At a conference held at London’s Somerset House as part of the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in 2015, the name of the organiser came up again and again. “Koyo Kouoh” hooted an Iranian participant to her eager audience. “We need to have her cloned.”

Over the decade that followed, it seemed as thought this might actually have happened. Kouoh, who has died aged 57 after being diagnosed with cancer, was impossibly ubiquitous. In 2015, she was living and working in Dakar, Senegal, where in 2008 she had set up an artists’ residency called Raw Material. Seven years later, Raw Material had come to include a gallery, exhibition space and a mentoring programme for young Senegalese artists.

Four years after that, in 2019, Kouoh was made director of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art (MOCAA) in Cape Town, South Africa – the largest institution of its kind in the world, but at the time on the point of closing down. “I was convinced that the failure of Zeitz would have been the failure of all of us African art professionals,” Kouoh recalled in a podcast in 2024. “For me, it became a duty to save it.”

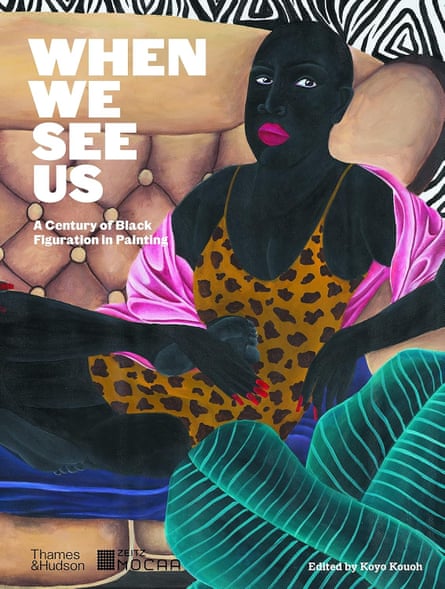

Among other groundbreaking exhibitions curated by Kouoh during her tenure at Zeitz MOCAA was When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, in 2022. This was still running at the time of her death, having moved to Brussels’ Bozar centre earlier this year. (It closes on 10 August.)

The New York Times praised the “sophisticated breadth … aesthetic and art historical, painterly and political” of the show, and the curatorial thinking behind it – in particular, its exploration of what Kouoh called Black self-representation from across Africa and the Afro-diaspora.

Kouoh described herself as a pan-Africanist, embracing the term “Black geographies” to include all those parts of the world in which Africans had, for the most part involuntarily, found themselves. “Their cultures have evolved, transformed and taken root,” she said. “Their territories become extensions of the continent. So, from my point of view, Brazil is an African country, Cuba is an African country, even the United States.”

As well as her formal posts, Zeitz’s director had twice been on the curating board of Documenta in Kassel, Germany, organised Ireland’s EVA International biennial in 2016 and a keynote exhibition at the Carnegie International in Philadelphia in 2018.

At the end of 2024, Kouoh was named as commissioner for the 61st Venice Biennale, only the second African to be chosen for the job, and the first African woman. She died the week before she was due to announce the biennale’s programme and theme.

There was little in her past to suggest a stellar career in the international arts. Born in Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon, Kouoh described her background as “very modest”. Her great-grandmother had been forced into a polygamous marriage as a teenager; her grandmother was a seamstress; her mother, Agnes, left Cameroon in the 1970s to look for work in Switzerland. “This is the family I come from,” Kouoh told ARTnews. “That is the essence of my feminism.”

At 13, Kouoh joined her mother in Zurich. Like many children of aspirational immigrant parents, she was nudged towards a career in finance, studying economics and becoming an investment baker at Credit Suisse. Her heart was not in it.

As she told the New York Times in 2023, she was “fundamentally uninterested in profit”. It was while working in Zurich that she met a pair of Swiss-German artists, Dominique Rust and Clarissa Herbst. The world they introduced her to was captivating. In October 1995, Kouoh left for Senegal as cultural correspondent for a Swiss magazine.

There were other reasons for her departure. Shortly before, she had given birth to a son, Djibril. True to her matriarchal roots, she would bring him up by herself: “I couldn’t imagine raising a Black boy in Europe,” she said.

The discovery, in Senegal, of her own, non-European identity had come as a surprise to the young, Swiss-educated banker. “I realised I was African and Black,” she told Le Monde in 2015. “It was then that I first felt a hunger for Africa.”

Her early studies in economics helped clarify her later thinking. “Money is a fundamental component of our existence,” she said. “Every sphere has its own economy, and art is no exception.” In this, too, she saw an African exceptionalism. The western model has been to measure artistic success by success in the saleroom.

“In Africa, it’s a completely different story,” Kouoh said. “I’m happy for artists who are successful in the market, but that is not synonymous with worth.” Her own philosophy, central to her curating and directing, was collaborative rather than competitive.

One of the more surprising things about her appointment as commissioner for the Venice Biennale was that it was made by Pietrangelo Buttafuoco, the one-time leader of the youth wing of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement party and an ally of Italy’s far-right prime minister, Giorgia Meloni.

What form Kouoh’s biennale might have taken – indeed, whether the biennale will now take place – remains for the moment unknown. “I will, of course, be bringing my intellectual and aesthetic baggage to Venice,” she said recently, in an interview on the website Next Is Africa. “It will be true to my obsessions and my values.” Punning in French – one of a number of languages she spoke fluently – she laughingly said: “Venice has given me carte blanche, and I am going to play my carte noire (black card).”

Educated by Jesuits as a child in Douala, she came to embrace broader beliefs. After a merry interview in the Financial Times earlier this month, in which the brightly dressed curator confessed to a shoe obsession and shared the view that “champagne is the only thing you can drink at any time of the day,” Kouoh grew more thoughtful. “I do believe in life after death, because I come from an ancestral Black education where we believe in parallel lives and realities,” she said.

“There is no ‘after death’, ‘before death’ or ‘during life’. It doesn’t matter that much.”

She is survived by her husband, Philippe Mall, by Djibril, and by her mother, Agnes, and stepfather, Anton.

.png) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3