Imagine growing up in a place where every stage of your life was framed by the best architecture of its day. You start out in an experimental elementary school, learning on a multi-level landscape of open-plan terraces connected by slides, before moving to a junior school where little towers of classrooms are linked by brightly coloured sloping tunnels. You spend your high school years in a heroic piece of brutalism, attend university in a sleek glass temple and go to church in a space-age tipi.

Your libraries, banks and even the local discount store are all the work of notable architects, and if your house is ever set ablaze, firefighters will come from a famous fire station, designed by a Pritzker prize winner. If you end up in jail, rest assured you will be incarcerated in a work of high postmodernism. And you may even die in a Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired hospital, then have your ashes scattered in the shadow of an Eero Saarinen-designed chapel.

Such a place exists – and it’s situated where you would least expect to find it. Set in the middle of the rolling agricultural plains of Indiana, a landscape dotted with “Farmers for Trump” billboards and White Castle hamburger outposts, the small city of Columbus makes for an unlikely modernist mecca. “Seldom, if ever, has so small a community contained so many examples of innovative architectural achievements,” declared the New York Times in 1970, noting that Columbus had been building at least “two masterpieces a year” since the early 1950s. Locals took to calling it “the Athens of the prairie”, and it’s a reputation the place has continued to uphold ever since.

The city’s many masterpieces, and the fascinating stories behind them, have now been brought together in a hefty tome, American Modern, authored by an architecture writer who grew up here. “I walked past the Saarinen church every day on my way to school,” says Matt Shaw, whose detailed text is accompanied by photographs by Iwan Baan, which celebrate the buildings as well-used backdrops to everyday small-town life. “My high school was actually part of the reason the contemporary architecture programme began,” Shaw adds, “because no one liked it.”

The programme he refers to was initiated by Joseph Irwin Miller, a wealthy industrialist and social reformer, who held an evangelical belief in the power of architecture to improve society. From the 1940s onwards, he worked to transform his family’s business, the Cummins Engine Company, into the world’s largest manufacturer of diesel engines, with $6bn in annual sales. To do so, he had to attract the best engineers from around the world, which, in turn, meant turning Columbus into the “very best community of its size in the country”, with the best schools, staffed by the best teachers, and the best civic buildings and parks, all built with the aim of “attracting good people to Columbus in all capacities”.

The plan wasn’t to turn it into a company town, like the Victorian paternalist visions of Bourneville or Saltaire in the UK. Instead, the city itself was the client, and paid for these public buildings as usual, but the Cummins Engine Foundation covered the architects’ fees – as long as they were selected from a list it provided, of the best designers of the day. “We believe nothing is more expensive than mediocrity,” the foundation stated, “and that good design need not cost any more than bad design.”

The architects were given at least a year to work up the plans, with responsibility for the building, interior finishes and furnishings, and recommending landscaping, “so that the building, inside and out is planned and designed in aesthetic harmony”. And if there was an extension planned to a building in future, its original architect would get first refusal – an almost unheard-of contractual perk.

The initiative was a clever ruse, not only to produce the best buildings, but to turn the city into a place where the top architects all wanted to work, each upping their game in the knowledge they would be judged alongside their best competitors. Columbus often managed to snag designers early in their careers, mindful that the more established celebrity names came with big egos and little patience. Frank Lloyd Wright was never on the list for this reason.

Walking around town, you find the results are as unexpected as they are varied. The public library – designed in 1966 by the Chinese-American architect IM Pei, who went on to build the glass pyramid at the Louvre – looks like a humble brick box. But step inside, and a powerful interior sequence unfolds beneath a concrete waffle slab ceiling, with reading areas placed at different levels around lush indoor gardens.

