There is a series by Peter Hujar in which the photographer shot groups of friends, collaborators, lovers and other members of the New York avant garde, from the 1960s to 80s. In one image – including the artists Paul Thek and Eva Hesse – the writer Linda Rosenkrantz stands near the centre. “That was mostly people that I had gotten together, some who became very well-known,” Rosenkrantz tells me by phone from California. “Five or six of us would go ice-skating or dancing on Friday nights.”

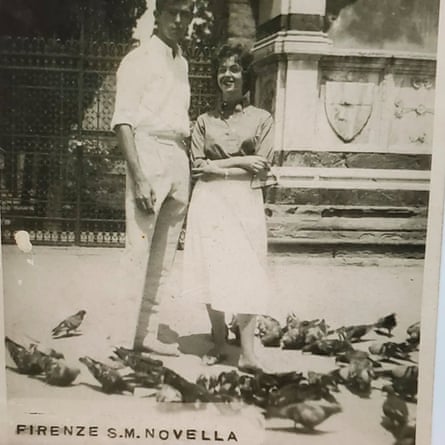

Rosenkrantz grew up in the Bronx in the 1930s. After university she moved to Manhattan to work in the publicity and editorial department of the Parke-Bernet auction house, becoming enmeshed in the city’s art scene. “I met Hujar in 1956. We hit it off immediately,” she says. Hujar and Rosenkrantz remained close until his death from Aids-related complications in 1987.

In the 70s, when Rosenkrantz was an established writer, she asked various artists to note everything that happened to them on a specific day, and then read it out for her to record. The first two were Hujar and the painter Chuck Close . The latter’s day – 18 December 1974 – featured a job photographing Allen Ginsberg for the New York Times.

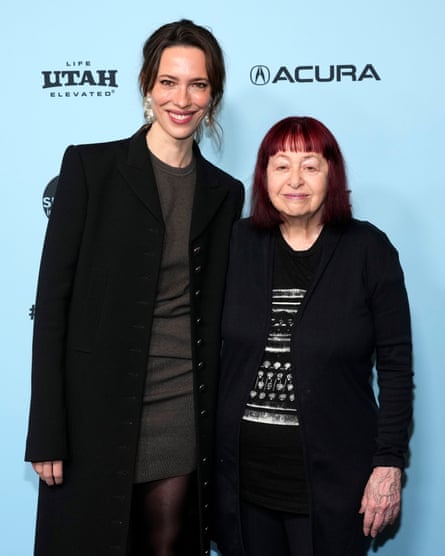

The project eventually ran out of steam and Rosenkrantz didn’t give it much thought until decades later, when Hujar’s archive went to the Morgan Library in New York and she donated the material. Eventually the publisher Magic Hour Press discovered it and in 2021 released their discussion as the book, Peter Hujar’s Day. Now it’s been adapted into a film by Passages director Ira Sachs, with Ben Whishaw as Hujar and Rebecca Hall playing Rosenkrantz.

“When Ira Sachs signed up for the film, he got in touch and I instinctively felt that he was the right person to do it, because I had liked his other films,” says Rosenkrantz. “It’s been a great experience for me, and it was so serendipitous.”

The film, which premiered to good reviews at Sundance, is due for release later this year. It plays into a recent surge of interest in Hujar, with an acclaimed show at Raven Row in London, after an exhibition at the Venice Biennale last year. While Hujar has been celebrated in the decades since his death, Rosenkrantz remains lesser known.

Aged 90, she is living in Santa Monica in California. Her husband of 50 years, the Guernsey-born writer and artist Christopher Finch, died three years ago. When I contact Rosenkrantz about an interview, she cautions that she’s not very articulate, which is ironic given how heavily speech features in her work.

She is best known for the cult book Talk from 1968, a dialogue-only “reality” novel, in which she spent months taping her conversations with friends. She then transcribed hours of tape into 1,500 pages of text, eventually whittling it to a story of three friends in their late 20s, spending a summer by a Long Island beach.

It was a raw, funny book presenting people from the Warholian art crowd talking about sex, drugs, psychoanalysis and much else. (Sample chapter title: Emily, Marsha and Vincent Discuss Orgies).

The book captured the modern moment in a novel way. “That kind of thing was in the zeitgeist. Artists were painting from photographs,” she says. “It just struck me as I was getting ready to go to East Hampton that I should take a tape recorder and I always had it in mind as a book.”

It caused a minor stir. New York magazine ran two reviews, alongside a photo of Rosenkrantz on the beach in a bikini, tape recorder by her side. Not all responses were kind. “It was mocked for all the talk of sex, drugs and therapy. There was a minister or some church person in Britain who thought it should be banned,” she recalls.

It had its admirers too; Harold Pinter sent a note of praise, George Romero’s production company wanted the film rights and Leonard Cohen was a fan. “He said that he had read it out loud walking on the beach,” she says, “and that he had tried to do something similar and decided that it couldn’t be done and that I had done it.”

Through the 60s and 70s, she was an art world insider, encountering the likes of Susan Sontag and David Hockney, going to Andy Warhol’s parties at the Factory. While working at Parke-Bernet, then acquired by Sotheby’s, she set up and edited their art magazine.

She met her husband while running the magazine. He was a friend of Chuck Close and later she was the subject of one of the painter’s large-scale portraits, not that sitting for him was particularly dramatic: “He took a polaroid. It was very quick and not a lot of talking or direction.”

