When a schoolboy running on a beach on the island of Sanday in Orkney last year came across the timbers of a shipwreck that had been exposed after a storm, local people knew the ship might have an intriguing history.

Residents of the tiny island at the edge of the Scottish archipelago are familiar with ships that have come to grief in stormy seas, hundreds of shipwrecks having been recorded there over the centuries.

But this large section of oak hull, its boards carefully knitted together by wooden pegs, appeared particularly well built and was obviously not recent. The question was, how old was the ship – and what else could they learn about it?

Eighteen months after that discovery in February 2024, archaeologists and local volunteers have managed to identify the ship and to piece together the surprising history of a vessel that witnessed some of the most dramatic events of the 18th century before finally being wrecked off Sanday in 1788.

Thanks to detailed timber dating and historical analysis, experts are confident the hull belonged to HMS Hind, a 24-gun Royal Navy frigate that was built in Chichester in 1749 and went on to have a remarkable career.

Despite its sticky end, the Hind was “an amazingly long-lived and lucky ship”, according to Ben Saunders, a senior marine archaeologist at Wessex Archaeology, who led the project alongside Historic Environment Scotland (HES) to recover and identify the vessel’s remains.

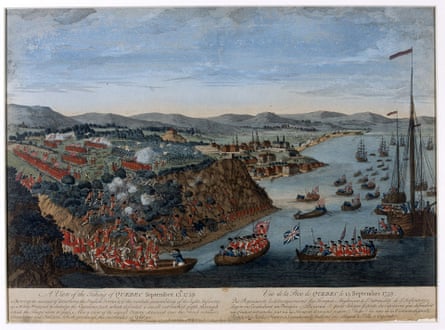

The ship, naval records show, served off the coast of Jamaica in the 1750s and took part in the sieges of Louisbourg (1758) and Quebec (1759), when the British defeated French forces in Canada during the seven years war. It was among the British fleet in the American revolutionary war of the 1770s and then served for a decade as a training ship in the Irish Sea, before it was decommissioned and sold off to become a 500-tonne whaling ship in the Arctic Circle.

It was in this guise, under the new name of The Earl of Chatham, that the ship was wrecked by a North Sea storm on 29 April 1788. Even then, its luck did not desert it – all 56 people onboard survived, a snippet in the Aberdeen Journal records.

Identifying the vessel posed a challenge for present-day archaeologists, however. The hull, measuring 10 metres by 5 metres (about 33ft by 16ft), had been well preserved under the sand, allowing multiple wood samples to be sent for dendrochronological analysis. Experts found that the wood had originated in southern and south-western England, and that the earliest sample had a clear felling date of spring 1748.

Saunders and his colleagues then worked closely with the community of Sanday, for whom shipwreck timber has been an important source of wood for centuries. The island is largely treeless, and “some of the people we’ve been working with have half their roofs held up with masts and deck beams”, he says. “It’s incredible.”

A date in the mid-18th century was not only interesting but helpful, says Saunders, “because this is when you’re starting to get the bureaucracy of the British state kicking in, and a lot more records surviving”. A group of 20 volunteer researchers pored through maritime archives, government shipping registers and news sheets to pinpoint the right vessel among at least 270 known to have foundered on Sanday.

after newsletter promotion

“[The islanders] also brought a lot of their own experience,” says Saunders. “You’ve got a lot of people in Orkney who are connected to the sea anyway. That meant we could collate this massive amount of data and start saying: ‘Right, that ship is too small, that ship was built in the Netherlands, no, not that ship.’”

Eventually, the records led the researchers to the Hind and its second life as a whaler when Britain’s early Industrial Revolution was relying more heavily on the products of whaling.

The timbers salvaged from the shoreline are now being preserved underwater at the Sanday heritage centre while a long-term home is under discussion.

Alison Turnbull, the director of external relationships and partnerships at HES, says the “rare and fascinating story” of the ship’s identification “shows that communities hold the keys to their own heritage. It is our job to empower them to make these discoveries.”

Saunders says what he really enjoyed about studying this wreck was “that we’ve had to do this detective work”, combining the highly technical scientific analysis with scrutiny of a wealth of archive material. “We’re really lucky to have so much archive material, because of the period and because of where it wrecked in Orkney. It’s been very satisfying.”

.png) 3 months ago

53

3 months ago

53