Three days before Hamas’s 7 October 2023 attack on Israel, I was helping friends who live in Gaza City gather armfuls of guava in their orchard in Beit Hanoun, in the north of the Strip, when something strange happened.

Hamid and Rania* had bought the small plot the year before. It was overgrown, but over the changing seasons they’d worked hard on their expensive acquisition. I called it the secret garden, a tiny oasis in the midst of the dry, dirty misery of Gaza.

As well as guava, there were apple, fig, lemon, orange and olive trees. The couple planted grapefruit and pomegranate saplings, and dug vegetable beds for tomatoes, herbs and spices. Rania also put in yellow and red chrysanthemums in flowerpots made out of stacks of worn-out car tyres.

The couple bought a water tank and fixed the broken outhouse. The existing shack, originally little more than breeze-blocks, a dirt floor and tin roof, was refurbished, complete with a bed and a shady roof terrace.

From the terrace, you could see the Mediterranean sparkling in the distance. To the north, usually only half visible through the mist, were the towers of a desalination plant in the Israeli city of Ashkelon. The plot was surrounded by Gaza’s biggest area of open, flat agricultural land, which mostly amounted to a few other small walled orchards and strawberry fields. Teenage boys often herded scraggly goats and sheep through the area.

It had been a day like any other until the sound of men’s voices, shouting in unison, carried to us over the wind. It sounded like a military drill.

We went up to the roof terrace, from where we could see several dozen men, standing in formation, in a fallow field. Even from a distance it was clear they were wearing the bright green insignia of Hamas’s armed wing, the Qassam Brigades.

None of us had ever seen so many fighters in Gaza out in the open before, let alone training in full view of the farmers around them and Israeli drones above. Outside wartime, that uniform was usually reserved for funerals and rallies. Along with the rest of the world, we found out the purpose of the drill soon enough.

I left for Jerusalem the next morning, through the border fortress the Israelis called Erez, and went to Shabbat dinner with Jewish and Arab Israeli friends that night. How was Gaza, they asked, always curious about a place they could never visit. Quiet, I said. So quiet, in fact, I’d been able to interview people for a feature about the revival of beekeeping there. I thought the fact that the bees could travel further than their Palestinian owners, flying over Israel’s border fence to greener pastures, would make a good story.

But, of course, I never wrote that article. Instead, I was soon on the other side of the barrier from Beit Hanoun, running from incoming rockets, getting caught in crossfire between Hamas and the Israeli army still fighting in a kibbutz, and retching at the smell of the bodies of murdered families decomposing in the unseasonal heat.

I took the job as the Guardian’s Jerusalem correspondent in 2021, although I was reluctant about it. I was happy living in Istanbul as the paper’s Turkey and Middle East correspondent, from where I got to travel widely – and the Jerusalem gig was notoriously thankless. Every single word published under my name would be forensically examined for signs of bias. Plus, I found the holy city difficult – tense and unfriendly. Jerusalem is a place that attracts fanatics and zealots; one American man with Jerusalem syndrome was always wandering the streets of the Old City, barefoot, staff in hand, convinced he was Moses. I had visited several times before, but what did it say about me, I wondered, that I was willing to move here, and take on this challenge?

My partner was encouraging, even though we knew holding an Iraqi passport would make it difficult for him to join me. Any outsider or journalist who wants to truly understand the Middle East should spend some time in Israel and Palestine, he said.

In the end, I took the job – and now, four years later, I am leaving Jerusalem and returning home to take up a post in the UK. I have learned a lot, and the experience has changed me.

Before I arrived in Jerusalem, I thought the Israel-Palestine story was an old one: a cycle of attritional violence and a slow march towards inevitable annexation because of Israeli settlement building in the West Bank.

The Abraham accords, diplomatic agreements brokered in 2020 in which several Arab nations agreed to recognise Israel, seemed to suggest that the rest of the Middle East had lost interest in the question of Palestine. The conflict had also been pushed down the global agenda by the regional wars and crises triggered by the Arab spring, the war in Ukraine and China’s increasing power. Even so, during my time there, it was becoming more likely that something big was going to happen.

Many years ago I interviewed a pilot who explained that plane crashes don’t happen without warning signs first: system A fails, or is faulty, and then B, and then C, and then D. It’s always a series of events, rather than a one-off incident, that leads to a plane falling out of the sky. Israel and Palestine before October 2023 felt like that – like the dominoes were being lined up.

Before 7 October, 2023 had been a difficult year. In December 2022, Israel’s pugnacious prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, had returned to office as the head of a new coalition that was the most far right in Israeli history.

It proposed an overhaul of the judiciary that would essentially give the government full control over the courts, which critics said undermined democracy. In early 2023, there were mass protests in the streets and by July military reservists were refusing to report for duty. Israel’s enemies and friends alike warned the government it made the country appear weak.

