, for all his punctiliousness at acknowledging those who have helped him, there is never any doubt about who is the creator, the artist. It is Deller.

His particular genius lies in his way of combining unlikely cultural phenomena – brass bands and acid house, say, or stone circles and bouncy castles – to illuminate a historical connection in a revelatory, often ecstatic way. In 2001, he had 1,000 volunteers – some civil war re-enactors, some ex-miners – recreate the battle of Orgreave, the most violent confrontation between pickets and police during the 1984-5 miners’ strike. Deller’s point was that the miners’ strike was a kind of civil war, fought, like its 17th-century precursor, with cavalry and infantry, if not pikes and muskets. Filmed by director Mike Figgis, the work has become so firmly part of the contemporary British art canon that it is hard now to recall how deeply unfashionable it was to be thinking about the miners’ strike just then: New Labour was triumphant, the economy was booming and grim industrial disputes were supposedly a distant memory. When Deller’s peers – the likes of Damien Hirst and other so-called Young British Artists – were making fortunes selling highly commodified works to Charles Saatchi in London, staging a performance about industrial relations in a windy field near Sheffield seemed an especially quixotic thing to do.

Later, in 2012, Deller came up with the idea of an enormous bouncy castle in the shape of Stonehenge, which anyone could come and bounce on (and did, in great numbers). “The biggest, stupidest artwork ever,” as he called it, began its life on Glasgow Green, before touring the UK and doing a stint outside the Grand Palais in Paris. The work, called Sacrilege, was not, however, stupid. In the year of the London Olympics, it was a wry way of expressing Deller’s hatred of organised sport. (Bouncing on a blow-up Stonehenge was just about as rational an activity as any Olympic event.) It was also a comment on the status of Britain’s most celebrated prehistoric site, once a place of gathering and ritual, now cordoned off as a revered, largely untouchable monument. And, as I can attest from experience, it was simply a lot of fun. The curator who worked with him to realise the project, Katrina Brown, told me that her daughter, then aged six, had adored it, and for years afterwards, when about to be dragged around yet another contemporary art exhibition, would say, “That’s all very well. But can I bounce on it?”

Deller’s celebration of the 200th anniversary of the founding of the National Gallery this year is perhaps his largest, and certainly his most complicated, public project to date. To mark this seminal moment in British cultural life, Deller is creating a procession along Whitehall and a large-scale event to take place in July right outside the gallery on Trafalgar Square. He is fascinated by the history of the square: a public space that has long been the scene of celebrations, protests and political rallies – with the museum itself the calm, serene backdrop. It is in these countercultural moments of near-violence – or elation, or joy – that he often finds something essential and otherwise inexpressible about Britain’s history or identity.

Deller wants the exuberant, chaotic spirit of many of the paintings inside the National Gallery to spill into the streets and the square: the humming activity of Bruegel, the anarchic, unruly scenes of Hogarth. He anticipates the event having something of the atmosphere of a medieval fair, or a fete or pageant, with sideshows and acts. No stage, he said: no hierarchy, no VIP area, no celebrities. When we spoke, he used the word “bacchanalian” a lot. He liked the idea of mythological stories escaping the museum to come to life in the open space. He frequently cited the 17th-century artist Salvator Rosa’s “amazing painting” Witches at Their Incantations, in which a group of naked women cluster round a corpse on a gibbet performing strange rituals and spells. The Trafalgar Square event will be called The Triumph of Art.

The London extravaganza will be preceded by four related celebrations dotted around the UK in Derry, Dundee, Llandudno and Plymouth, which will unfold in turn over four weekends starting in late April. Instead of being one idea wrought at large scale, as with some of his most ambitious earlier works, this project contained all the complexity of “about 100 things” made in five locations. When we spoke in early 2024 Deller was calm, but I could sense an underlying anxiety. Remembering his fears about the Somme piece, he said: “All it would have taken was one drunk person to punch someone in the face because they didn’t like the British army. With these events, you can’t control the weather. You can’t control anything or anyone.”

