Alan Alda never expected this. The 89-year-old is back topping the charts with an update of his film The Four Seasons. In 1981, Alda wrote, directed and starred in the movie about three inseparable couples who holiday together every quarter until divorce, envy and angst intervene.

Now the film has been turned into a TV series by Tina Fey, with Alda as a producer and, at the time of writing, it is the fourth most watched show on Netflix. “It’s really interesting to have my work appeal to a new generation of very smart writers,” he tells me on a video call from New York. What gave him even more pleasure was watching a screening of the original movie a couple of weeks ago. “The people were laughing at the same things they were 44 years ago. And just as heartily. It was so good to see that the point of view wasn’t outdated.”

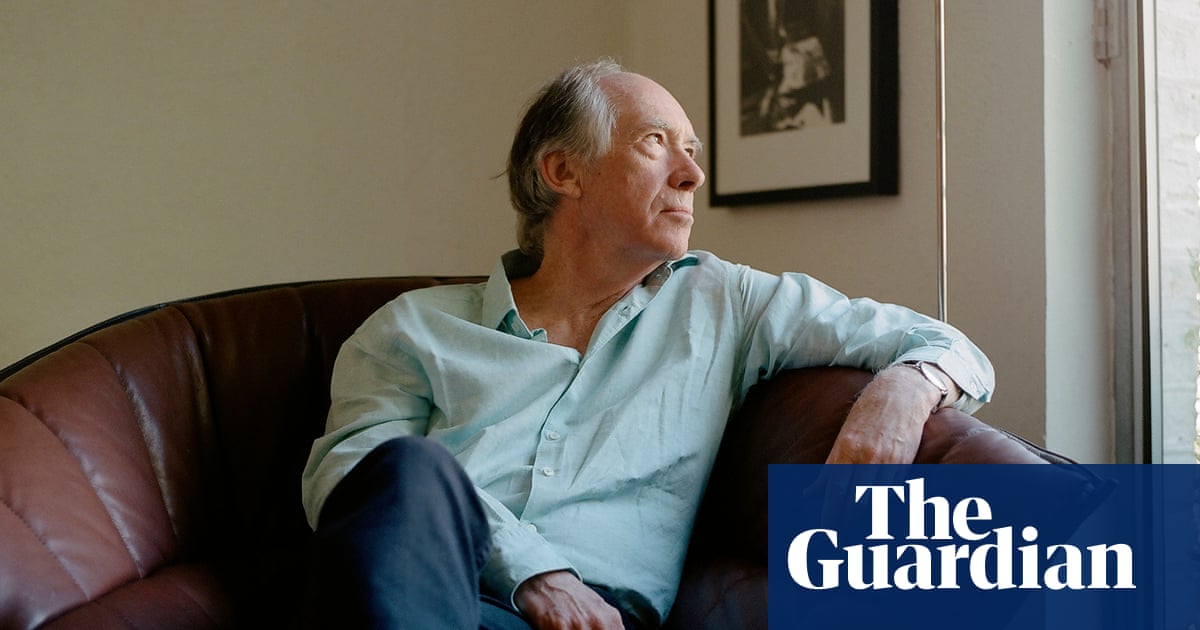

Alda makes a cameo appearance at the start of the TV series as Don, an elderly man with Parkinson’s disease. “At the moment, I can play anyone with Parkinson’s,” he says. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2015 and went public about it in 2018. His shakes are now pronounced, the gorgeous jet-black hair is long gone, and he looks his age. But as soon as his face breaks out into that familiar cheek-to-cheek grin, he becomes boyish again. Not quite the Hawkeye of yesteryear, but a venerable facsimile.

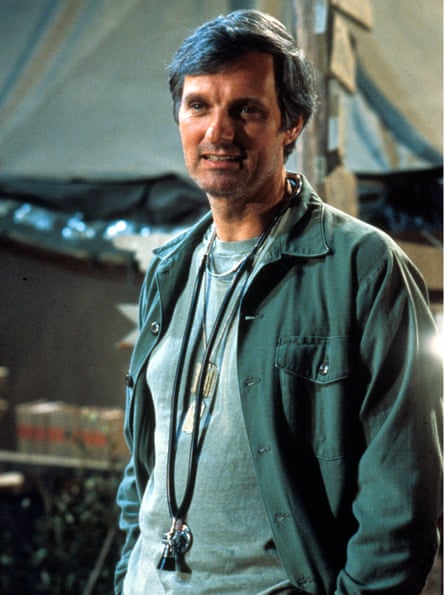

Captain Benjamin “Hawkeye” Pierce of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital unit is the character that made Alda’s name, in M*A*S*H, the TV war comedy-drama set in 1950s South Korea. Hawkeye is a hard-drinking, skirt-chasing, war-hating, wisecracking surgeon, brimming with principle and soul. As for Alda himself, he has the principle and soul, but less of the boozy priapism. In fact, he is better known as an early champion of equal rights for women, and a poster boy for marriage, celebrating 68 years and counting with his wife, Arlene. In a poll of American women in the early 1990s, participants were asked to nominate their ideal man. Jesus was first with 14%, Mahatma Gandhi second with 8% and Alda third with 7%.

