When writing about the hot, dry Santa Ana winds and how they affect the behavior and imaginations of southern Californians, Joan Didion once said: “The winds show us how close to the edge we are.”

I’ve lived here my entire life. I evacuated my family’s hillside home as a teenager. I’ve experienced the surrealism of watching ash rain down from the sky more times than I can count. But there is something different, supercharged, about the hurricane-force winds that fueled this week’s catastrophic wildfires in Los Angeles.

We’re not just close to the edge. It feels like we’ve already gone overboard.

Over 10 million people live in LA county – more than the populations of most US states – and 150,000 of them remain under evacuation (another 166,800 residents are under evacuation warnings). At least 11 have died, more than 10,000 structures have been damaged or destroyed and hazardous smoke is compromising our already compromised air quality. The Los Angeles wildfires are on track to be the costliest in US history with some analysts projecting economic losses of $50 to $150bn.

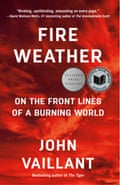

Writer John Vaillant, an American and Canadian dual citizen who resides in Vancouver, is intimately familiar with colossal fires like the ones devouring Los Angeles. He’s the bestselling author of Fire Weather, a gripping account of Canada’s 2016 Fort McMurray fire and the relationship between fire and humans in a heating world that was a finalist for the Pulitzer prize and the National Book Award.

Throughout his work, Vaillant is clear about why these “21st-century fires” are so different from the ones I grew up with: it’s the climate crisis.

I spoke to Vaillant about these new fires we’re seeing, not just in Los Angeles, but in Paradise, California, and Maui, the role of the fossil-fuel industry and his advice for Angelenos right now.

We don’t know who or what exactly started the Los Angeles wildfires but what role has the fossil fuel industry played?

It’s certainly not the cause of the fires, but it is an enhancer, an enabler and an energizer of the fires. I coined a term in Fire Weather, which is “21st-century fires”. It burns fundamentally differently than it used to, and it’s responding to climate change and the atmosphere’s growing ability to hold heat at low elevations and heat everything around us. Climate science ain’t rocket science. When you make things hotter and drier, they burn more easily. We have basically tweaked nature, pissed it off and we have altered the climate of this planet in a way that makes it more hostile to our ambitions and safety.

How do you connect Canada’s 2016 Fort McMurray fire, which you documented extensively in your book, to other massive fires like we saw more recently in Paradise, Maui and now Los Angeles?

The intensity of the fire that burned through Fort McMurry in 2016, in the sub-Arctic of Canada when there was still ice on the lakes, burned basically the same way as the ones in LA. You had the drought, you had the fuel, you had the wind and that’s all you need. That can be recreated anywhere in the world. Any city can burn now. LA is effectively surrounded by fires and the wind will decide the fate of LA. That is a weird situation to be in, but it’s also a very honest one. I don’t care what business you’re in, nature owns 51% of it, at least. We act as if we own it. We share it. That’s what LA is discovering.

In your book, you propose that we replace the nomenclature homo sapiens with homo flagrans, which loosely translates to ‘burning man,’ to characterize our species. Why?

Homo sapiens, which is a generous name for us, means wise man, rational man. We have speech and we can organize and do incredible things and that’s awesome. Flagrans means fiery, it means outrageous. We are fiery, we are passionate, we do outrageous things, good and bad. So flagrans is not necessarily negative, it’s not homo horribilis, but it’s recognizing our allegiance to and entanglement with and dependence on combustion. We are a fire species. Fire is our enabler and it’s our superpower.

When you look at how we live, and what drives the life we live, we are a fire-based society. I’m watching cars just whispering along right now. There’s no smoke, there’s no fire, but there are raging violent explosions going on under the hood of these gasoline-powered cars. If you were to mount an engine on your kitchen table and run it, you’d go deaf from the noise and then you’d be dead from the emissions if you didn’t have the windows open, so that’s what we have under the hood of our car. You multiply that by every furnace, every water heater and when you look at the things in your house, everything is mediated some way through fire’s energy or fire’s heat.

We need to tip our hats to the engineers because that you and I can sit in a car together and have a conversation with that incredibly powerful engine banging away under the hood, but so expertly muffled and insulated and siphoned off that we don’t hear it, smell it or notice it. The engineering has enabled us to forget the real cost, which is the heat and emissions. They’re invisible to our eye, but the atmosphere knows and fire absolutely senses it and is capitalizing on it.

More people are waking up to that cost it seems.

Fire has no heart and soul; all it wants to do is grow and expand. There are analogies there if you look at how Amazon behaves or Elon Musk behaves or Walmart. The emphasis is on growth and it’s exciting to grow a company and have an idea that sells. But the act of creation can also be an engine of destruction. The dynamic with the shareholder engineers the conditions for institutional sociopathy. The CEO’s job is to create profits for the shareholders to keep them invested. You have to do that at all costs. Profit trumps everything else and that is sociopathic and it’s not reality-based because it doesn’t take into account the limits of nature and the limits of nature determine whether we live or die or prosper or fail and that’s the reckoning.

What role does the modern house play in intensifying fires like the ones in Los Angeles?

I’m walking around on a laminate floor made from petroleum distillates, so if that started burning it would start offgassing and it would make terribly toxic black smoke. I’m leaning on a sofa, this colossal sectional that’s completely synthetic. Synthetic is almost a euphemism for petroleum protects. I’m sitting on a couple barrels of gas here, but it’s disguised as pillows and cushions and it’s really comfortable. The TV is all plastic. The kitchen cupboard doors are particle board, held together with glue, which is flammable chemicals. A particle board door is going to burn very differently than a pine covered door from your great-grandmother’s house.

What would you say to political leaders and billionaires who put the blame for these fires on Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass or Governor Gavin Newsom?

Unfortunately, we have the most powerful people in the world trying to distract and obfuscate and frankly lie about this. The idea of leaders lying about science is so fundamentally wrong and damaging and civilization-corroding. What do you do when the future president of the United States attacks the most populous state in the union? Using every opportunity to foment division and partisanship is absolutely toxic – as toxic as supercharging the atmosphere with fossil fuels that make the entire world more combustible.

You have a whole bunch of people who are traumatized now. When you go back and see the place you live, or where you were raised, or where you raised your kids, and you see that smoking ruin and somewhere in there is your kid’s bed, that is a blade to the heart and that’s what any national leader, industrial leader should be focusing on.

What can people do to better prepare for fires in the future?

We need people to speak courageously about why we are in this situation and our role in it, but we don’t have the same control as a CEO does. We don’t have the same control as a city councilor who got installed by the petroleum industry to advocate for petroleum. There’s a program in Canada called FireSmart where firefighters come to your community and go over your yard and cul-de-sac and suggest cutting things down and pulling things back. They recommend removing things that are fuses for fuel.

We’ve moved back into the forest because it’s gorgeous to live there. The Palisades is the poster child for beautiful mountain forest living, but it’s flammable as hell, especially in a drought. We have to get humble and renegotiate our relationship to fire and also to water and petroleum. How do we keep you safe and conscious where you live?

What’s one piece of advice people in the Los Angeles area can use right now?

Don’t look at the fire, look at the wind. If the wind is blowing over you, it means the embers are, too. The fire could be two miles away, but if the wind is toward you, the embers are, too, and act accordingly.

.png) 3 months ago

40

3 months ago

40