The work that changed Deller’s life came to him fully formed, “like an apparition”. It was 1996 and the idea that arrived by way of its neat, compressed title was Acid Brass, a performance work in which a traditional brass band performs arrangements of acid house tracks. At the same time there also came, “in a rush of ideas”, a handwritten diagram that connected, through a musical and political genealogy, old-school British brass bands, which were overwhelmingly associated with mining towns, and acid house parties, which usually took place in disused industrial warehouses. The diagram he called, modestly, The History of the World. Taken together, Acid Brass narrated, in compressed form, a story of 20th-century British history, from its industrial zenith to its post-industrial collapse and transformation.

Actually enacting Acid Brass – persuading a brass band to play acid house tracks – was a whole different matter. It was the first time that he had asked members of the public, with no connection to the art world, to collaborate on a project. When he wrote to the Williams Fairey Band, one of the most traditional and respected brass bands in Britain, he delicately referred to “contemporary electronic music” rather than acid house, since the often illegal parties had a bad reputation at the time. “I knew nothing at all about acid house music before I met Jeremy,” Rodney Newton, the band’s composer and arranger, told the BBC a few years ago. The ease with which the musicians took it on, though, was a revelation. It marked a shift in his career, Deller has written, from “making things to making things happen”.

The media, by and large, was hostile to the pretensions of contemporary art, but the public turned out to be much more open and curious. “The first time it was performed, in 1997 in Liverpool, students and young people came maybe for a laugh or to take the piss, but then when the music began they didn’t – because the music was amazing,” Deller recalled. “The band were top players. You can feel the air pressure change in a small room when a brass band begins to play.”

Acid Brass has been performed from time to time ever since – not least at the opening of Tate Modern in 2000. One chilly night last March, I took a friend to see it performed at Goldsmiths, University of London, by the Listening Project, a music collective. “No one turned away!” proclaimed the flyer, optimistically. When we arrived, though, the place was heaving, and harassed staff were trying quite hard to turn people away. The chairs that had been put out as if for a recital had to be removed to accommodate the audience, which looked like it contained some who had raved the first time around, along with a lot of students. As they pumped out Can U Dance and Voodoo Ray, the band seemed both shocked and delighted by the ecstatic crowd and the party atmosphere. As Deller wrote of the work in his 2023 book Art Is Magic, “a primal switch had been flicked”. Deller himself witnessed all this but inconspicuously, in a corner, and fled home, he told me afterwards, in time for Newsnight.

The idea for We’re Here Because We’re Here, the work that marked the centenary of the first day of the battle of the Somme, was similarly epiphanic. The notion of men in uniforms simply materialising, without advance publicity of any kind, in railway stations across the UK, came to Deller when he was on his bike in Holloway, north London, where he lives. “You spend the rest of the time trying to keep to the integrity of that idea, keep it whole and not have to compromise through the years of process and budgets and other people getting involved,” he said. The work was eventually realised with the help of 28 theatres and 1,500 volunteers dotted around the UK. “He is very friendly and open and clear,” said Rufus Norris, the former director of the National Theatre who worked with Deller on the project, and drilled many of the volunteers. “At the same time he has an absolute pure commitment to the idea. He has the slight distance of the observer about him.” The haunting presences of the young men – who said nothing to passersby, and if approached just handed over a card on which was printed the name of a man who had been killed on 1 June 1916 – captured the imagination of the public, spreading rapidly across social media. It remains, despite or possibly because of its evanescence, Deller’s most resonant large-scale work to date.

The Triumph of Art, the event for the National Gallery, is a very different animal from Acid Brass and We’re Here Because We’re Here. With its scattered locations, and its vast number of different elements, the idea is too enormous to appear in Deller’s imagination in one prophetic moment. To make it happen, Deller is working with Stone, a curator employed by the National Gallery for the purpose, and four assistant curators based in each of the locations beyond London – as well as an army of collaborators, including a synchronised swimming team from Plymouth, a group of female morris dancers from Stroud and a troupe of mummers from Armagh who perform in giant handmade wicker masks.

