What has just happened, and where are we now? Three long weeks ago, the government began to announce all those cuts to disability and sickness benefits – aimed, they said, at saving £5bn by the end of this decade. Then, only hours before Rachel Reeves’s emergency financial “update”, the seemingly omnipotent Office for Budget Responsibility said that the clawbacks would total significantly less, which prompted the Treasury to not only halve the money paid to new claimants of the incapacity benefit element of universal credit, but freeze its current levels until 2030. Cruelty had followed cruelty: by last Thursday, when it became clear that a record 4.5 million children in the UK are living in poverty, Oxfam was calling these moves “morally repugnant”.

In some quarters, pundits and politicians have moved on from the controversy all this has caused, and are busy speculating about whether the chancellor will soon have to put up taxes. But at the heart of our politics, there is now an inescapable certainty, which will flare up spectacularly when some of the cuts to benefits are put to a parliamentary vote: the fact that Reeves, Keir Starmer and their colleagues are set on immiserating millions of disabled people.

The suffering their decisions are going to cause will materialise soon enough. For now, what the government has triggered is a huge outbreak of the kind of awful fear I heard first-hand last week, when I spoke to someone whose next official benefits assessment might send their family’s income plummeting.

I was put in touch with Kevin by the disability charity Scope. He is 60 years old, and lives in the Croxteth area of Liverpool. In 1994, he was working in a factory that made rubber tubing, where he broke his back. He then found work in the hospitality trade, followed by a job recovering crashed cars, before a benign tumor was discovered in and around his spine, which cannot be removed. “I’ve got nerve compression on my spine,” he told me. “My left leg doesn’t work properly. I’m in pain 24 hours a day. I can’t stand up or sit down for more than five minutes.”

He now receives what official speak calls the enhanced rate of the daily living component of personal independence payment (or Pip), which is about to rise to £110.40 per week. When we first spoke, he said he was terrified that the government’s sudden drive to “tighten” eligibility could drop him to the lower rate of £73.90 – a loss of almost £160 a month. “That’d be a disaster for us,” he said. He already has to make ends meet by regularly borrowing money from relatives.

In fact, he has even more to worry about. His anxiety is focused on the scores awarded in ludicrously bureaucratic Pip assessments on the basis of such “descriptors” as “can prepare and cook a simple meal” or “needs to use an aid or appliance to be able to wash or bathe”. Before we had our second conversation, he had discovered that in the new system, people will have to score a minimum of four points in one of the official categories to receive either rate of the daily living component. “I get threes and twos,” he told me. He is also worried about his 21-year-old autistic son – who also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and epilepsy – and receives the enhanced rate of Pip, but may also not satisfy the new criteria. “I’m terrified,” he said. “My mental health is in the gutter. How do these people sleep at night?”

What Kevin’s predicament most vividly highlights is something everybody well knows: that a lot of the new cuts drive is not about getting people into jobs, but rather the cold imperative to slash money from the so-called welfare budget so that Reeves can meet her fiscal rules. The same callousness is evident in plans to make people under 22 – such as Kevin’s son – completely ineligible for the incapacity benefit part of universal credit, paid to people who have very limited ability to work.

To make things even more wretched, the Pip cuts may actually fly in the face of the employment drive the government insists it wants to pursue, by making it much harder for the sixth of Pip claimants who work to carry on doing so. “If you want to work, the government should support you, not stop you,” Starmer recently said. But tightening entitlements will hack away at the basic economic foundations that disabled people who can work need if they want to enter the labour market. In 15 years of social reporting, one certainty has hit me again and again: that penury and worry make people less likely to get a job, not more. This government is the latest to ignore that fact.

And listen to all the mood music. Darren Jones, the chief secretary to the Treasury, compared the benefit changes to taking some of his children’s pocket money to push them into getting a Saturday job, before admitting that what he said was “tactless”. The health secretary, Wes Streeting, has endorsed the fashionable idea that mental illness is “overdiagnosed”. In the right company, that might be the subject of a nuanced and careful conversation, but from a senior minister in the midst of this political moment, it sounds more like a nasty justification for the cuts: an implied suggestion that it’s OK to take sickness and disability payments away from people, because they may not actually be as sick and disabled as they say.

