The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder – or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” – who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives.

She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative.

My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry that it’s not much fun to be around, and may be working against me in my personal life. What I experience as an even, nuanced discussion about the new Bridget Jones film, or the works of Joan Didion, friends will sometimes remember as a heated debate.

I wanted to know if I could objectively measure this “grumpiness”. Personality testing is a notoriously inexact science (and in the case of the Myers-Briggs, scarcely a science at all). But the so-called “big five” test is considered the most robust. It assesses agreeableness (including empathy, cooperativeness and social skills), openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion and neuroticism: together summarised as “Ocean”.

When I took a free big five test online, the results were as I’d suspected. My highest ranking was 81 points for openness; by contrast, I scored just 33 for agreeableness.

Does that mean I’m doomed to be disagreeable? Or can I change who I am?

Journalist Olga Khazan has bad news for me. “Agreeableness is the toughest one to change,” she says.

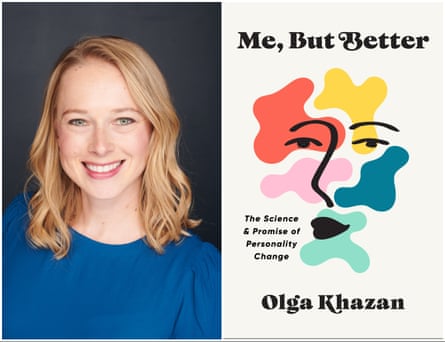

Khazan, a staff writer at the Atlantic magazine, should know. She spent an entire year trying to change her personality – documented in her new book Me, But Better.

Having recently decided to start a family, Khazan recognised that her flinty, lonerish tendencies might not serve her well in motherhood. To increase her extraversion, she took improv comedy classes, forced herself to throw parties and attended MeetUp groups of like-minded strangers.

In the process, she discovered that personality was not a consistent, immutable truth. “You have certain proclivities, but it is flexible – you do evolve over time, and if you want to change, you can change even faster,” she says.

Even genetic factors aren’t impervious to the environment. Attending university, for example, can foster openness as it exposes you to new ideas, different people or opportunities to travel.

Two factors seem particularly pertinent to tweaking your personality, Khazan goes on. “One is mindset: ‘I would like to be like this, and I believe I can change.’”

The other is follow-through – “you have to actually do the behaviours associated with the new personality trait”.

To some extent, personality change is about faking it ’til you make it, Khazan says: there’s no bigger secret than “go out and do it, for the rest of your life”.

With time and repetition, improv, socialising with strangers and otherwise extending herself became easier. “It doesn’t necessarily feel like eating your spinach and running a marathon every day – it starts to feel more like just what you would like to do.”

It’s not that there are bad personalities, or that you should aspire to a total overhaul, Khazan adds. But if we stick with easy, instinctual or habitual behaviours, we may sell ourselves short.

“We tend to, over time, fall into patterns and habits that could use an update – to put it mildly,” she says.

Now a parent, Khazan’s experiments in extraversion are paying off. “I’ve had a totally different approach to motherhood than I think I [otherwise] would have,” she says. “I’ve really made it a point to join new mom groups, reach out to other new moms and cultivate new-mom friends.”

Before her personality-change project, she would probably “have tried to white-knuckle it”, Khazan says. “‘I’m not a joiner,’ ‘I don’t need these other people,’ ‘I’m not like other moms’ – I would have had more of that mentality.”

after newsletter promotion

Such “limiting beliefs” about ourselves are often at the root of our disagreeable behaviours, Khazan writes. When I voice all the flaws I identified in a film, for example, it may come from a desire to express myself authentically or prove that I was engaged.

Cultivating curiosity for what my friends thought could be a small step towards developing agreeableness, suggests Khazan. “You could still hang on to those thoughts, and that skill of analyzing things really closely, but you could also start to mention some things you did like, or get interested in why the other person liked it.”

But every group dynamic is different, Khazan adds, kindly: some friends might be accepting of my critical tendencies, even appreciative. “That part of you might not need to be changed … Not everyone is for everyone.”

Often people mistake agreeableness for being a chump or a pushover – “just doing whatever everyone else says”, says Khazan. But it’s more about social skills, including picking your moment and knowing your audience. It’s arduous work but worthwhile, Khazan suggests.

People who rank high in agreeableness are happier, less likely to get divorced, have a high quality of life and are more resilient to adversity. People who rank lowest are generally psychopaths. I scored 33 points, not 0 – but I know what direction to be moving in.

Many people seek to change their personality to make themselves more likable or gain others’ approval. But there’s also a selfish case, Khazan says. Addressing blindspots or imbalances can help us achieve our goals, and feel happier and more fulfilled. At the very least, the attempt can make us more comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Khazan quotes the writer Gretchen Rubin: “‘Accept yourself, but also expect better of yourself’ – I think that’s a good philosophy.”

More from Why am I like this:

Trying to become just a bit more agreeable feels forced at first, just as Khazan warned. But with time and attention, I start to better attune to social interactions. In conversations I try to catch myself before launching into my opinion, to assess whether it was really solicited, and look for opportunities to ask questions instead of making yet another comment.

After two weeks of gentle effort, I realise that when I start being negative for no real reason, I’m probably feeling over-tired, socially awkward or both. It’s strange to notice that I ramp up my views in hopes of generating energy or engaging my conversational partner.

This feels productive: I might not have changed my personality, but I’ve gained more grasp on its expression. If “who we are” is fluid, perhaps I can think of cultivating self-awareness and positive change as growth. Call it 1% more agreeable – or at least less psychopathic.

-

Me, But Better: The Science and Promise of Personality Change by Olga Khazan is out now

.png) 1 day ago

7

1 day ago

7