To begin to devise the events in the different cities, Deller has spent time in each, getting a sense of its communities, possible collaborators and locations. When I joined him with Stone in Dundee in February 2024, it was his second trip to the city, and things were still exploratory and open. Laura McSorley, the assistant curator in the city, had drawn up an itinerary of things that she felt might interest him, and we tramped around from appointment to appointment, taking in, aside from the re-creators of heads, an array of stuffed rats, ferrets and razorbills in the university museum stores; a Risograph in the art school (a low-tech way of printing colour posters, with a tactile handmade finish); and an unromantically urban neolithic stone circle in a scrappy park, with a bottle of Buckfast lying in its centre and an Asda superstore on the horizon.

At the end of the day McSorley took everyone to her favourite Dundee bar to watch a session of Scottish traditional music. Deller was exhausted by that point: tired out by listening and asking questions and being scrupulously polite. He observed the young musicians closely, seeing how they interacted and worked together, happy not to have to talk.

The next time I saw Deller and Stone, three months later, they were meeting the four assistant curators in a windowless basement room at the National Gallery for a progress report. What had begun as a series of fun, possibly unrealisable ideas, was beginning to harden into things that could actually happen. Deller had a rule for these meetings: there was to be no budget discussion while he was around. He’d work on the ideas; everyone else would work out how to pay for it. (He himself was being paid rather less than the average UK salary for his two years on the job.)

The assistant curator for Plymouth, an exuberant young man called Rhys Morgan, talked excitedly about the city’s art deco lido by the sea. “I’d love to do something Hogarthian there,” said Deller. “We need Herculeses, too,” he added, thinking of the extraordinary mythological bodies in Renaissance works upstairs. “We should get some bodybuilders involved.”

“We could have a contest for Herculeses, at the lido,” Morgan chipped in.

“Or is it a Hercules lookalike contest?” said Deller. “Then in the summer you could have strongmen and women in Trafalgar Square. We need strongmen-type people to pull things there. We need muscle.”

For Dundee, Deller said: “It would be good to have more than one severed head.”

“You have a whole folder of severed heads there,” replied McSorley, pointing to a sheaf of images from the gallery.

Later that day, the gallery put on a series of public events about Deller and his work. In one, he was in conversation with his longtime collaborator, trade union banner maker Ed Hall. They told the story of their first meeting: it was at the Lambeth Country Show in south London in 1999, when Deller saw Hall’s banner for Unison. At the time, Deller and fellow artist Alan Kane were building what they called their “folk art archive” – collecting creative work that came from outside the art world and was, in their view, much more interesting than what was going on in the mainstream. When Hall showed Deller pictures of all the banners he had made, “I felt I had discovered a folk art holy grail,” Deller said. He asked if he could borrow one for a show he was involved in, “and when he said the Tate would come round and collect it I almost fainted”, remembered Hall.

Hall and Deller’s public conversation took place against the backdrop of Piero della Francesca’s painting The Baptism of Christ. At one point, the bright, joyous banner for the union United Voices of the World, which represents low-paid, precariously employed workers, including museum security guards and cleaners, was held up for the audience to admire. “It was out on an industrial dispute recently,” said Hall, “and it looked great in the sunshine.” A Spanish-speaking woman, a member of the union, stood up and made a short and moving speech about the generosity of Hall and the struggle for workers’ rights in a hostile world. It felt like a moment – under the banners and the Piero della Francesca – that only Jeremy Deller could have engineered.

The restrained, scholarly world of the National Gallery may seem at odds with Deller’s fascination with British pop culture, but in many ways his presence among the paintings of the Italian renaissance made perfect sense. His education at the Courtauld Institute – the most respected centre in Britain for the study of art history – was essentially designed to make him a curator of old masters. (In fact the director of the National Gallery, Gabriele Finaldi, was both Deller’s classmate for school art history lessons and a fellow Courtauld undergraduate.) Deller appraises the world as an art historian: tracking resonances, finding connections. He watches TV news images, he said, as if they were paintings – “Is it Bruegel? Is it Hogarth?” The study of art history, he said, left him with an “incredible image bank”.

