My first encounter with resistance was unbeknownst to me, and I was annoyed by it. At nine years old, I found myself attending Saturday school, missing Football Focus and not being with my friends playing in the local park. First my sister and I went to the Marcus Garvey Saturday school in Hammersmith. Later we went to the Saturday school in Acton, organised by Mr Carter. He was a light-skinned Black man with slightly ginger hair and freckles, bearing a strange resemblance to Jimmy Carter, who was the president of the United States.

The sole purpose of the Saturday school was to help Black children who were underachieving or being failed by the education system. At that time, I didn’t know that these facilities were organised throughout the United Kingdom by Black parents, teachers and academics. In 1971, a London schoolteacher, Bernard Coard, wrote a pamphlet called How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Subnormal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain. Although there had been efforts to support Black children prior to this, this was the launching pad for a nationwide and organised act of self-determination.

Georgie was an elderly white woman who taught painting and drawing at the Saturday school in Acton. She wore a blue artists’ smock and had short grey hair and glasses. I still remember her knobbly hands and how she held her pencil, drawing horses with fluid lines. I gravitated towards this, and she took a shine to me. I imitated her and fell in love with drawing. She was strict with her gravelly voice but encouraging. Mr Carter, being more academically minded, would put his head around the door to call me for maths lessons, which I hated.

My sister and I were driven there every Saturday in a red Volvo estate by a white guy called Steve who had three daughters, one of whom was Black. There was solidarity and camaraderie, and people helped out wherever they could. This was my first understanding of community and group organisation. The thing about being a Black child and understanding that your environment is not equal is a strange one. You process it in a way that you are always alert, that a part of your brain is constantly aware of the possibility of an attack, micro-aggressions or whatever. You’re not really conscious of it; it’s just part of your makeup, like putting one foot in front of the other.

It’s only now, looking back 45 years later, that I see certain situations in a more conscious light. By constantly campaigning and organising and demonstrating and resisting a system that failed their children, Black parents and teachers helped to eradicate subnormal schools, which undoubtedly I would have attended if this had not occurred. They liberated all children, Black and white, from being tainted with this ugly brush.

My second introduction to resistance was from my neighbour, Milton, who would always post various newspaper cuttings in an envelope with my name on it through our door. These clippings included articles about the miners’ strike and Maurice Bishop, the prime minister of Grenada who had overthrown the previous government in a revolution in 1979. The first time I was introduced to Paul Robeson, the renowned Black American actor, singer and activist, was through a pamphlet from Milton about a memorial service in Wales. I looked at the cover with this Black man’s face and didn’t understand why he was celebrated there. Milton would often ambush me and engage me in conversation across the front garden fence, talking about politics and resistance.

Milton didn’t have children; he lived on his own. I feel part of his job in some ways was to enlighten me to the realities of our surroundings. I would often try to avoid him, knowing that one conversation could take up to an hour. He was an aeronautical engineer and eventually succumbed to asbestos poisoning due to his working environment. But he left his mark. He was the person who helped me ask the questions who?, how?, why? and what? I still have some of these cherished articles, kept in envelopes.

My first demonstration was marching in central London against the introduction of student loans in 1988. I remember the exhilaration of being in the crowd and chanting EDUCATION IS A RIGHT, IS A RIGHT, IS A RIGHT, IS A RIGHT, EDUCATION IS A RIGHT, NOT A PRIVILEGE! I was fortunate enough to grow up at a time when education was free for everyone. I know I could not have gone to art school if I had had to pay to attend. My own resistance started with me loving myself. I had to start by seeing myself as brilliant because no one else did, and to have my ability match my ambitions. This might sound like a tall order, but the only direction for me was down. There were police to arrest me, judges to sentence me and prisons to hold me – that was my reality. My only way out at that time was my ability to draw, which flourished under Georgie’s guidance. It is where I felt myself. It’s where I felt challenged, and it’s where I thought I could strive. My resistance was my courage to dare and push my ability. Through art, my interest in history, geography and literature grew in my later teens in a way that they didn’t at school.

My good fortune was that my family moved to the suburb of Ealing when I was six years old. There I was surrounded by green space to play and imagine. I remember long summer days with my friends in Lammas Park, lying on my back, smelling the fresh grass and looking at the sky. This environment allowed me to dream.

Resistance has been my life, and it continues to be.

-

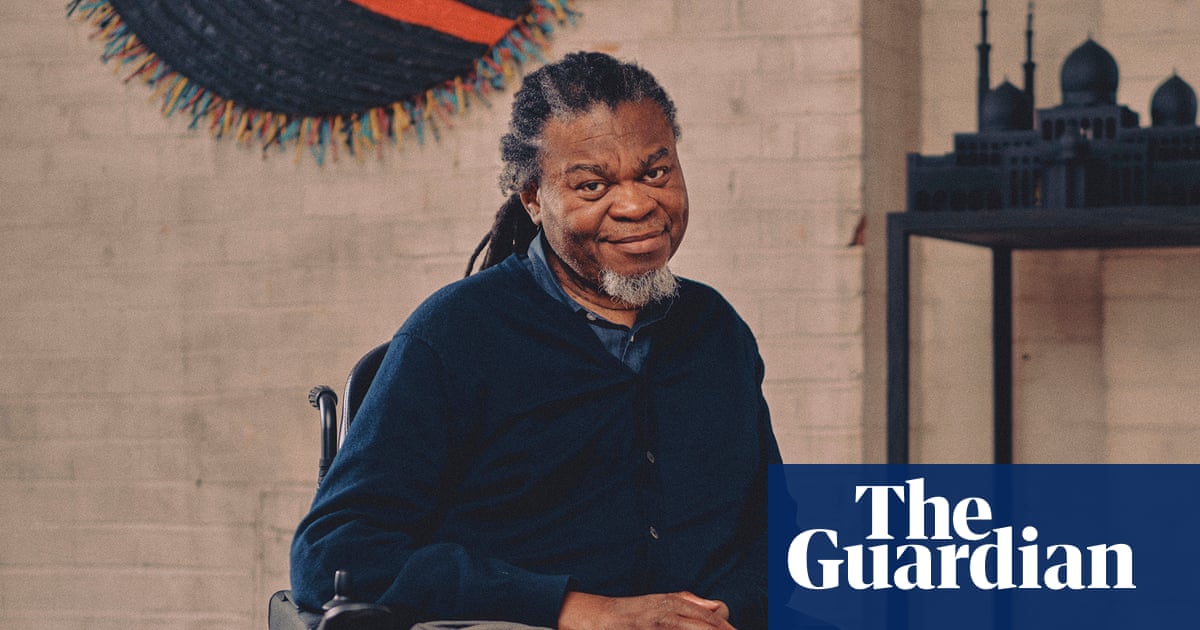

These words and pictures are extracted from Resistance by Steve McQueen and Turner Contemporary, edited by Clarrie Wallis and Sarah Harrison, published by Monument Books on 13 February 2025 (£25). A major exhibition of the same name, curated by Steve McQueen and Clarrie Wallis with Emma Lewis opens at Turner Contemporary in Margate on 22 February 2025. Political research by Sarah Harrison

.png) 2 months ago

37

2 months ago

37