From the road, it’s barely visible; glimpsed, maybe, if peered at with cheeks pressed against the property’s imposing iron gates. There is otherwise little out of the ordinary in this quiet Kent corner of London’s affluent commuter belt – St Michael’s has a village hall, a country club, a farm shop. But at the end of a snaking, hedge-lined driveway is an incongruous home: a sprawling, six-bedroom neo-Georgian mansion, almost every inch, inside and out, covered in the trademark black-on-white line drawings of its owner, Mr Doodle, the 31-year-old artist Sam Cox.

A car honks twice behind me. A woman in her 80s steps out. “It’s mindblowing, isn’t it?” Sam’s grandmother Sue says, eyebrows aloft. “And terribly … different.” The gates ahead buzz open. “Take it slowly,” she offers, by way of warning. “You’ll want to give your eyes a few minutes to adjust.”

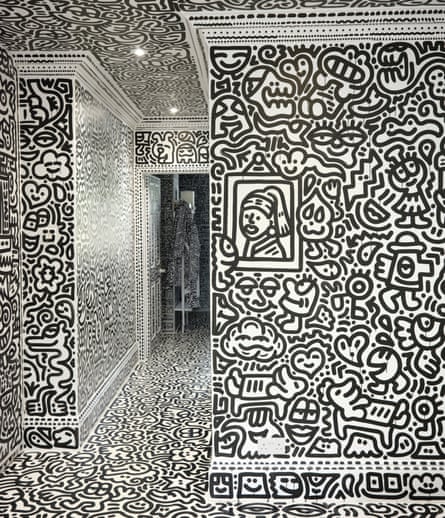

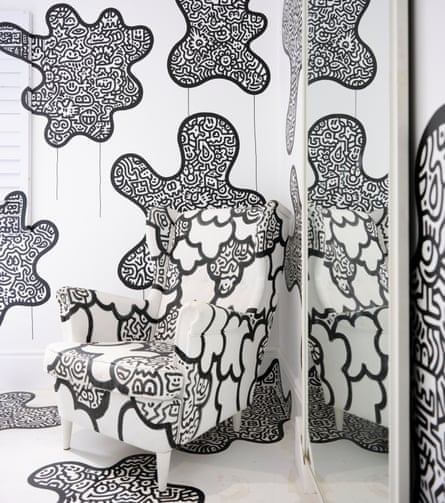

Corner turned, the house comes into unobstructed view: an imposing modern manor enveloped floor to roof in lines, curves and cartoon-ish characters. All exterior walls are doodled over: statues, plant pots, phone box, chimney, guttering and window sashes, too. Standing in the doodled doorway to greet me are Sam and his artist wife Alena, 35, both in full doodle dress-up. “I sometimes say it’s like graffiti spaghetti,” Sam says of his style, inviting me to step over the doodled doormat. “It’s influenced by early-era New York street art, but intertwined, overlapping and cartoonish.” Six-foot-something Sam is gentle and softly spoken – most animated when talking about his work.

He’s joined by younger brother Tom – now Sam’s manager – and mum Andrea. Dad Neill and grandpa David are also on the payroll, today tasked with entertaining Sam and Alena’s two-year-old son Alfie. Having first found success in viral videos during the late 2010s, Sam’s various artistic ventures now earn significant sums: during one nine-month period in 2020, his artwork racked up $4.7m in sales – one piece fetched nearly $1m. That year, he was the world’s fifth most successful artist aged under 40 at auction.

Sam purchased his St Michael’s property for £1.35m in 2019. Its evolution from rural residence to live-in illustrated installation was the realisation of an ambition held for a decade. “I must have been 15 when I first planned it,” he says. “I was set a project called Obsession by my graphics teacher. He wanted me to document my fixation with drawing. I doodled on some furniture, clothes and my childhood bedroom.”

“I was fine with that,” Andrea interjects, as we step into the kitchen: doodled oven, doodled taster, doodled extractor fan. “He also asked to do the family bathroom. That was a no.”

“The obvious next step was a whole house,” Sam says. “It was always a target in my head.”

In December 2019, the purchase complete, Sam’s uncle Graham Wells – a builder – was tasked with stripping the house back to its bones. Every surface, inside and out, was painted white – a nearly 5,000 sq ft blank canvas. It took a little over two years, all in, for Sam to decorate the house in its entirety: spray paint on the outside, black acrylic and bingo markers indoors. The result is a truly transfixing optical overload.

