What will it take to drag the Church of England into the 21st century? It has been a monumental year for the established church in this country, with the resignation of Justin Welby as archbishop of Canterbury and the interim arrangements for his succession in a state of flux and confusion.

As we begin the new year, it’s natural to stop and reflect on what has passed and where we’re going. Sadly, within the church, we seem incapable of learning from our mistakes. Those we look to for leadership repeatedly fail, leaving us to wonder where to go for ethical and moral guidance. In the midst of unprecedented uncertainty, far from offering stability and hope, trusted institutions seem to be collapsing around us.

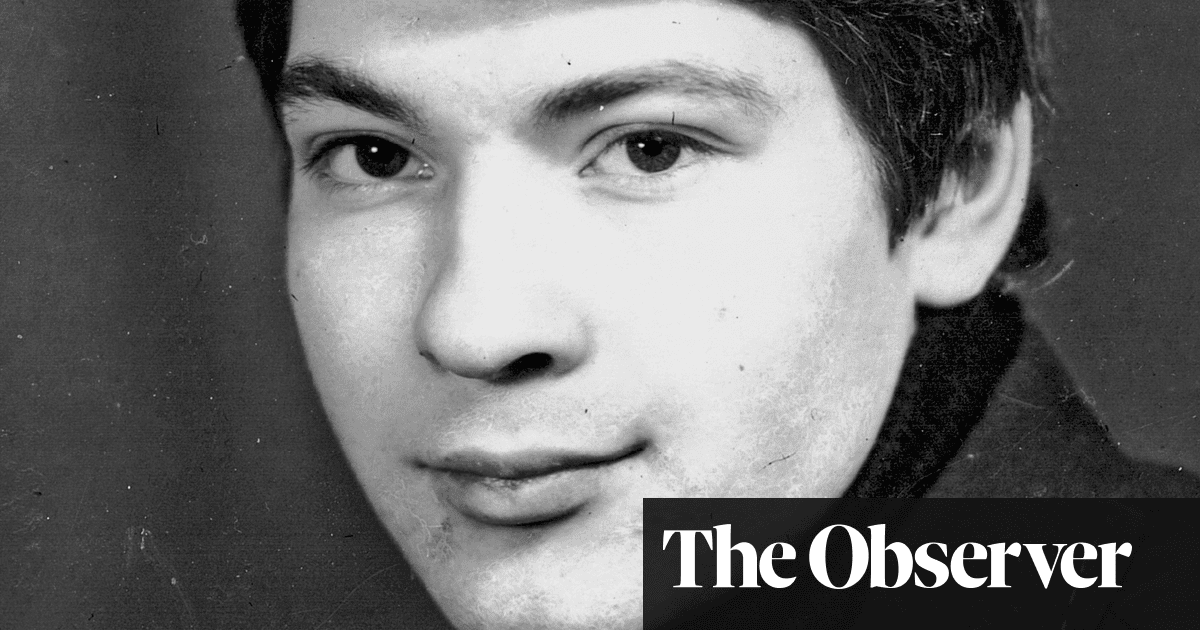

My friend’s funeral earlier this year left me with a similar feeling of loss, on multiple levels. The Rev Capt Katie Watson was someone whose life touched many hundreds, if not thousands, of people in Newcastle and the north-east of England through her work as a hospital chaplain. But a reference to her “partnership” of two decades during the service reminded me of how little has changed since the 1980s and 90s, when same-sex partners were forced to lie or pretend.

I witnessed my friend Emily stand next to Katie’s coffin with their two teenage children, and honour the woman with whom she had shared nearly 20 years of her life. They were a family – and at the heart of their family was a loving, faithful union that had seen them all through the worst and best of times.

Yet Emily and Katie were not married. They could only enter a civil partnership because they were both following their vocation to be ordained ministers in the Church of England. Many people would find their faith unfathomable. Others may simply say with cold legalism “that’s the rules”.

I was confirmed in the Church of England but left during the 1990s as I found it impossible to reconcile my faith and sexuality within the church. At that time, being gay was widely seen as a distortion of God’s intention for the world (expressed in the infamous US evangelical slogan “God created Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve”).

I spent 15 years in lay ministry (a role within the church for those who are not ordained). It was through Metropolitan Community Churches, an inclusive movement founded within the LGBTQ+ community in the US in response to the Aids crisis, that I met Emily and Katie, and watched them bravely follow their vocations, trying to change “the system” of the Anglican church from within. They, along with countless others like them, did so at huge personal cost. In the light of recent disclosures and resignations, many are now wondering what all this sacrifice was for.

Katie’s funeral reminded me of this. It also forced me to remember a time when those in same-sex relationships could not legally make decisions for one another if we were sick or dying. We had no pension rights or legal powers of inheritance. Relatives could and did step in at times of crisis, ignoring the wishes of lifelong, devoted partners about the care that someone should receive or where they should live.

We may think those dark times are behind us in the UK, but we are still treated as second-class citizens by the church. In 2018, I agreed to take part in the Living in Love and Faith consultation – the Church of England’s discernment process about identity, sexuality, relationships and marriage. It was a long and painful process over many years, involving senior figures, bishops, lawyers, people of good will and conscience who came up with many complicated theological reasons to argue why discrimination should continue. These centred on the idea of being “gay” as not an identity but a temptation (with the logic that same-sex attraction is like any other temptation that must be resisted, and possibly even “cured”). For some of us who participated, it was a matter of life and death: for others, an intellectual problem or even an inconvenience.

At the end of this process, I felt sullied and compromised. Some small concessions were made to accepting LGBTQ+ people within the Church of England at General Synod in 2023. So now we may be blessed in church, though not married in church. Lay people may now enter into same-sex marriages (although they may not do so in an Anglican church), but Anglican clergy are still not able to do so. This compromise satisfies no one: a concession that goes too far for some, and not far enough for others.

If this hypocrisy and discrimination, some might say obsession, over sexuality continues, the Anglican communion will simply cease to exist. Churchgoing numbers are declining rapidly, and many people simply regard the C of E as an irrelevance. Considering the “unworthiness” of anyone who has sex or cohabits outside marriage, divorces or engages in loving relationships with the “wrong” person, really there are very few options available for the majority but to leave the church or ignore it. Most people rightly look at the record of Catholic and Protestant churches in relation to the repeated child abuse scandals that continue to be exposed and have concluded that the moral authority of religious organisations has been completely lost.

It’s not good enough that my widowed friend bravely stood there at the funeral of her wife (in everything but law) as the surviving “partner”. It’s not good enough that the worth of the most faithful example of Christ-like devotion I have witnessed in a couple can be treated so slightly. It will not be ok in 2025 to hide behind excuses, and to say that some relationships simply aren’t as good as others. Let’s hope recent events have been a wake-up call that the church simply cannot ignore: it has to change.

The church says we are all broken in our humanity and redeemed by love. Katie actually lived this out. Her death demands a revolution, one that will break through hypocrisy and expose the vapidity of this rapidly dying institution. The church may die, but her love will live on.

-

Helen Berry is an author and former lay minister with the Northern Lights Metropolitan Community Church, Newcastle upon Tyne

.png) 3 months ago

42

3 months ago

42