Vast pipelines cross the endless dunes of northern Chile, pumping seawater up to an altitude of more than 3,000 metres in the Andes mountains to the Escondida mine, the world’s largest copper producer. The mine’s owners say sourcing water directly from the sea, instead of relying on local reservoirs, could help preserve regional water resources. Yet, this is not the perception of Sergio Cubillos, leader of the Indigenous community Lickanantay de Peine.

Cubillos and his fellow activists believe that the mining industry is helping to degrade the region’s meagre water resources, as Chile continues to be ravaged by a mega-drought that has plagued the country for 15 years. They also fear that the use of desalinated seawater cannot make up for the devastation of the northern Atacama region’s sensitive water ecosystem and local livelihoods.

Water extraction has caused water table levels to drop, endangering springs, wetlands and surface water sources that support biodiversity and are vital for local crops and livestock. “Several wetlands have dried up completely, and the vegetation has diminished considerably,” says Cubillos. The community of Peine lies within a salt flat, where a delicate ecological balance makes the region highly vulnerable to any changes in climate. Cubillos says mining has exacerbated the effects of the climate crisis, severely depleting the community’s groundwater reserves. “The mining activity has made the area unsuitable for cattle grazing.”

The mega-drought is considered the most prolonged and widespread in a century, and the local population and mining companies are fighting for the right to water in the Atacama desert, the driest place on Earth, where the world’s largest copper and lithium deposits are located.

The lack of rainfall has had profound effects on Chile’s water resources, agriculture and ecosystems and is severely depleting its freshwater reserves in the Atacama region. Even mining operations have occasionally been forced to stop due to water shortages.

In December, Escondida’s majority owner, the Australian mining firm BHP, the US-based Albemarle and Chilean firm Zaldívar were ordered to pay an unprecedented $47m fine (£34.5m) for depleting the Monturaqui-Negrillar-Tilopozo aquifer and damaging surrounding vegetation.

The environmental court of Antofagasta ruled that the damage caused by the three companies “negatively affects the Indigenous community of Peine, altering their systems of life and traditions”. It ruled that the companies had exceeded the legally permitted limits on groundwater extraction, resulting in a decline of the water table by more than 25cm – an unsustainable amount for the salt flat ecosystem, according to the court.

Chile’s water authority had already raised concerns in 2018 over Escondida’s water extraction. In 2022 Escondida appealed an $8.4m fine for non-compliance over this issue, but it was rejected.

The environmental court’s decision came after a negotiated agreement between the Indigenous community, the Chilean government and the companies involved. The fines are earmarked for environmental remediation, which in some cases includes investment in desalination.

The mining sector is increasingly turning to the sea. About 30% of the water used by Chile’s mines now comes from seawater – desalinated or untreated – according to the national mining association. BHP says it has invested $4bn (£2.94bn) in desalination infrastructure in recent years. As a result, the company says, it ceased extracting water from the Peine wetland in 2019.

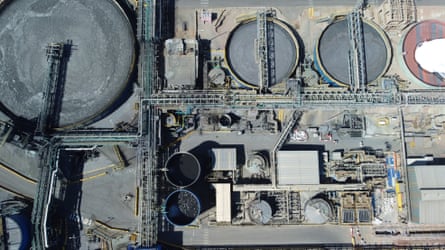

Its desalination plant in the coastal city of Coloso, about 170km (105 miles) from the mine, is the largest in Chile by capacity. “The company’s first desalination plant opened in 2006, underscoring our pioneering role in the mining sector,” BHP says.

Albemarle has also told the Guardian that it no longer uses groundwater from the reserve in its operations. “While our company has never been a major water user in the area, this step is part of our long-term sustainability efforts on the Atacama salt flat,” the company’s communications manager says.

Albemarle has further clarified that the use of seawater to remediate environmental damage is not included in the formal agreement by the court, though its website highlights ongoing investments in desalination.

Zaldívar has declined to comment.

after newsletter promotion

Cubillos, who took part in the negotiations, acknowledges the shift. “It’s positive that companies have stopped exploiting groundwater reserves,” he says. “However, the desalinated water does not reach our lands.”

The three companies that the court found responsible for depleting Peine’s groundwater produce roughly half of Chile’s copper and a third of its lithium.

Mining accounts for about a fifth of Chile’s gross domestic product, and minerals – particularly copper and lithium, which are essential for the global green transition – are the country’s main exports. Chile supplies about 13% of the copper and 80% of the lithium carbonate and refined lithium imported into the EU.

Lithium is critical for electric vehicle batteries, while copper underpins most renewable energy technologies and infrastructure. The global green transition is projected to substantially increase demand for copper and lithium. For Chile, this implies escalating water requirements for mining operations.

Despite advances in desalination, mining remains a major consumer of fresh water, accounting for about 50% of regional reserves in the north. Chile’s ministry of mining projects that total consumption of water will go up by about 20% by 2034.

Desalination and transporting seawater inland also come with environmental costs. These are energy-intensive processes, and studies forecast that CO2 emissions from Chile’s desalination plants could reach up to about 700,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually by 2030 – about the same as Antigua and Barbuda.

Only a small share of these plants operate on renewable energy, according to Sebastián Herrera-León, an assistant professor at the University of O’Higgins. “Currently, desalination plants in Chile are powered by the national grid, which draws from both fossil fuels and renewables,” he says.

He identifies two ways forward: either desalination plants must integrate dedicated renewable energy sources, or the national energy grid must complete its transition to renewables.

Desalination may also transfer environmental risks from the desert to the ocean. In Antofagasta, a coastal town in northern Chile near where Escondida’s desalination plant and port are located, local fishers have already noticed changes.

“Fish populations are dying. Escondida’s port has long polluted the sea, and the desalination plant makes things worse,” says fisher Nelson Fornedod Gutiérrez, 82.

Marine biologist Elizabeth Soto of the NGO Terram says that brine discharge from desalination poses a threat to aquatic biodiversity. “Improved spatial planning is essential for desalination plant siting. Constructing facilities along the entire coastline without accounting for environmental impacts is unsustainable,” she says.

Mining companies own 17 of Chile’s 24 operational desalination plants, with more planned along the Pacific coast. About 75% of the country’s desalination capacity serves the mining sector.

While desalinated seawater has eased pressure on dwindling inland sources, the Indigenous community of Peine remains wary. The damage may already be irreversible, they fear, damaging the salt flats and their waters, which are as vital as they are sacred to the Lickanantay people.

“We continue to resist mining companies,” says Cubillos, “to assert that our Indigenous culture and worldview remain alive.”

.png) 2 months ago

94

2 months ago

94