Leticia Pinheiro grew up hearing stories about the Acari River. Her grandmother bathed in its clean waters; her father caught frogs on its margins; and many in the community made a living from fishing there.

Now, Pinheiro, 28, and her peers do not even call it a river; it’s become known as a valão – an open canal for sewage and rubbish. It borders the Acari favela, which spread over swampy terrain in northern Rio de Janeiro from the 1920s.

Floods after heavy tropical rains are historically a problem for this community. But as extreme weather makes them worse and more frequent, the river is increasingly seen as the culprit. In January last year, there was an unprecedented flood, when its waters invaded the homes of 20,000 people.

“When it floods, the whole Acari complex is affected. Rain brings huge anxiety, and people see the river as something extremely negative,” says Pinheiro, a member of the Fala Akari Collective, a community group.

The repeated tragedies have led residents to build their homes higher so they can live on upper floors and use brick or concrete to build bed bases and wardrobes to avoid losing furniture to the next floods.

The experiences of the Pinheiro family, past and present, are part of the myriad memories revived by an exhibition in a community museum in the Maré favela.

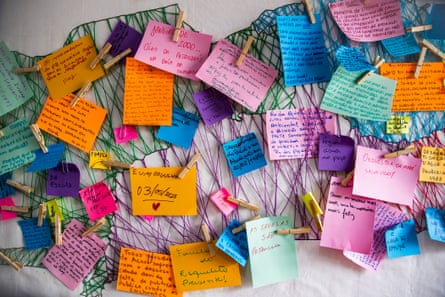

Favela Climate Memory brings together testimonials and historical data looking at how residents from 10 favelas in Rio relate to climate and nature, based on stories told by more than 400 people of all ages in conversation circles held over recent years, and discussing how they view and are responding to the climate crisis.

Organisers see documenting these memories as an instrument for climate justice in Rio’s favelas. Here and around the world, informal settlements such as Akari are disproportionately affected by global heating and extreme weather events due to compounding challenges such as poverty, overcrowded and poor-quality housing, disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards and pollution, gang and police violence, and restricted access to basic services.

Theresa Williamson, a Rio-based town planner and environmentalist, says: “Memory is essential to solving the climate crisis because belonging gives people a sense of identity and connection to their territory.

“When you know the environment where you live – the soil, the trees, the shared history – you care about that place. You have a sense of commitment.”

Williamson, who is half-Brazilian, has spoken up for favelas in Rio for more than 25 years. In 2000, she founded Catalytic Communities to promote the development of favelas. In 2018 the organisation launched the Sustainable Favela Network, which is behind the exhibition and includes members from more than 300 favelas fighting for climate justice.

“Favelas are not temporary slums,” she says. “They are consolidated communities that have been around for generations and where much of the culture associated with Rio was born, like the carnival, the city’s informality, the passinho dance.

“These communities are here to stay. When will we give them the infrastructure guarantees and the basic rights they are entitled to and address the historic inequalities that become so visible in this exhibition?”

The exhibition’s timeline portrays how the climate and environment are interwoven with these communities’ histories, showing how people have transformed their surroundings, how their precariousness made them prone to climate disasters, and how the authorities repeatedly used these events as an argument to push the favelas’ residents to the city’s margins.

Banners, pictures and news headlines in the show will remind visitors of historic tragedies in Rio, like the “flood of the century” in 1966 and another the following year, which killed hundreds of people and left 50,000 people without shelter.

They also portray how the city’s development has relied on the working poor without providing proper living conditions for them. Acari and Maré grew in the 1940s, when workers arrived from across Brazil to build Avenida Brasil, the city’s most important highway, and settled around the construction sites.

Informal settlements started to grow on Rio’s hilltops after slavery was abolished in 1888, and formerly enslaved people had nowhere to go. In the decades thereafter, waves of immigrants across Brazil arrived in the then-capital looking for work and opportunity, leading to these working-class communities multiplying.