At an age when many of us would barely remember retiring, Alda is phenomenally busy. As well as the acting and producing, there are the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science and a podcast series, Clear + Vivid, which he has presented since 2018. Alda is a warm and generous presenter, and in more than 350 episodes he has interviewed a fascinating range of people, including AI guru Jaron Lanier, Paul McCartney, members of the M*A*S*H cast, astrophysicist Mario Livio, and Michael J Fox about how he has coped with his Parkinson’s.

At the end of each episode of Clear + Vivid, he asks his guests seven questions, including, is there anybody they can’t empathise with? Communication and striving for empathy have always been at the heart of his work. Whether as a director, actor or writer he has always opted for dramas about relationships where people talk their way to a resolution or otherwise.

Alda was born Alphonso Joseph D’Abruzzo, in New York. His father, an actor and singer of Italian heritage who appeared in burlesque and then became a film star, adopted the name Robert Alda. His mother, Joan, a beauty pageant winner later diagnosed with schizophrenia, was of Irish descent. Through his childhood the family travelled around the US, following his father where the work took him. “He was very famous but he hardly made much money because that was at a time when Warner had those seven-year contracts.”

In the opening sentence to his fine memoir Never Have Your Dog Stuffed, he writes: “My mother didn’t try to stab my father until I was six, but she must have shown signs of oddness before that.” Does he think his mother’s condition made him more empathetic? “I’ve thought about it a lot, but I haven’t traced an interest in empathy to that.” A typical Alda response. He is not one for easy answers. “It may be true. What I was aware of was that I had to constantly observe her. When she told me something, I had to figure out whether this was reality or just her reality. She would point to cracks in the wall and say there were cameras in there taking our picture.”

His mother taught him how to improvise – something that has remained important to him in work and life. He had to know how to react to whatever reality she was in for his own safety. She was eventually diagnosed and hospitalised when he was a student. “I was in college in Paris, Dad was making a TV series in Amsterdam and Mum was running down the hotel corridor one night naked banging on doors.”

At the age of seven, Alda was diagnosed with polio. He was put on a strict swimming regime. “As part of the therapy, I swam seven hours a day. I fully recovered.” Did he end up a strong swimmer? He smiles. “No, but it gave me a lot of stamina.”

As a young boy, Alda performed with his father in the less risque burlesque sketches. Did he always want to be an actor? He shakes his head. “I wanted to be a writer when I was eight, and it was only later in life, when I was nine, that I wanted to be an actor.” His quips are so dry they’re easy to miss.

He starts coughing, and drinks from a glass of water that he holds with quivering hands. “The problem is the pollen count is very high here. I’m very allergic to pollen.”

How is his Parkinson’s? “A little shaky!” He smiles. How does it affect him? “Not much. I just have to plan for the fact that everything takes three times longer to do or more. Getting your clothes on, taking your pills. I have to type every email three times before I stop saying rude things. I write emails to women I don’t know and unless I check, before my signature there are six Xs.” Would he normally send kisses? “Not to somebody I don’t know!” he says, appalled. “Dr Parkinson has fun with the keyboard.”

Does it annoy him? “I rarely get upset at it because I know it’s reality. It’s much easier to take reality than wish for something you haven’t got. I fell into this way of thinking that if a button takes too long to button, I have to find other ways to do it. And eventually if I land on a way that makes the button go through the buttonhole it’s a little victory for me, and I feel like a million bucks.” He pauses. “It sounds like something I read in a self-help book, but it isn’t. It’s just the way I found myself reacting, and I’m very glad that I did.”

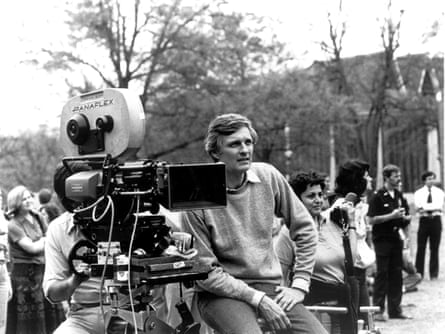

At 21, Alda married Arlene, a professional clarinettist. When M*A*S*H started in 1972, he was already in his mid-30s, the father of three daughters, and a respected theatre actor. Initially, he didn’t want to accept the role because it would take him away from the family for too long. In the end, he starred in every episode over 11 seasons and 11 years, directing 32 episodes (more than anybody else) and writing 19.

He learned so much from the show, not least how best to work with people. In between shoots, rather than disappearing to dressing rooms, they sat in a circle, laughing, chatting, making fun of each other. “When they called us to the set, we still had that connection, and it came out in between the lines we were saying to each other, so there were people really talking to each other.” Not only was M*A*S*H a huge success, it made him extremely wealthy. At the start, he earned good money – $10,000 an episode. By the end, he was on $250,000 a show. The final episode was watched by 106 million people in the US, still a record for a scripted TV series.