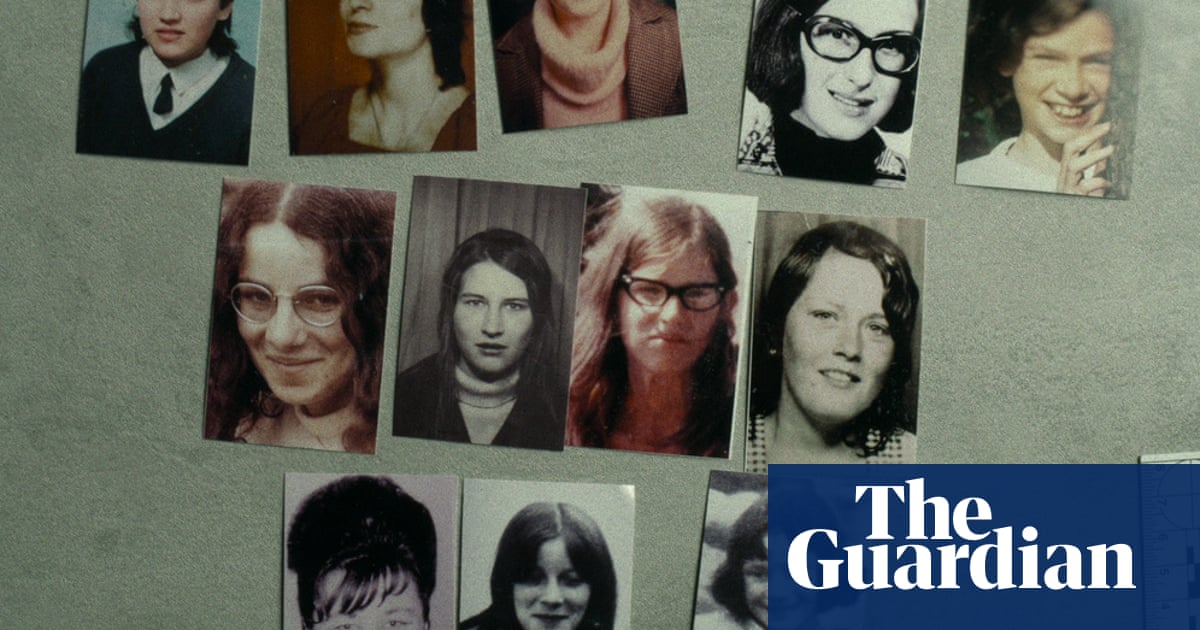

After Talk was published, she tried more tape experiments, including the day-in-a-life recordings, while another idea, Ex, had gallows humour: “I invited, one by one, about a dozen ex-boyfriends to dinner and taped the whole evening, and they’re pretty funny.”

after newsletter promotion

Rosenkrantz and Finch were inseparable. They co-wrote a novel called Soho, a multi-generational saga set in the Manhattan neighbourhood, and Gone Hollywood, a social history of cinema’s golden age. “We worked very well together,” she says, though Soho – written under the pseudonym CL Byrd – “did not make an impact.”

In 1990, the couple and their daughter Chloe left New York for LA, shortly after Rosenkrantz started a new track. A friend, Pamela Redmond Satran was an editor at Glamor magazine: “I pitched the idea of doing an article about baby names. And she said, ‘You know, I think this could be a book’.”

Before this, there were just books with lists of names; Rosenkrantz and Satran added more analysis with social context and trends. “The first one, which was called Beyond Jennifer and Jason, sold very, very well,” she says. This was followed by nine more books. They set up a website, nameberry.com, to collect everything. “It influenced the culture in a major way.”

Whether anticipating the babynaming industry, or developing new approaches to storytelling, Rosenkrantz always had a knack for the new. “My father used to say that I was ahead of my time when I was quite young,” she says. She has also “always been attracted to unusual forms”, which led her to publish a memoir in the style of a listicle, before they were BuzzFed to death.

My Life As a List: 207 Things About My (Bronx) Childhood was published in 1999. But by the 00s, her most significant work – Talk - was no longer in wide circulation. One reason for its muddled reception was that her publishers presented it as a straightforward novel, rather than a recorded rendering of reality. But in 2015, when New York Review Books revived Talk in their Classics strand, she says, “It was a complete reversal. It got great reviews and was seen for what it was. I kind of insisted that it had to be what it was meant to be, which was a taped book. I felt very redeemed.”

The book was praised as a blast of 60s counterculture and for its prescient view of neurotic city dwellers. Critic Becca Rothfield wrote that it “reminds us that wry self-awareness and anxious fragility are hardly a millennial invention”. It was seen as presaging the autofiction boom of the 2010s and likened to the TV shows Girls and Broad City.

Then in 2018, Lena Dunham’s website Lenny Letter revived parts of the Ex project: publishing transcripts of Rosenkrantz’s boyfriend dinners, rendered in comic strip form.

Today Rosenkrantz wants to do more with Ex, and revisit diaries she kept years ago. When Peter Hujar’s Day was published, she was said to be working on a book called Namedrops Keep Falling on My Head, about the people she’s met through the years. She says now that it’s not enough for a book but perhaps it will appear in another form. It takes in everyone from Janet Malcolm, David Hockney and Fred Astaire, to the beat poet Gregory Corso with whom she had a relationship. Meanwhile, she hopes the new film prompts interest in a screen version of Talk. “It has real scenes as opposed to the Peter Hujar [book].”

How does she feel about Rebecca Hall’s representation of her in Peter Hujar’s Day? “I’m very happy with it,” she says. “Most of it is Peter talking, but she doesn’t get to say very much, or I didn’t say very much. But she sort of captured the way I would have responded.” This hints at a self-effacing matter-of-factness to Rosencrantz. She doesn’t give off a sense of thwarted ambition or great regrets – just a life lived well.

In the original Peter Hujar transcript, there’s a moment where Rosenkrantz explains her motive for the project: “To find out how people fill up their days, because I myself feel like I don’t do anything much all day.” The fact that at 90 she’s still developing work seems to prove otherwise.

.png) 5 hours ago

5

5 hours ago

5