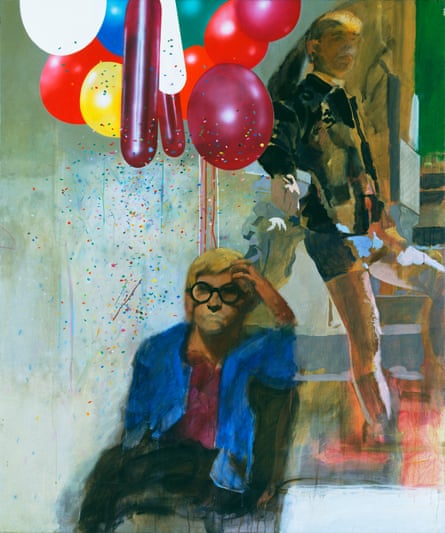

When Peter Blake painted a portrait of his friend David Hockney in 1965, he based it on a photograph. Why? He got on with his fellow Royal College of Art graduate and could have got him to pose. In fact, their relationship was relaxed enough for Hockney to suggest Blake include the male youth in Austrian jacket and shorts who stands behind him – also taken from a photograph.

Hockney, with his round spectacles and bleached hair, looks right at us – or rather at a camera. Blake tries to capture in paint the photo’s harsh light and shadows, contrasting the secondhand, reproduced, even two-dimensional figures of Hockney and the youth with a bunch of balloons that are given a shiny, robust three-dimensional force. By painting a photo of the artist, instead of the artist, Blake suggests distance, mystery, loss. Hockney has become a kind of pop star and doesn’t seem quite real any more. The Bradford-born painting sensation had recently moved to Los Angeles, and it looks like the British-bound Blake is missing him.

To be an icon is to be remote from others and maybe from yourself. Icons of the 1960s float by like lonely astronauts in the Holburne Museum’s fascinating rethink of pop art. Yuri Gagarin, the first person in space, is among them in Joe Tilson’s Gagarin, Star, Triangle, his face screenprinted from a photograph and enlarged so we can see his smile. But Tilson is marking Gagarin’s death in 1968. Ursula Andress gloriously emerging from the sea in the Bond film Dr No is collaged with a nuclear fallout shelter sign by Colin Self. And in Richard Hamilton’s pink and red screenprint My Marilyn, we contemplate a sequence of publicity shots of Marilyn Monroe, most of which have been crossed out by the star herself. Irradiated by Hamilton’s printing process, Monroe’s images, chosen and rejected, look spectral and unreal. She is simultaneously here and gone, found and lost.

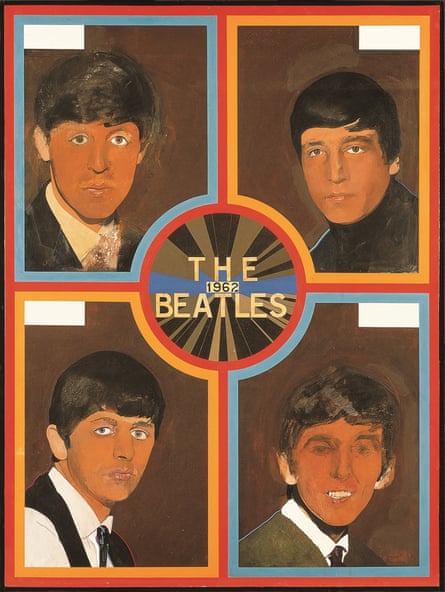

Artists have been fascinated by photography since the invention of the camera, but in the 1960s the combination of photos, film and mass reproduction spawned the media age. The real story of pop art, this compact but brilliant show suggests, is how painters responded to the secondhand nature of experience, the replacement of real life by mechanical images. It is an unexpectedly introspective look at a time often caricatured as the plastic fantastic age. In another slyly meditative masterpiece by Blake, we look up close at the faces of the four Beatles in 1962, enlarged from a publicity image. When Blake finished this painting in 1968, its image of the Beatles, suited and mop-topped, was already out of date, nostalgic.

While some icons of the 60s still walk as gods among us – Mick Jagger, too, is here in Hamilton’s masterpiece Swingeing London – others are touchingly of their time. Gerald Laing puts a target-like circle round the face of Brigitte Bardot, whose features he renders in black dots to replicate the look of old newspaper photos. Pauline Boty takes you back to a cinephile decade in her portrait of Jean-Paul Belmondo, grinning and sporting shades, as if he has just stepped out of his cocky performance in Godard’s À Bout de Souffle. She renders him in black and white as in that film, but from his straw-hatted head sprouts a huge, gorgeously painted crimson flower. And lest you miss that she is a fan, there are hearts along the top of the painting.

Iconic is subtitled Portraiture from Francis Bacon to Andy Warhol, but Bacon is an outlier. It is true he used photographs but he is scarcely aware of celebrity, unless you count Pope Pius XII, who stars in one of his paintings here. However, the show ranges decades earlier to include a painting by Walter Sickert. By the 1930s this uneasy artist, born in 1860, was a lingering ghost from another age – or so he depicts himself in his slightly creepy 1935 self-portrait. He has seen himself in a newspaper, photographed in the street, an old relic in a baggy check suit and bowler hat. His painting reproduces this black-and-white photo to make you share his sense of shock. Sickert sees himself as others see him, as the cold cruel camera sees him, as a shambling old fool. He finds in the media glare nothing but self-alienation and a foretaste of death.

There is true terror, too, in Warhol’s 1967 Self-Portrait, which looks enormous in this little gallery. As you approach it, his features come apart in clouds of blue and red. Based on a photograph in which he poses thoughtfully, with his fingers cradling his chin, this magnificently loose and juicy painting loses sight of the silkscreened image as Warhol and his Factory assistants roll and splash on paint in abstract abandon. His face becomes a kaleidoscopic negative image, his eye vanishing in a red explosion, an entire side of his face turned to pink mist. He is all colour, all light, all fame. He sees himself disappear.

Like the media age itself, this exhibition shows pop art beginning with innocent fun and turning into nightmare.

.png) 3 months ago

46

3 months ago

46