We all settle on the doodled sofas. His parents’ house – where Sam was raised – is a short walk through the village. “I tried to talk him out of it at first,” Andrea says, sipping from her doodled teacup. “We looked around with the last owners who asked if Sam was going to doodle it. No, he told them. I’m not sure it would have been sold to him if they’d known. For the exterior, I came up with all sorts of alternative suggestions. Why not try projections? Then you could switch it off.” Sam was having none of it. “We’ve had no complaints from the neighbours. I know it was your dream,” she glances over at her adult child, “but it was like being in a nightmare at the time.”

Sam, who is listening quietly, fidgets his fingers. To the millions of followers who watched online, the house’s transformation was a triumph. Set to jaunty music, one time-lapse victory video documenting his efforts has been watched some seven million times. What it fails to capture is the devastating toll of the undertaking, now explored in a feature-length documentary due to air on Channel 4. “Midway through the project,” Sam says, “I had a psychotic episode …”

Andrea puts it bluntly: “At one stage, we were worried Sam was going to doodle himself to death.”

The drawing started when Sam was a toddler. “He drew when he was small,” Andrea says, “but, we thought, so do all children. The older he got, the more he doodled. Comics and cartoons first, then video games became his inspiration. By his early teens, drawing was pretty much all he did.” Occasionally, she felt creeping concern .“I’d say, ‘Sam, are you sure you don’t want to go outside for a bit?’ But he was just happy, hurting nobody. Evenings, weekends, any spare time - it was constant.” Socialising seemed of little interest. At night, he could be found doodling under the duvet. “We’d be watching TV, and I’d turn to see him face-down in a page.”

“It was a fun place to disappear into,” Sam explains. “I’d get stacks of A4 printer paper from the supermarket and fill up every page.” All through school, this carried on, encouraged by graphics teacher Morgan Davies, now Mr Doodle Inc’s creative director. “Morgan introduced me to graffiti, and artists like Keith Haring, Yayoi Kusama and Jean Dubuffet.” Aged 15, there was an evolution in his artwork: “What poured on to the page changed from drawings that looked like characters from the Simpsons into what it is today.”

Sam kept it up while studying illustration at the University of the West of England. Friends would often find him doodling in the corners of pubs and clubs. Fuelled by energy drinks, he’d draw for 16 hours a day, sometimes more, as his obsession deepened. “Every day I’d wake up and want to draw,” Sam says. “Anything else was an inconvenience.”

“Must not sleep” became a mantra, scrawled across notebooks – wasted doodle-able hours. During his student days, Sam started to experiment with the idea of an artistic alter ego – a character to accompany his work. He turned up to give a third-year presentation in a fully doodled suit, replete with doodled accessories (fedora, briefcase), announcing he was The Doodle Man from Doodle Land. Friends accepted their quirky mate; others found the vibe … unusual.

The Mr Doodle moniker stuck. Sam began to inhabit this kooky persona with increasing regularity. “I was already handing out Mr Doodle business cards on the street, leaving them on train seats, and throwing them out of my university flat window to try to generate attention. Dressing up and becoming this character felt a natural extension to getting myself out there: a backstory and narrative formed.”

In early YouTube videos, Sam would traverse the streets of Bristol in doodled clothes looking to use his drawings as currency: “I’d try to trade them for stationery, bus rides, a portion of fish and chips. Mr Doodle gave me confidence.”

“It offered him a mask, we thought at the time: a way of being extroverted that didn’t always come naturally,” Andrea says. She wasn’t thrilled by his antics; certainly, she resented being asked to film him bouncing around their garden in a doodle bunny costume. “Only, how could I tell him to stop, when it made him happy?”

After graduating in 2015, Sam set up a studio in his parents’ garage. Commissions started small: office walls, street murals. Then, in 2017, while drawing in an east London pop-up shop, a passerby filmed him at work. That recording ended up going viral on Facebook, and his online influence started to snowball: hundreds of thousands of followers flocked to his accounts. Lucrative brand collaborations followed: Samsung, Disney, Red Bull, Fendi. At auction, his canvases started fetching tens of thousands.

An admirer of Sam’s work, Ukrainian-born Alena – then living in Kyiv – got in touch, and the pair started talking. There were visits to their respective countries, and the relationship got serious.

At the time, Sam oversaw every aspect of his booming business – in part down to his determination to pour every penny into savings, eyes firmly on the doodle-house prize. Sam was stretched beyond his limits: less sleep, more drawing, travelling to Bangkok, Tokyo, Seoul for commissions. He also spent extended periods inhabiting his alter ego, his longest drawing marathon lasting 36-plus hours. That’s when he got the keys to this house. “I thought I would live here as Mr Doodle,” he says, “never seen out of the clothes and character. The boundaries between me and him would blur.”

