Donald Trump’s decision to impose a 104% tariff on Chinese imports into the US has spooked the financial markets. The response is entirely rational.

Over the past few decades, phoney trade wars have been commonplace. Rival nations have squared off against each other, indulged in a bit of sabre-rattling, but eventually agreed on a deal. Headlines that screamed “trade war looms” were quickly replaced by those that read “trade war averted”.

This time it’s different. The battle between the US and China prompted by Trump’s tariffs is no pretend trade war. It is the real deal – and it will have real consequences. Tariffs operate as a tax, adding to the costs of doing business and raising prices for consumers. Growth will slow and inflation rates will rise. The global economy was already growing only slowly. As things stand, it is now heading for recession.

Trump seems prepared for this, making it clear that he is ready for some short-term pain for what he thinks will be long-term gains: a revitalised US industrial base and higher exports. This also represents a shift in approach. In the past, US policymakers have tended to take fright at big falls on Wall Street and have eased policy to limit the damage.

Not this time, it appears. Or at least not yet. Trump promised to impose swingeing tariffs when he was running for president last year, but the expectation was that this was just campaign rhetoric. Instead, he has delivered on his pledges – and then some.

Despite the obvious parallels, this is not Trump’s Liz Truss moment, where he can be forced into a policy U-turn by a sell-off in US assets. Important though they are, the market turmoil and the heightened risk of recession are only part of the story. Trade will continue despite Trump’s tariffs and China’s tit-for-tat response to them. Talk of the end of globalisation is exaggerated. Rather, the dawn of a new protectionist era represents the end of a particular model of globalisation, an imagined liberal nirvana in which all barriers – to movement of goods, people and money – would be dismantled.

This hyper-liberalised dream world has been on its way out ever since the global financial crisis of 2008, and all that was needed was a final shove, which Trump has just administered. From now on, migration will be restricted, supply chains will be shorter, hands-on industrial strategies will be back in favour, trade barriers will be removed only slowly.

To the extent that this marks a return to the sort of global economy that existed before the hyper-liberals took charge in the late 20th century, this will be no bad thing.

Trump’s tariffs have also raised the temperature in the new cold war between Washington and Beijing. Briefly, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US was unrivalled as a superpower and it was during this period that hyper-liberalism held sway.

Subsequently, China has emerged as a rival to US hegemony and now poses a much bigger threat to continued American dominance than the Soviet Union ever did.

China has gradually been growing in strength since the Deng Xiaoping reforms of the late 1970s, and throughout that period it has been consistently underestimated. It was assumed that China would for ever be a country that specialised in low-cost, high volume goods such as textiles.

That proved wrong, as did the assumption that as China grew richer there would be unstoppable pressure for liberal democracy. For at least a decade, there have been predictions that China’s economy would collapse as a result of a bursting property bubble. That hasn’t happened yet either.

Trump is fully aware that China poses both an economic and geopolitical threat to the US, and appears to see tariffs as the equivalent of the massive increase in military spending by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s that helped bring about the demise of the Soviet Union.

The idea that a 104% tariff will make Xi Jinping blink first represents a huge gamble. China has been busy cultivating new markets for its exports in recent years and is already allowing its currency to slide in order to make its goods more competitive. It has immense financial firepower – and has made it clear that it is prepared to “fight to the end”.

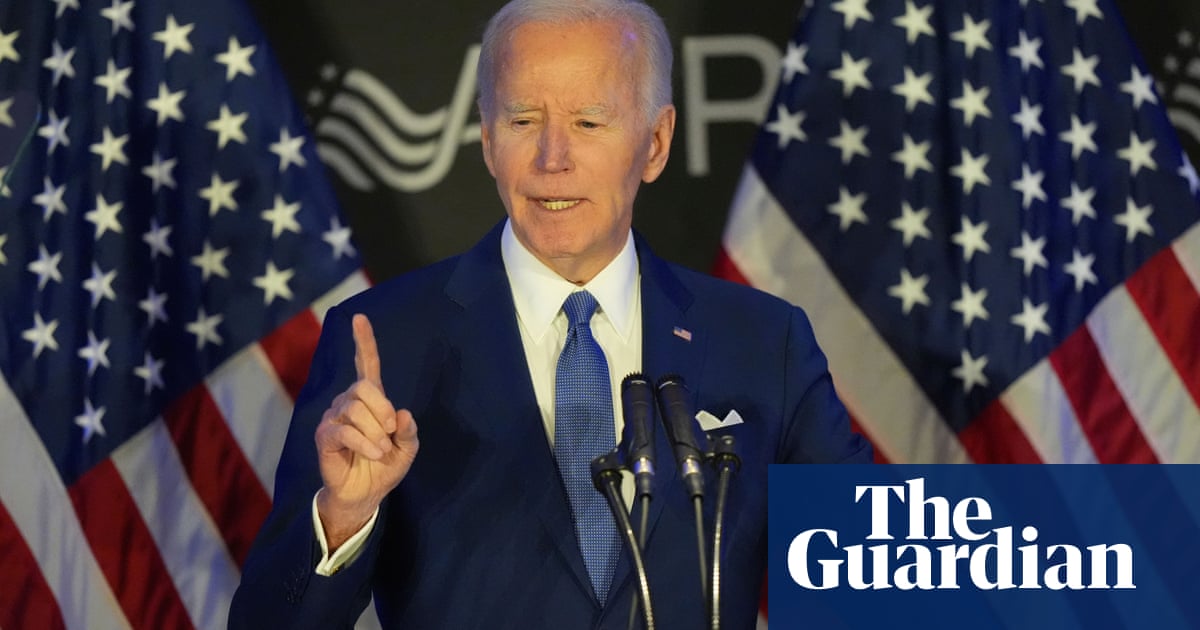

As Joe Biden discovered, the willingness of the American public to tolerate economic pain is limited. Trump’s tariffs are a sign of weakness, not strength, a fear in Washington that the days of US imperial glory are coming to an end. If that is the case, the US is going to need all the friends it can get, which makes Trump’s indiscriminate use of tariffs even more of a risk.

All that said, Trump’s tariffs are a response to a policy vacuum that would once have been filled by parties of the left. The failings of the hyper-liberal model – slow growth, rising inequality, the hollowing out of manufacturing – have been evident since Bruce Springsteen sang his laments to lost rust belt communities in the early 1980s.

The left has proved not just incapable but also unwilling to construct a social democratic response to these failings, preferring instead to fall back on the idea that the global free market was a force of nature that could not – and should not – be interfered with. If rightwing populism is on the march, then that’s because when the call for help came out from communities that felt abandoned, the left was nowhere to be found.

-

Larry Elliott is a Guardian columnist

.png) 6 days ago

9

6 days ago

9