Meanwhile, in the West Bank, 2023 had already beaten 2022’s record as the bloodiest year since the close of the second intifada, or Palestinian uprising, of the 2000s, and I spent much of the year driving back and forth to cover massive Israel Defense Forces raids in Jenin and Nablus.

It’s strange to say this now, but in comparison with Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and the West Bank, Gaza had been relatively quiet. After the last major war in 2021, Israel had gradually increased permits for men from the Strip to enter for agricultural and construction work, an incentive for Hamas to keep quiet by doing something to alleviate the besieged territory’s dire poverty and accompanying social unrest.

The money was making a huge difference. Every time I visited the Strip, new shops and cafes were opening, and the rebuilding from the last war had almost finished. Friends, sources and people I interviewed told me that the cash had helped them clear debts from failed investments and business ventures – a common story in a place where the economy could not function normally.

There is now a tendency to wax lyrical about how wonderful Gaza was before 7 October, but life there was still very hard. One elderly friend of a friend went blind because Israel did not consider cataract surgery a valid reason to be allowed to seek medical treatment abroad, even though the treatment was not available in the Strip. Another woman I interviewed needed chemotherapy for a recurrence of breast cancer, but nine travel permit applications were refused. Permission only came through after I wrote a story about her.

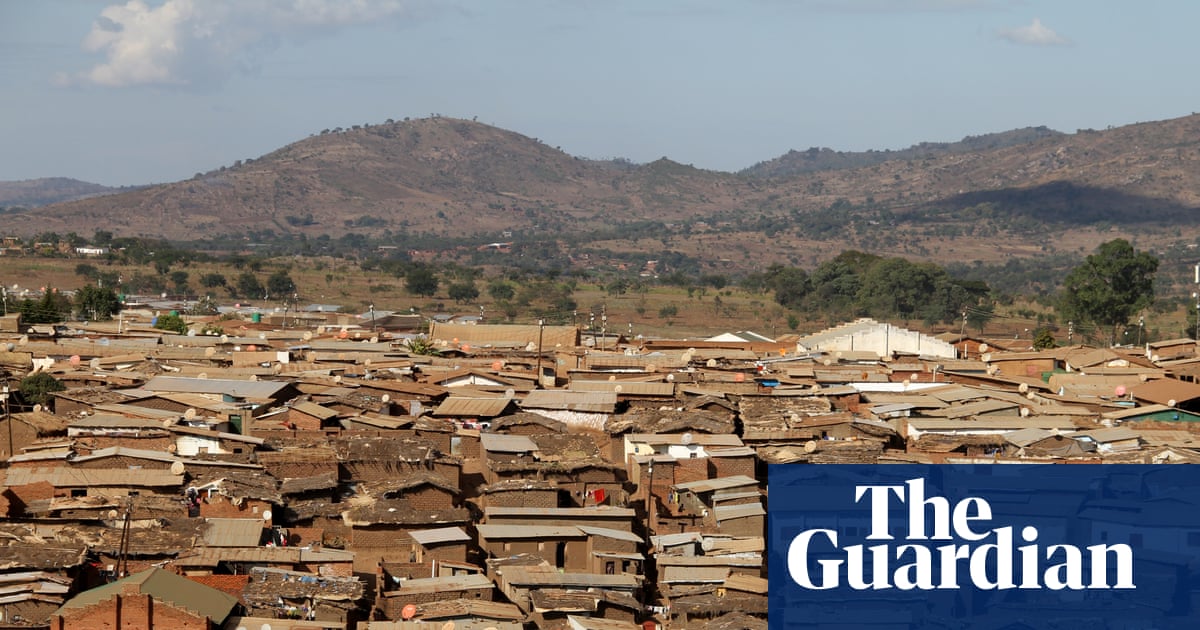

I never felt that I properly understood the reality of the Strip until I visited it. None of the reporting I’d read or watched could adequately convey the claustrophobia, the busyness, the dirt, the suffocation, the feeling of being trapped. It was a struggle in my own output, too. There is – or was – nowhere else like it.

The Strip was the first place I went to when I started the job – and from there, I went straight to Tel Aviv. I remember sitting on the beach in nearby Jaffa early that morning and feeling a maddening cognitive dissonance. How could people be out and about, doing pilates, walking their dogs, as if everything was fine – when just 50km down the road, on the same stretch of the Med, was an open-air prison? I was worried that I too would start finding the situation normal. But it never happened.

Another time, I stopped off at an Ikea on my way home from Gaza, a mistake I didn’t make again. My brain couldn’t handle the switch between the slum-like Shati refugee camp and a world of well-lit, flat-packed plenty in the space of a few hours. I had to go outside to get some air.