Work started in February 2020. Those first few weeks Sam felt unwell. “It was physical, initially,” he explains. “Like I had the flu: cloudy head; I was slow to respond in conversation and couldn’t keep up with TV.” A cold, Sam thought. Severe stress, maybe. “I had weird daydreams, hallucinations, panic attacks …”

Once, when Alena was visiting, the pair got an early night. “As Alena was winding down,” Sam says, “I turned to her and said: ‘I’m really worried if I go to sleep I’ll never wake up.’” She tried to calm and console him.

“I’d never seen Sam cry before,” she says, “but I woke up in the night and he was still awake, sitting up, in floods of tears, distraught. Then it escalated quickly.”

Sam was driven to A&E, “convinced he had dementia”, Andrea explains. “He insisted on saying goodbye to us all, certain he wouldn’t survive until morning.” A series of emergency brain scans found nothing. A woman in the waiting room kept catching Andrea’s eye. “This lady was marching around erratically, shouting about the Bible.” It wound up an anxious Andrea. “For God’s sake, I thought, will you just sit down? I was entirely unaware that the next day, that would be my son.” A psychiatrist assessed Sam. His suggestion: take him home and keep an eye on him.

Back at his parents’ house, Sam wouldn’t settle. “There was a look in his eyes,” Alena says. “It wasn’t the Sam I knew in there.”

Sam nods: “The only way I can describe it is that I didn’t know who or where I was.”

His parents reverted to basic instincts. He climbed into their bed and they held him tight, stroked his hair, and encouraged slow, deep breaths. They told him he was loved. “But he wasn’t having any of it.” Andrea shakes her head. “He jumped up and started shouting out the windows and yelling down the stairs. All sorts of nonsense was coming out of his mouth. There was no reasoning with him. So Neill took him back to hospital.”

This time, the psychiatrist was clear: Sam needed to be sectioned. “They were trying to sedate him,” Andrea continues, “but Sam was so manic that the drugs didn’t have an effect. He was convinced his brain was inside the heart monitor, that people were trying to kill him, and that he was no longer Sam. He was running through the corridors shouting: ‘I’m Mr Doodle, and I need help.’ It was as if someone else was inside him, and had taken over his body. Like he was possessed.” He was diagnosed as having a psychotic episode and psychosis.

after newsletter promotion

Sam nods as he listens – his own memories are fuzzy. He knows he was taken to an ambulance. “I was convinced the paramedic was my friend Steve, and kept trying to escape, running around the hospital car park. It was like I’d entered this alternative, Matrix world that I’d invented in my head.”

Eventually, he was corralled into a psychiatric ward in Canterbury, where his psychosis worsened. The next six weeks were a blur: two weeks at one secure unit, then a month at another. “I wasn’t able to understand who or what was in front of me.” He became conspiratorial, believing meals and medication were laced with poison. He was consumed by religious and spiritual delusion. “I believed I was connected to God. That if I breathed deeply, I could control things. If I tapped my right foot, I’d send someone to heaven, or my left foot could send someone to hell. I thought screaming certain words gave me specific powers.” He looks to the family now sitting around him. “And I know I said the worst things to all of them.”

Sam believed he had become the character he’d constructed. On one visit, he turned to Alena and announced, “Sam is dead, call me Mr Doodle now.”

Art was intertwined with his psychosis; at times, it was the only connection the family found to the Sam they knew. “I wanted to draw on the hospital walls,” says Sam, which wasn’t exactly encouraged. “They’d put me in a confined room, and I’d draw on the walls in soup and bread. People coming and going seemed, to me, to be artists I’d been inspired by.” His senses were heightened. “Colours were so intense; if I heard music, it would feel like my whole body was vibrating.” On the psychiatric ward, Sam’s doodling remained relentless. He still has the sketchbooks. “If I drew something square or angular, it was an evil character. Circular, bouncy shapes were happy and angelic. There are lots of notes about God and religion scattered through.

It was like I was living in Doodle Land, and I didn’t know how to get back again.”

When doctors discharged Sam in April 2020, he was still unwell. At home, he’d sit, having imagined conversations with Donald Trump and Kanye West. One time, midway through a chat with his mother, Sam declared: “You’re not my mum, you’re Nigel Farage.” It didn’t help that the pandemic was in its early stages. “I was already distrusting of things – then there was talk of this disease. I was convinced it was a plot.”