Meanwhile, a real crisis of public health – manifested in conditions such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes and all the rest – festers away. So does a national emergency centred on a genuine epidemic of anxiety and depression, not to mention long Covid. To enduringly save money, the government could take the ambitious and strategic option of trying to turn these things around. It might also think hard about the deep social issues that keep people out of employment, and look at an idea recently floated by the Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham: turning jobcentres into “live well centres”, dedicated to practical help with debt and poor housing, and their effects on people’s health.

Instead, we get what looks like the worst domestic policy decision made by any postwar Labour government. I wonder how many of the party’s MPs have recently cast their minds back to a rather different kind of thinking, and a book of essays written by that great Labour god, Aneurin Bevan. Published in 1952, it was titled In Place of Fear, and its text was full of observations that sound discomfitingly relevant right now. “Financial anxiety in time of sickness,” wrote Bevan, “is a serious hindrance to recovery, apart from its unnecessary cruelty.” He was making the case for the NHS, but the same point applies to other parts of the welfare state.

And now look: the people in charge of the party Bevan once served are sowing anxiety and horror as a matter of deliberate policy. Which brings us back to the first couple of questions, not so much in the sense of fiscal maths and parliamentary intrigue, but the bleak moral journey Labour has set out on: what just happened, and where are we now?

-

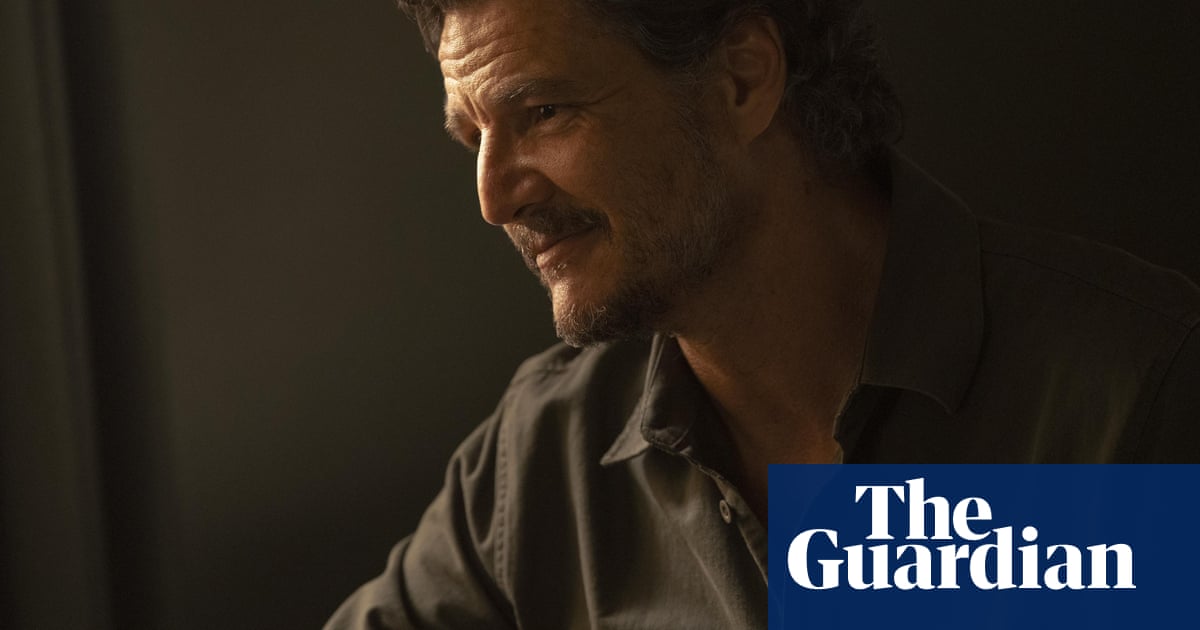

John Harris is a Guardian columnist. He will be talking about his new memoir, Maybe I’m Amazed, with the Observer’s Miranda Sawyer at the Rough Trade shop on Denmark Street in London on 31 March

.png) 1 month ago

30

1 month ago

30