Still, everyone clings to their memories of the before times: Gaza’s spicy food and fresh fish, the bountiful orchards, clambering around Ottoman ruins, late night nargileh (hookah) sessions – and most of all, the beach. In the summer of 2022, Israel allowed more electricity to reliably reach Gaza’s sewage treatment plants, and for the first time in years, most of the Strip’s coastline became clean enough for swimming. On the busy beaches, children ran in and out of the waves, begging their parents for camel rides and candy floss.

It was a glimpse of what a different Gaza and a different future could look like. Now, all of that is gone, replaced by an apocalyptic moonscape so unrecognisable that friends tell me they get lost in their own neighbourhoods. A long time ago, I ran out of things to say in messages and voice notes to the people I know there. My pleas for them to stay safe became meaningless. Instead, we don’t talk about what they are going through, mostly reminiscing about old times, or we make plans for the future. No one acknowledges that we can’t be sure they will materialise.

If I think about the first few weeks of the war now, what surfaces first is the prickly, uncomfortable memory of the heat. The semi-desert western Negev, which makes up Gaza and southern Israel, is totally different from high-altitude Jerusalem, and for much of the year the landscape is so barren and harsh it feels as if the sunlight bounces off it with a vengance.

It was such a warm autumn, far too hot: still over 30C at the end of October. Then comes the feeling of chaos, the fear and panic, rather than specific incidents – the Guardian’s hotel in Ashkelon getting hit by a rocket, or stumbling across the headless corpse of a Hamas fighter. (To this day I still don’t understand where it could possibly have gone; he was otherwise in one piece, and so were the bodies around him.)

I told my family and editors, all far away in the UK, that I was OK – which, to an extent, I was. I was still in shock, so I focused on the work and adrenaline carried me through. I was far more affected by the stories that traumatised 7 October survivors told me – and about what was going to happen to Gaza – than by what I saw first-hand. Nothing was clear at that point except that many, many more people were going to die.

The dam broke about three weeks in, when I went to report on the funerals of a British-Israeli family: mum Lianne, and teenage daughters Noiya and Yahel. Their father, Eli, was taken hostage. He didn’t find out his wife and children had been killed until he was released during the ceasefire earlier this year.

Watching the grief of those gathered to mourn loved ones taken away by such senseless and shocking violence, I began sobbing uncontrollably and had to leave the graveside to sit in a corner of the cemetery where I wouldn’t disturb the eulogies. A member of the family came over to ask if I was all right, and whether I had known them; I didn’t know how to explain what I was feeling. I just cried on her shoulder instead.

I am leaving the Holy Land at a strange juncture. I never planned on staying much longer than three years, and I never signed up to cover a war like this. Unlike my Israeli and Palestinian friends and colleagues, I have the freedom and ability to leave.

Fundamentally, I feel the same as when I arrived – that the occupation is wrong, and it doesn’t make Israelis safer. For decades, Israel told itself a lie that the conflict could be contained and managed, sustaining a perpetual occupation and suppression of Palestinian rights without any major diplomatic, financial or security cost.

That myth was shattered in the early morning of 7 October 2023. I understood what was at first a blinding Israeli need for revenge, even if I didn’t agree with it, and I knew that they needed to make sure nothing like that bloody day could ever happen again. But since then, the last hope anyone I know had for a diplomatic solution to the conflict has been extinguished. Israel has doubled down on force. The slow suffocation of Palestinian hopes of dignity and statehood that was unfolding when I arrived has accelerated at a pace no one could previously have imagined.

When I started out in journalism, as an assistant at the London offices of the Associated Press, I’d spend all day fielding phone calls, copy and video files from our correspondents around the globe; I used to note down their locations and loglines enviously, eager to get out and see the world for myself. I used to think journalism could help right wrongs, and I could play a role in that, but covering the wars in Syria, Yemen, Iraq and now Gaza over the past decade has taught me that is not necessarily the case. My coverage didn’t do anything to stop those horrors unfolding, but at least it showed the rest of the world the reality on the ground.

Martha Gellhorn, one of the greatest conflict reporters of the 20th century, wrote about feeling like a “war tourist” in her work. In Gaza – where Israel has blocked access for international journalists – I haven’t even been that. Thanks to the sacrifices of my brave colleagues in Gaza, no one with an internet connection can say they don’t know the truth of what has happened in Israel and Palestine over the past 18 months.

There is no silver lining here, only lessons we may not fully understand for years to come.

The late Pope Francis, who called the congregation at Gaza’s sole Catholic church every night until the day before he died, used to comfort his flock by reminding them that all wars end. I remember a Gaza where hope of a better future was still alive. As soon as it is possible, I will return to the Strip to sift through the rubble of ruined lives and help reclaim what has been lost.

* Names have been changed

.png) 3 months ago

63

3 months ago

63