“We could be anywhere,” Andrea expands, “and something would switch: he’d see something not there, or believe something entirely irrational. We’d be quietly watching TV, and Sam would turn around and ask: ‘Why are they talking about me?’ It could take hours to talk him down. We couldn’t even watch David Attenborough – Sam thought the rocks were giving him dirty looks.”

Occasionally, flickers of the old Sam returned – initially, in conversation with his grandparents. Over months, these became more regular. He only came off the last of the medication in early 2024.

Psychotic episodes can be triggered by substance abuse, sleep deprivation, stress or specific physical conditions. “I didn’t feel stressed at the time,” Sam says. The family doesn’t seem convinced. “But there was definitely too much in my head.” Episodes such as this have no clear end point, and doctors couldn’t guarantee it wouldn’t strike again. Sam was unperturbed and, within weeks, wanted to return to project Doodle House. “I thought you should never draw, never be Mr Doodle again,” Tom says. “That this place would have to be abandoned.”

“I tried to talk him out of it,” Andrea says. “But he was determined. So we just encouraged him to take it slow, not all day and all night: stop, walk, break, breathe. Alena was here, keeping Sam under control, making sure he took breaks and his tablets.”

The pandemic helped, slowing Sam’s other projects. His parents took over the business admin. “Plus, I was sleeping a lot more because of the medication,” he says. “There was no 24 hours of nonstop drawing, as before.” Joey the cockapoo’s arrival was a boon. “I’d stop drawing to take him out for walks.” Soon, Alena was pregnant – another responsibility.

The documentary, the family hope, marks an end to this chapter. “Speaking about it has made the whole thing feel more normal for all of us,” Andrea explains. “Before this, I’d never been inside a psychiatric hospital.” The topic feels taboo, perhaps, even in an era of mental health awareness. “When Sam first got ill, I wasn’t telling people – not embarrassed, but I didn’t understand, or know how to explain. Now we just talk about it as if he had appendicitis.”

Sam and Alena take me on a tour, past doodled walls, floors and ceilings; lamps, log burner and chandelier; dressing gown and laptop; toilet and bathtub. There’s a doodle garage, complete with doodled Tesla. Dream-themed doodles decorate the bedroom; each of the 2,000 tiles in its en suite bathroom are adorned with appropriately aquatic doodle designs. We step outside, passing the doodle water butt and American yellow school bus, through the evolving sculpture park.

In the back corner of the four-acre estate is an imposing, newly constructed modern studio, designed by architect Guy Hollaway. Its exterior is wrapped in metal panels, each with intricate laser-cut doodle shapes. Inside, white double-height walls provide Sam with a blank backdrop to work on. In one corner, floor-to-ceiling racks display his recent works. The smallest among them sells for roughly $80,000. Another corner displays a grid of square drawings, each with crisscross coloured lines. It’s a new style he’s experimenting with, inspired by the NHS-issue felt-tip pens he relied on while hospitalised.

The studio is a flurry of activity: Tom is taking a phone call, Alena moves materials around. Photographs are being taken. In the corner, at a table, Sam sits, thick, black pen in hand, entirely at ease. Smooth, freeform lines fill up the white page. Swoop, circle, dot dot dot. Up to the corner, looping down. Squiggle, glide, squiggle.

Alena perches next to me. “The first time we met,” she tells me, “Sam told me this was his dream: to buy the big house, and to doodle it. I knew what I was signing up for.” I’m not convinced that grandma Sue was right, I say: my eyes haven’t yet adjusted. “When we first started,” Alena replies, “I couldn’t imagine living there. It was so sterile. But I started to make it homely, with little softening details. Now it’s home. It’s not too much for me, honestly, any of this. Without doodles, Sam and I would never have met. I find them comforting.”

“When I start drawing,” Sam says, “I don’t think before shapes and characters just merge into something. I enjoy the physical feeling of moving the pen along the paper – it’s like that sensation of spreading soft butter on toast. It just feels satisfying. The noise that it makes. I feel content in myself when I do it, emotionally. It’s when I’m happiest. Seeing the work made in front of me is a high – it’s that feeling I’m chasing each time I draw. This itch that’s satisfied by seeing work appearing in front of me.” He still feels that intense pull to draw: “I don’t get lost in it now, but left to my own devices, I could do this for ever”

.png) 2 months ago

31

2 months ago

31