Talking about fire and Los Angeles is an exercise in repetition. Southern California does have seasons, Joan Didion once noted in Blue Nights, among them “the season when the fire comes”.

Fire in Los Angeles has a singular ability to shock, with its destruction that takes “grimly familiar pathways” down the canyons and into the subdivisions. The phrase comes from Mike Davis’s 1995 essay The Case for Letting Malibu Burn, and it is as true for the fires as for our talk of the fires. Even our reflections take on that grim familiarity: we cite Joan Didion citing Nathanael West. We fall in with the great writers of this great city who are always so ready to judge it.

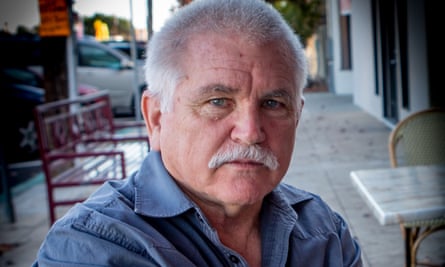

LA’s fires are usually interpreted as a verdict on LA. Eve Babitz tells the story of the silent film star Alla Nazimova, who had to save her possessions from a fire and decided to rescue none of them: “It’s a morality tale,” Babitz says, “of the unimportance of material things, though there are those who will say it’s about how awful LA is.” The writer and activist Mike Davis was different: in books like City of Quartz, Ecology of Fear and Dead Cities: And Other Tales, he defended the city and its people, reserving his indictments for the forces of untrammeled capitalism and white supremacy that had molded it into near-uninhabitability. He read the city as a sign of what was to come, leery of a world that had assigned this complex, maddening, beguiling place “the double role of utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism”.

Davis wrote The Case for Letting Malibu Burn under the impression of the conflagrations of the late fall of 1993 – including one in Topanga Canyon that dived down the hillsides towards Malibu, and one in Eaton Canyon that ripped through Altadena. Two places, that is, that are aflame this week again.

And yet, without much changing, much has changed.

When the flames this week returned to Topanga Canyon and Eaton Canyon, when they spilled out into Malibu and Altadena, they did so on a previously unimaginable scale. Five thousand structures have burned in each place – expansive hillside mansions, ordinary tract homes and apartment buildings. At least 11 people are dead as of the time of this writing, and the fires are barely contained. Climate change is transforming California, and it is changing how California, a place so used to catastrophic burning, burns. When Davis was writing, exactly one of the 20 most destructive fires in California history had taken place. In Didion’s case, three. That’s before this week’s fires even enter the record books, as they surely will.

In looking back at their accounts, some of the cool with which they assess the fires has to do with the kind of regularity that can be found at the beginning of an exponential curve. But reading them today, in the midst of catastrophic climate change, you get a sense for how what was nearly normalized gradually escalated to become unprecedented. Southern California’s fires were the catastrophes one learned to live with, until they weren’t. Davis in particular was unusually perspicacious when it came to the foreshocks of this development.

Davis’s essay told the story of a natural landscape prone to periodic but minor burns forcibly overlaid with a secondary geography: one shaped by large lots, lavish private homes, well-funded firefighters, generous insurance rates, and endless cars, resulting in far more rare but absolutely cataclysmic fire events. An artificial “ecotone of chaparral and suburb” that “magnified the natural fire danger”. What resulted, Davis observes, was a government doing less and less to help the most needy living in the area as it bought itself, at the pleading of homeowners worried about their property, police helicopters and wide-bodied planes to gobble up ocean water to release over burning hillside homes.

Like Los Angeles’ pleasures, its agonies are collective but privatized. Davis was their great chronicler. The fire-prone areas of Malibu, he noted, might have been a publicly owned and managed park, had Frederick Olmsted Jr had his way. The architect had proposed turning much of the Santa Monica Mountains into public land. Instead the area remained privatized and isolationist, a playground for developers and homeowners’ associations. And each new house built higher into the hills further socialized the risks and privatized the area’s gorgeous benefits. The one morsel tossed to the broader public – typical for the region – was the Pacific Coast Highway, which “gave Angelenos their first view of the magnificent Malibu coast”. As Davis noted, it also “introduced a potent new fire-fuse – the automobile – into the landscape”.

The Case for Letting Malibu Burn draws its power from the fact that fires are never singular in the LA area. They pop up in various locations, fanned by months of dryness and the pervasive Santa Ana winds, and braid together the region, rich and poor, mobile home and hillside villa, inland community and the coast. Wherever they pop up, they strike at the area’s characteristic building type – the standalone single-family home. In City of Quartz, Davis chronicled the rise and the often outraged defense of this type of dwelling against “suburban deruralization”.

The fires are great levelers, but they are also great dividers. The same week in 1993 during which Topanga and Eaton Canyons burned, so did a large and overcrowded tenement in Westlake, killing 10. This is why his essay pairs Malibu – “the wildfire capital of North America and, possibly, the world”, as Davis remarks – with Westlake, which led the rest of America in “urban fire incidence”. In an essay called Dead Cities: A Natural History, Davis pointed to the role that arson played in remaking many of the urban centers further east. But LA didn’t need arsonists. It had lax fire codes, homeowners’ associations constitutively hostile to apartments and apartment dwellers – and the Santa Ana winds.

Davis contrasts Malibu’s constant ability to be surprised by the regular avalanches of fire pouring down Topanga canyon with the shrugs that greeted the often far more deadly tenement fires. Where Los Angeles allocates resources, whose lives it values – all that is, for Davis, all the more starkly illuminated by the wildfire flames. This week, nearly 800 incarcerated firefighters battle the deadly flames for a daily rate ranging from $5.80 to $10.24 (plus $1 for active emergencies, apparently). All this while billionaires use social media to angrily demand why their water is running out and where their tax dollars have been going. Private firefighters have been protecting their clients’ houses using public hydrants. Other services are sent out by the large insurance companies.

Davis pointed to these developments decades ago. Perhaps that is the most horrific takeaway from this week’s fire: that these traumas are seasonal as before, only much worse. This is the sense of regularity in the midst of the apocalypse that runs through much of Davis’s writings on LA. And through is that most awful sense of all: that none of it was necessary, that it could have been different. In this respect we all are, or are on our way towards, becoming Angelenos.

“Los Angeles weather,” Didion writes in her essay about the Santa Anas, “is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse.” If you read it in Didion’s patrician, detached cool, it sounds almost coy. The weather is apocalyptic, but in the end the apocalypse is just weather. In the age of accelerating climate change, we no longer can afford that detachment. Because of course it is no longer just Malibu that is burning. It is no longer just the fire season that we fear.

In October 1942, the writer Thomas Mann complained about the “stifling heat” in his diary. From the garden outside his Pacific Palisades home he read news about the faraway war, and he noted “a destructive fire in the canyons nearby”. Two catastrophes to which a man standing on his lawn in Pacific Palisades was safely a spectator. This week, the Palisades fire carried the flames almost all the way to Mann’s garden. What do you do with a region that has long fixated on the apocalypticism that slumbers in its everyday, at a moment when the apocalypse becomes normalized the world over?

.png) 3 months ago

38

3 months ago

38