It started with sewage. Few environmental crises evoke such visceral public anger as pumping poo into waterways, but for years, that is exactly what water companies in England and Wales have done in large volumes.

Their failure to build infrastructure, plug leaks and protect nature has infuriated customers who at the same time have struggled with soaring water bills. It has also shocked European neighbours whose publicly owned water companies keep things far cleaner.

Critics say the increasingly sorry state of the UK’s waterways is the result of mismanagement and underinvestment by debt-ridden water companies who were allowed to run wild by toothless regulators.

The problem, as they see it, is the environmental conundrum at the heart of the modern consumer paradigm: public goods such as healthy rivers and clean beaches do not appear on company balance sheets. Why should corporations – which have a duty to create value for their shareholders – look after public goods? And if governments won’t force them to, should we really expect them to look after the environment?

In this case, after a landmark report into the troubled sector on Monday, the government announced it would combine the powers of four water industry watchdogs – which had competing economic and environmental aims – into one entity with oversight for the sector. It promised “strong ministerial directives” and an end to its light touch approach.

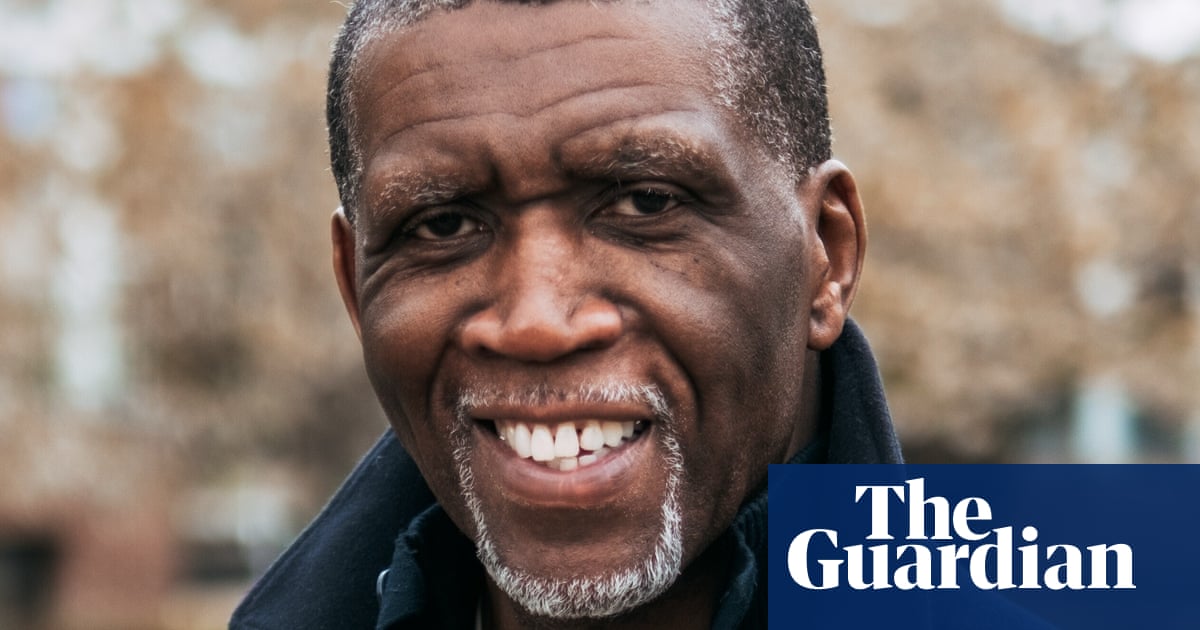

“A single, powerful regulator responsible for the entire water sector will stand firmly on the side of customers, investors and the environment, and prevent the abuses of the past,” said Steve Reed, the UK environment secretary.

The adopted proposal is just one of 88 recommendations from a report by an independent water commission– the bulk of which the government will consider over the summer – and the response from environmental experts has so far been muted.

Hannah Cloke, a hydrologist at the University of Reading, said water industry reforms were “long overdue and badly needed” but warned against spending years setting up new structures while rivers stay polluted and reservoirs run dry.

“The real challenge isn’t designing better systems on paper – it’s getting companies to actually fix leaking pipes, stop dumping sewage, and build the infrastructure we need,” she said. “Less reorganising, more doing.”

The report contains a number of recommendations that could help improve water quality and manage its supply, such as better third-party monitoring, new infrastructure standards, compulsory smart meters and a ban on wet wipes with plastic. It considers drawing from new EU rules to make polluters pay for the extra treatments needed to clean up emerging micropollutants, which could eventually include long-lasting Pfas and microplastics.

The report also calls for the updating of existing environmental laws, in addition to overhauling the regulators. The proposed “streamlining” includes setting a new long-term target for the health of water bodies in England and Wales – though the move might tempt ministers to lower ambition, given that the existing targets are set to be missed.

Mark Lloyd, chief executive of the Rivers Trust, said it was understandable that “many people will have wanted this report to go further” but that he believed the recommendations, if implemented, would lead to a “dramatic improvement” in the water environment and more cost-effective delivery.

Most of all, though, the report has also come under fire for what it has left out.

Adrian Ramsay, co-leader of the Green party, compared the proposed regulatory changes to “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic”.

“Not only that, but the majority of the public are going to be expected to pay more in bills, as we watch the industry continue to sink under the failed model of privatisation,” he said. “The government deliberately left out the option of public ownership from the review, but that’s the only real way to get the water industry to clean up its act.”

That outcome isn’t guaranteed. When the water companies were privatised in 1989, the UK was regarded as “the dirty man of Europe”. A trip to its beaches shows it has come full-circle.

.png) 3 months ago

55

3 months ago

55