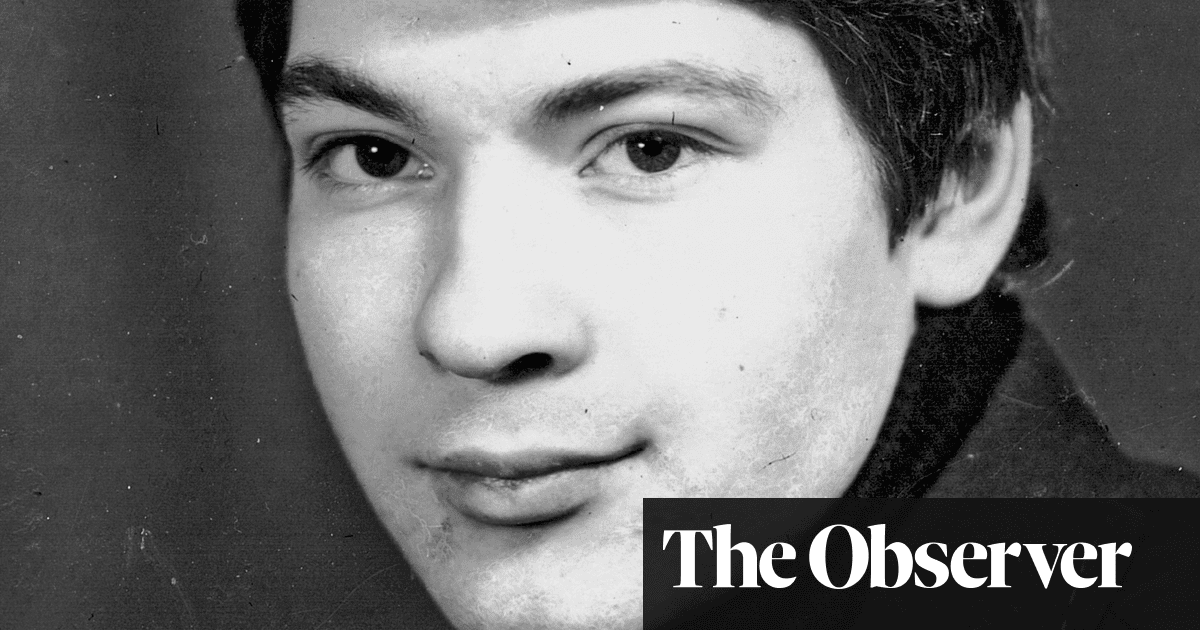

My brother held his phone up to my ear. “You’re gonna find this creepy,” he warned. An Instagram reel showing a teenage boy at a rally featured a voiceover in the style of a news broadcast. A calm, female voice, with an almost imperceptible Mancunian accent, said: “The recent outcry from a British student has become a powerful symbol of a deepening crisis in the UK’s educational system.” I sat bolt upright, my eyes wide open.

As a presenter for a YouTube news channel, I was used to hearing my voice on screen. Only this wasn’t me – even if the voice was indisputably mine. “They are forcing us to learn about Islam and Muhammad in school,” it continued. “Take a listen. This is disgusting.” It was chilling to hear my voice associated with far-right propaganda – but more than that, as I dug further into how this scam is perpetrated, I discovered just how far-reaching the consequences of fake audio can be.

AI voice cloning is an emerging form of audio “deepfake” and the third fastest-growing scam of 2024. Unwitting victims find their voice expertly reproduced without their consent or even knowledge, and the phenomenon has already led to bank security checks being bypassed and people defrauded into sending money to strangers they believed were relatives. My brother had been sent the clip by a friend who had recognised my voice.

After some digging, I was able to trace it back to a far-right YouTube channel with around 200k subscribers. It was purportedly an American channel, but many of the spelling errors on the videos were typical of non-native-English-speaking disinformation accounts. I was horrified to find that eight out of 12 of the channel’s most recent videos had used my voice. Scrolling back even further, I found one video using my voice from five months ago showing a view count of 10m. The voice sounded almost exactly like mine. Except there was a slightly odd pacing to my speech, a sign the voice was AI-generated.

This increasing sophistication of AI voice-cloning software is cause for grave concern. In November 2023, an audio deepfake of London Mayor Sadiq Khan supposedly making incendiary remarks about Armistice Day was circulated widely on social media. The clip almost caused “serious disorder”, Khan told the BBC. “The timing couldn’t have been better if you’re seeking to sow disharmony and cause problems.” At a time when trust in the UK’s political system is already at a record low, with 58% of Britons saying they “almost never” trust politicians to tell the truth, being able to manipulate public rhetoric has never been more harmful.

The legal right to own one’s voice falls within a murky grey zone of under-legislated AI issues. TV naturalist David Attenborough was at the centre of an AI voice-cloning scandal in November – he described himself as “profoundly disturbed” to discover his voice being used to deliver partisan US news bulletins; in May, actor Scarlett Johansson clashed with OpenAI after a text-to-speech model of its product, ChatGPT, used a voice Johansson described as “eerily similar” to her own.

In March 2024, OpenAI delayed the release of a new voice-cloning tool, deeming it “too risky” for general release in a year with a record number of global elections. Some AI startups that let users clone their own voice have introduced a precautionary policy, allowing them to detect the creation of voice clones that mimic political figures actively involved in election campaigns, starting with those in the US and the UK.

But these mitigation steps don’t go far enough. In the US, concerned senators have proposed a draft bill that would crack down on those who reproduce audio without consent. In Europe, the European Identity Theft Observatory System (Eithos) is developing four tools to support police in identifying deepfakes, which they hope will be ready this year. But tackling our audio crisis will be no easy feat. Dr Dominic Lees, an expert in AI in film and television who is advising a UK parliamentary committee, told the Guardian: “Our privacy and copyright laws aren’t up to date with what this new technology presents.”

If trust falling in institutions is one problem, creeping distrust among communities is another. The ability to trust is central to human cooperation in our increasingly globalised, increasingly intertwined personal and professional lives – yet we have never been so close to undermining it. Hany Farid, a professor of digital forensics at the University of California at Berkeley, and an expert in detecting deepfakes, told the Washington Post that the consequences of this audio crisis could be as extreme as mass violence or “stealing elections”.

Could there be any upside to this newfound ability to readily clone voices? Perhaps. AI voice clones could allow us to seek comfort by connecting with deceased loved ones, or help give a voice to those with medical conditions. The American actor Val Kilmer, who has had treatment for throat cancer, returned in 2022 for Top Gun: Maverick with a voice restored by AI. Our ability to innovate may serve those with nefarious aims, but it also serves those working for good.

While I willingly shared my voice on screen when I became a presenter, I did not agree to sign away this integral, precious, part of myself to anyone who wants to use it. As broadcasters, we sometimes worry about how a cold or winter virus might impact our recordings. But my recent experience has given another, far more sinister meaning to the concept of losing one’s voice.

-

Georgina Findlay is a writer and presenter at the YouTube channel TLDR News

.png) 3 months ago

89

3 months ago

89