There is a photograph that has long obsessed him. Taken in 1973, it shows Adrian Street, then a champion wrestler, posing with his coal-stained, helmeted, bewildered-looking miner father at the pithead of Bryn-Mawr colliery in south Wales. Street is costumed like a glam-rock star: high-heeled snakeskin boots, metallic trousers, fur-trimmed cape, feather fan and full makeup. (The image inspired a 2010 film of Deller’s, called So Many Ways to Hurt You.) “It is as good as any painting in the National Gallery,” Deller said. “A piece of contemporary mythology.” As he pointed out, the photograph bears an uncanny resemblance to Holbein’s most famous painting, The Ambassadors. Street had started as a miner himself before becoming a high-camp wrestling star, and for Deller, the picture encapsulated Britain’s postwar shift from an industrial to a service economy, embodied in Street’s personal transformation. A single image that, for Deller, communicated a whole universe of historical forces and societal change.

Deller’s fascination with art history began when he was a teenager. Though from an ordinary middle-class family – his mother worked as an NHS receptionist and his father worked for Tower Hamlets council – he was sent to Dulwich College, a public school in south London. Nigel Farage was couple of years ahead; they didn’t know each other. The art history teacher was the late Giles Waterfield, the director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, a gem of a museum filled with old masters from Rembrandt to Rubens.

It was always clear, said his old classmate Finaldi, that the teenage Deller wanted to do things differently. For his sixth-form project, while Finaldi studied 15th-century masterpieces in Hampton Court Palace, Deller “went off to find Francis Bacon in Soho”. (In fact, Deller said, this was less a case of tracking the painter down in some drinking hole than plucking up the courage to speak to him at an exhibition in Mayfair.) While Deller was an undergraduate at the Courtauld, there was a random encounter with Andy Warhol at an exhibition opening, which led to his being invited back with the entourage for drinks in the artist’s suite at the Ritz. That glamorous, louche world seemed to hold intriguing possibilities, and Warhol, with his restless experimentation with forms from painting and photography to TV and magazines, remains a touchstone for Deller. “But then I had another two years of drawings and attributions and altarpieces,” he said. At the Courtauld, Deller specialised in the baroque and, said Finaldi, you could think of his work as carrying a strong baroque influence: “He is a big fan of Rubens – an artist who wants to involve you physically, emotionally and spiritually. He loves the big, participatory, all-enveloping work of art. And that is the invention of the baroque.”

After university Deller wasn’t quite sure where he fitted in. He was unemployed a lot, and got jobs in shops and galleries, where his lack of practical skill let him down. On his first day working at a gallery in Mayfair, he managed to scorch a Hockney print when trying to remove an auctioneer’s label from its reverse with a heat gun. He quietly slid it back into the storeroom shelves without telling anyone. Lacking an art-school training, there was no obvious way of becoming an artist. The YBAs had come out of Goldsmiths; he didn’t know them till later on, and they were on a completely different track, intellectually and imaginatively. He lived at home. His mum did his laundry. He is sure his parents worried about him but, he said, “it was a household in which conflict was never aired”.

In 1993, Deller put on an exhibition in his parents’ house when they were on holiday. They didn’t know about it until a decade later, when Barbara Deller happened to see, in a book of her son’s, “a picture of a toilet that looked remarkably like mine. I read on to realise that it was no coincidence – it was my toilet,” she wrote in an essay for his 2012 mid-career retrospective at the Hayward Gallery. Open Bedroom, as Deller called the exhibition – seen by just a couple of dozen people – contained some of the seeds of his later work: cheeky pop-music references, borrowed lyrics, transcriptions of graffiti from the men’s toilets at the British Library. A card was printed with the words, “Help me – I went to a single-sex school.”