Today, favelas are home to almost one in five residents in Rio. Nationwide, they account for 8% of Brazil’s population – about 17 million people. Most of the favelas are in cities, with 84% having a water supply and three-quarters having some form of sanitation, according to the 2022 census, compiled by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IGBE). These communities were referred to as “subnormal agglomerations” by the IGBE until only last year.

Despite the official view of favelas, the exhibition has showcased the strength and potency of these areas, with residents and community leaders travelling from across Rio to gather for the openingat the Maré Museum.

Representatives of each community gave moving accounts of hardships and resilience, revealing a shared history that many from communities spread far apart had not yet grasped.

Marli Damascena, 64, recalled the fishing community that used to thrive in Maré, where she was born and bred.

When she was a little girl in the 1960s, she had a view of the immense Guanabara Bay from the window of her home – built by her father, a migrant from the north-eastern state of Ceará.

after newsletter promotion

One day, the sea disappeared when landfill was used in the bay to push back the waters. This allowed social housing to be built in order to relocate residents of the precarious shacks on stilts built over the muddy mangrove margins of the bay.

“I saw that sea being filled in as a child, but it seemed normal. Looking back allows us to realise the drastic changes we went through and how strongly we were affected,” says Damascena, who co-founded the Maré Museum.

Maré means tide, and the venue includes a real-size replica of one of its palafitas, the houses on stilts that for years shouted poverty and inequality to those driving past on the way from Rio’s international airport.

Leonardo Souza’s mother lived in one of those houses. But she was not lucky enough to be relocated within Maré itself. Along with about 400 families, she was moved nearly 40 miles (60km) across Rio to Antares, where Souza grew up, in the western Santa Cruz neighbourhood.

In the project’s memory circles, Souza was touched to hear other residents recounting that period, which was traumatic for his parents, who were migrants from north-eastern Brazil. His father went from a five-minute journey to work to a two-hour commute each way every day.

“These policies were motivated by social cleansing – authorities wanted to show visitors a beautiful city and to hide poverty,” Souza says.

Antares first began to be occupied in 1975, although many of the promised brick and concrete houses were still unfinished. As residents from other favelas were relocated there and families multiplied, the community grew in a disorderly manner.

Wooded areas became deforested as it expanded, riverbanks were built on and became more prone to flooding. As the growing favelas cleared Santa Cruz’s wooded areas, the neighbourhood became one of Rio’s warmest districts.

“Santa Cruz is known to have Rio’s highest temperatures, but the memory circles reminded us of days when it was fresher,” says Souza, who recently planted 1,000 trees in the community with government funding in an effort to ease the stifling heat.

Today, he is a history undergraduate striving to reconstruct the community’s past. The exhibition involved partnerships with residents like him, as well as community museums, to revive “climate memories”.

Environmental devastation and risks are part of the history of informal settlements. Deforestation has historically accompanied the growth of favelas, as has the pollution of watercourses due to a lack of sanitation, proper waste disposal and tragedies caused by floods and landslides. Organisers note that these issues have long demanded public investment in response.

“It’s counterproductive to criminalise a huge portion of humanity because they are addressing their basic need for shelter by living informally,” says Williamson.

“There is no reason these communities couldn’t be upgraded and integrated into the city – not investing in them is policy,” she says. “Neglect is policy.”

According to the UN, nearly a quarter of people in cities around the world are living in informal settlements, and this urban population is expected to reach 3 billion people by 2050. Williamson hopes that the historical data in the exhibition may fill a critical gap in a context where climate policies tend to focus on biomes such as the Amazon rainforest or the Pantanal wetlands – but can rarely rely on data from poor urban settlements.

Memory is also a form of resistance. “It’s a way to denounce the systematic erasure of our history as part of our commitment with what comes next,” says Pinheiro.

This is especially important now, with her community facing another form of erasure because of the climate crisis. “Successive floods are leading our families to lose their photographs, documents and belongings,” she says.

“Climate change imposes many losses, not just the material ones.”

.png) 6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2