The money gave him the freedom to do what he wanted with his life, not least develop his own projects. While still working on M*A*S*H, he made The Four Seasons, which is the film that means most to him because it’s so personal. “Much of my family was engaged in it. Arlene wrote a book about the making of it, she did the photographs for one of the characters, two of our daughters acted in it. It was about incidents that had occurred among my close circle of friends.”

I ask if there’s a secret to a long, happy marriage. No, he says. “I don’t think it can be put into a nugget. It involves being aware of how much you love the person not only in tender moments but also when you’re screaming at each other. Arlene has a simpler explanation.” What’s that? “When people ask her what’s the secret of a long marriage she says a short memory.”

How is she? A huge sunny smile envelops his face, and his eyes narrow to a joyous squint. “She’s great. I had to stop her from playing the piano so we could talk. She practises at least two hours every day. She doesn’t have the breath now for the clarinet so she’s gone back to the piano for the first time in decades.”

The pollen has got to him, and I’m worried about his coughing. He seems tired and we have already been talking for well over an hour. So we say our goodbyes. He tells me how good it has been to chat. And it has, but about five minutes later I realise there is so much more to talk about. I email his publicist, and ask if there is any chance of a catch-up.

Two days later, we are back on Zoom, and he is talking about the great directors he has worked with. Alda got his only Oscar nomination playing a sleazy senator in Martin Scorsese’s 2004 film The Aviator. What did he learn from Scorsese? Positivity, he says. “Everything he had to say was filled with praise. ‘That was great what you got! Maybe next time try a bit more of this, but just great!’ Later in the day you find out he didn’t like what you did at all!” He laughs. “He’s a very nice guy.”

Alda made three films with Woody Allen – Everyone Says I Love You, Crimes and Misdemeanors and Manhattan Murder Mystery. Which is his favourite? “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” he says instantly. Alda is memorable as the pompous documentary-maker with a fine line in cant. What did Allen teach him? “I don’t know what I learned from him because he didn’t talk much. You and I have spoken more than he spoke making three movies!”

A number of actors have said they won’t work with Allen again after his adoptive daughter accused him of sexual abuse. Would Alda? “Yes I would. If a court has made a decision, I’m willing to go along with that. But I’m not the court. I’m glad Harvey Weinstein went to jail. He was tried and convicted. But I’m not going to punish somebody who hasn’t gone through that process. People have to make up their own mind about what’s reasonable and follow their feelings.”

In 2006, Alda won an Emmy for playing Arnold Vinick in The West Wing, a moderate Republican presidential candidate who ends up as secretary of state in a Democrat government. Could he see something like that happening in real life? “No. No. Even at that time he was a fantasy.”

How does he feel about the US now? “We’re in a time of crisis and I hope we can work our way out. I hope there are enough people of good will and conscience and courage to take us out of it. People on all sides. These are the times that try men’s souls.” Has he ever known a time like this in his life? “No! Never. Never. No. I don’t think anybody in our country has.”

Can he empathise with Donald Trump in any way? “Every once in a while I wonder if the desire to tear down everything that some of us over here have actually does come from a grievance that ought to be addressed. If there’s anything that has been overlooked or underserved among the population that wants to tear everything down, then they ought to be served properly. If on the other hand it’s just racism, misogyny and anti-science, then we need to reach out to one another for some education.”

He catches his tone, and says he doesn’t like it. “To say I’m going to educate you is a little top heavy,” he says apologetically. “Exploring the data and trying to understand what’s reality and what isn’t would be helpful for everybody.” Is Trump a racist? “Well, he certainly does racist things and says racist things.” A misogynist? “By his own mouth he is.” Anti-science? “I think a person who suggests that taking horse pills or swallowing bleach will help Covid is anti-science. Science has been defunded now a lot in the US, and that’s going to have serious consequences for people’s health and for the security of the country.”

Does he worry the US is moving towards fascism? Silence. He eventually answers. “Authoritarianism, clearly,” he says.

Yet, despite everything, he feels optimistic about the future. “I’ve got a tremendous amount of confidence that the world is going to work out for us humans.” After all, he points out, species tend to last around 2m years, and we’re only 300,000 years old. “It would be great if we could exist 2m years.”

I can hear a piano in the background. Is that Arlene? “Yes, she’s so absorbed in her music. She’s playing Beethoven.” I tell him I’ve been thinking about something he said the other day – that he and Arlene remember how much they love each other when they’re having a screaming match. Do they scream at each other often? “No, we make each other laugh. But you can’t have a marriage that goes on for a long time without strong disagreements.”

Is it unusual for a couple in his business to have stayed together so long? Not really, he says. “You know, we’ve been good friends for decades with Mel Brooks and Rob Reiner. Both their wives are dead now, but both had very long marriages. And there are plenty of friends who have been married for 50 or 60 years.” He pauses, and I can see his mouth creasing into that sunny smile. “To multiple people, but at least they were only married to one at a time.” I burst out laughing. Have you ever said that before? “No, I don’t think I have!” And he sounds so happy.

.png) 3 months ago

138

3 months ago

138