It stands across from a pared-back cubic church by Eliel Saarinen, father of Eero, built in 1942 as one of the first modernist religious structures in the US, with pews designed by a young Charles Eames. Pre-dating the Cummins Foundation’s architecture programme, it is the building that triggered the city’s modernist wave, and the first design that the young Miller influenced. Returning home from his studies at Yale and Oxford, he found his parents discussing the choice of architect. “Mother, I don’t see why you talk about a gothic church or an early American church,” he quipped. “We are not gothic or early American.” Mother was appalled. But the congregation went on to select the Finnish American modernist, setting the city’s progressive tone for the rest of the century.

A block away stands the low-slung Miesian pavilion of the former Irwin Union Bank, designed by the younger Saarinen in 1954, as a vision of democratic banking. It was intended to feel more like a welcoming country store than the usual fortress-like places of dark woodwork and tellers protected behind cages. It was a place of big windows and open counters, with a roof of shallow domes and a basketweave brick floor, intended to make farmers or factory workers feel comfortable walking in their mucky work boots. Complete with a drive-thru section, it set a new direction for postwar bank design, influencing thousands of branches across the country.

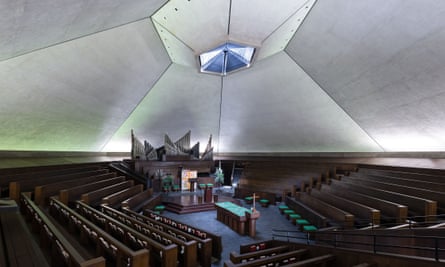

Two miles north, near a dream home he designed for the Millers, stands Saarinen’s other major contribution to Columbus. It couldn’t be more different. A hexagonal slate tent appears to hover above the grassy landscape, as if ready for take-off, rising to a pointed steel spire that shoots 60 metres into the air. Designed in the 1960s, at the same time that he was working on St Louis’s Gateway Arch and the TWA Terminal in New York, North Christian Church bears a similar level of structural ambition.

“When I face St Peter,” Saarinen wrote to Miller, pleading for more time to work on the design, “I [want to be] able to say that out of the buildings I did in my lifetime, one of the best was this little church.” He died suddenly, before it was completed, but he received his wish. The congregation has dwindled, but the building will soon enjoy a new, deconsecrated lease of life as an outpost of the public library.

These postcard sites are impressive and they provided photogenic locations for the 2017 film Columbus, in which they almost become characters in the story. But it is the public schools, dotted around the edge of the city, that show the true power of what the Cummins architecture programme could do. Often authored by architects who had worked for Saarinen, they show a real belief in the radical educational thinking of the 1960s and 70s.

From John Johansen’s zig-zagging network of colourful corrugated tunnels at L Francis Smith Elementary, to Hugh Hardy’s rainbow symphony of ducts and pipes at Mount Healthy Elementary, to the great space-frame roof of Paul Kennon’s Fodrea Community School, designed in collaboration with pupils (hence the slide, now sadly fenced off), they stand as physical manifestations of the progressive ideals of the time. Pioneers of their day, they would go on to influence a generation of open-plan learning environments.

“Columbus was not just about tasteful mid-century modernism, as some people assume,” says Shaw. “It was also about using the best ideas around global technological progress to deliver on the promise of a better world.” And these school buildings didn’t cost any more than the usual kind. They were often cheaper.

Miller died in 2004, and subsequent years haven’t spawned quite such exciting results. Projects have gone to big corporate firms, like Perkins & Will, Pelli Clarke Pelli and Koetter Kim, rather than untested names. But a recent shortlist to design a new air traffic control tower at the airport cast a wider net, and was won by the Arkansas architect Marlon Blackwell, suggesting a new direction. The Landmark Columbus foundation, which commissioned the book, also organises a biennial architectural festival here, Exhibit Columbus, which brings a diverse cohort of architects to town and helps to raise awareness of the city’s heritage, encouraging its current custodians to aim high.

At a time when a second Trump administration threatens to revive its neoclassical diktats for federal buildings, the Columbus model shows just how important it is for cities to fight for the best public architecture of our time.

.png) 3 months ago

30

3 months ago

30