It took Deller another three years to get to his turning point of Acid Brass. Along the way, he enrolled at a screenprinting class and made a lot of graphics that were somewhere between printed ideas and works in their own right – posters for fantasy exhibitions, for example. He still makes posters now, in collaboration with graphic designer Fraser Muggeridge. Many were exhibited at the Modern Institute in Glasgow in 2021. “Every age has its own fascism,” said one, quoting Primo Levi. Another, “Farage in Prison”. (Often his titles have a certain prescience – in 2019 he made a film, consisting of footage of pro- and anti-Brexit protests in London, called Putin’s Happy.) In 1994, he made a poster purporting to be an advert for a re-enactment of the battle of Orgreave. He never expected that, five years later, he would get to make it into a real thing.

Acid Brass, with its origins in a title and a diagram, was similar. “I think the posters are a way of setting ideas loose,” said Katrina Brown, the curator who worked with him on Sacrilege, the bouncy-castle Stonehenge. “You can write down ‘acid brass’, and it sparks something in people. But then, of course, when you get the opportunity to make it happen, it becomes this glorious third thing.” All these large-scale works – Acid Brass, The Battle of Orgreave, We’re Here Because We’re Here and Sacrilege – are acts of compressing history, which insist that certain things from the deep or recent past are really part of our present. But the act of compression also opens up something else, something mysterious and indefinable: a sense of ecstasy, of elation, or haunting.

For someone who creates joyful mass-participation events, Deller can be rather unsociable. Early this year, I took the train with him and Emily Stone to Plymouth, where they were checking in on progress for the event in the city. Normally, Stone told me, Deller is a restless travel companion: “Can’t sit still.” If there are fellow passengers making a noise, he’ll move rather than ask them to stop. (“He sends me furious WhatsApp messages instead,” his longtime partner, painter Tasha Amini, told me.) On our journey from London to Devon, our table of four was completed, part of the way there, by a flustered traveller who clearly wanted to share her travel drama; Deller looked as if he’d rather die than fall into conversation.

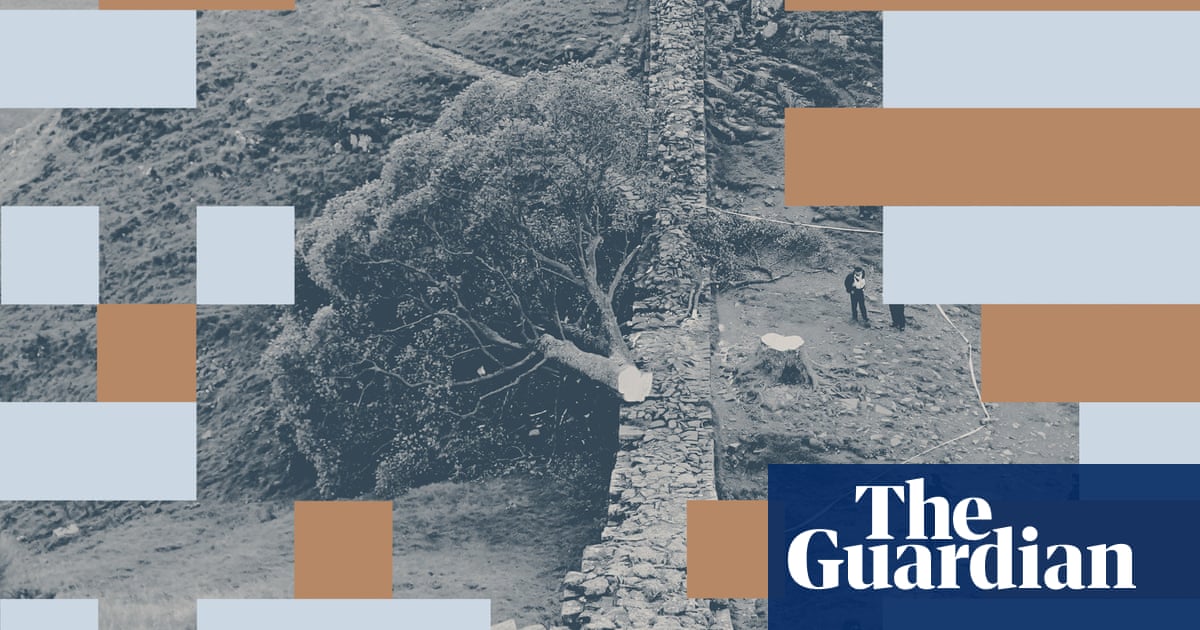

On arrival, after a pizza with the assistant curator in Plymouth, Rhys Morgan, Deller retired contented to his hotel room. He showed me his earplugs, custom made to fit his ears. He was calm, outwardly at least, about the upcoming events – the first, in Derry, was less than two months away. But he did sometimes wake up in the night worrying, he said. Most things were going to plan. There had been a hiccup with the severed heads in Dundee, and they were in the process of being remade. But it was all going to be OK.

The following morning, he, Stone and Morgan headed to the art deco lido, which had closed for renovation until the spring, the pool empty but for a few inches of brackish water. Deller was wearing a Lacoste anorak in cheery ice-cream colours and a pair of binoculars (“I always regret it if I don’t bring them”). As often, his outfit seemed to cross the divide between urban raver and sensible country walker. At the lido, they met two power lifters, Matthew and Leoni Tatman, who run a gym in the city. Matthew teaches fitness to marines, and Leoni was a medallist at last year’s Commonwealth Championships. These were two of the strong people who were going to take part in the Plymouth event. It was going to be called Hello Sailor! and the idea was to make it “very seaside, very bodily, very cheeky, slightly wrong in a good way”, Deller told me. “A kind of swimming-pool bacchanal. You hope it gets slightly out of hand.”

Deller and the Tatmans began to discuss practicalities. The idea drifted away from staging a competition – too long and complicated – into a strength display. “I like the idea of people not wearing much,” Deller offered, tentatively. “The old-fashioned strongman look.” The Tatmans said they knew plenty of male power-lifters who would be happy to go without a T-shirt. Talking to them, Deller had the knack of making everything seem ordinary and doable. He did not issue instructions or demands, but made suggestions and asked questions: there was no grand talk about the nature or the importance of the work. “He never tells anyone what to do,” said Jenny Waldman, who commissioned We’re Here Because We’re Here, the Somme commemoration. “But at the same time, it still ends up exactly the way he wants.”

After a visit to the Tatmans’ gym, full of torturous-looking equipment and motivational slogans (“There is no reason to be alive if you can’t do deadlifts”), Morgan drove me to the train station. He has a background in participatory, community arts. We discussed how distinct that world is from that of Deller’s art, despite superficial similarities. It reminded me of something Deller had said in a talk to students in Dundee: “Public art is often done to make people better, or make people feel better. But Orgreave was done to make people come up against history in a hard way – to make people angry.” The National Gallery celebrations were going to be a revel, a party, but there was a serious undertow. They were going to invoke ancient rituals and bring them into the present. They were going to suggest what it might be like to enact the mythological scale of many of the paintings in the museum – paintings that can seem safe and calm and neatly filed away as part of “art history”. It was another act of collapsing history, just as Deller had done with Sacrilege, the Stonehenge piece, or We’re Here Because We’re Here. “I wanted to make children cry,” he told me of We’re Here Because We’re Here. “I did, I wanted to scare children.”

Deller never takes part in these events himself. When the battle of Orgreave re-enactment was taking place, he slipped away to the edge of things: the event was on the verge of getting out of hand, he remembered, and he was worried about real violence breaking out. “For someone who tries to avoid confrontation and large groups of males,” he observed in Art Is Magic, “I certainly make a lot of work with these elements.” His loss of control on the day of his events – the way the public responds, the weather – is “both a liberating and stressful experience”, he wrote. On these occasions he finds himself feeling passive, entering an almost dissociative state. For The Triumph of Art, he predicted, “I’ll be terrified. I will be in the corner, just seeing what’s going on, or wearing a mask.” On the day of We’re Here Because We’re Here, 1 June 2016, I travelled with him from Waterloo station to Milton Keynes to watch the “soldiers” walk up the modernist avenues of the city and through its concrete shopping centres. He kept on the sidelines, observing events like someone who has invented a mechanism, cranked it up, and is anxiously watching it unwind.

.png) 1 month ago

29

1 month ago

29