Julian Kingma was afraid of dying.

In this regard, perhaps the award-winning portrait photographer is not much different from the rest of us. But Kingma’s obsession with mortality had stalked him since childhood – and spilled over into adulthood.

Sometimes, in his work, he would be sent out on end-of-life stories, documenting terminally ill people. He was fascinated by people who wanted to end their lives, long before Victoria became the first Australian state to introduce voluntary assisted dying (VAD) legislation in 2017.

In 2021, he listened to Better Off Dead, a podcast by Andrew Denton, founder of the assisted dying charity Go Gentle. Denton was telling the stories of some of the first people to access the landmark Victorian laws.

For Kingma, it was a lightbulb moment. Hearing the stories was one thing – putting faces to them was another. He rang Go Gentle. The collaboration that followed, a book-length photo essay called The Power of Choice, was life-changing.

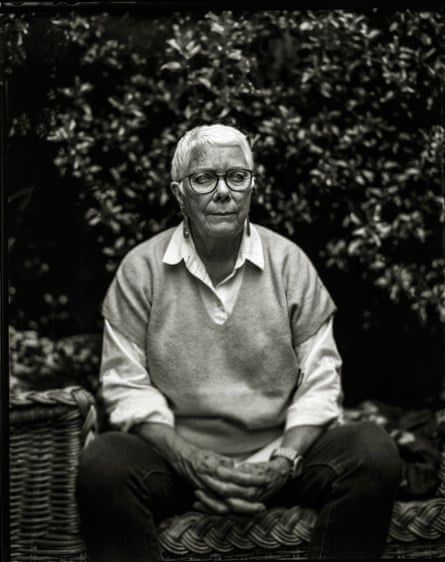

Kingma travelled the country for more than a year, sitting, staying with and capturing people who had accessed assisted dying, along with their doctors, carers and families. The experience challenged him to look death in the eye – and helped alleviate some of his own anxiety.

It helped that his subjects made him welcome. They wanted to talk. “I was surprised by their candour, and about how important it was to them that I told their story,” Kingma says. “There wasn’t a single person who shied away.”

What Kingma was more surprised by was the level of independence they gave him at the most intimate and vulnerable time in their lives. “I wanted to involve them in a way that they felt like they were in control, so it was a bit of a dance that I was leading,” he says.

But no one he photographed told Kingma how to go about his work or insisted on vetting their images. Sometimes, he offered them the chance to view their portraits, only to be refused. Some feared they’d change their minds when confronted with their own decline in black and white.

Some of the stories are uplifting. If you were to idealise a good death, it might look a bit like the story of Sue Parker, who had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal motor neurone disease. At 75, Parker looked relatively well but had less than a year to live.

A registered nurse, Parker knew what the disease would take from her in the last stages, and she wasn’t having it. She circled her self-described “use-by date” in the calendar with a heart, gathered her family in the garden – and chased down her medication with a shot of whisky.

Parker was the first person Kingma met for the book. Before their photoshoot, he writes, “She cheerfully got me drunk”. On the last of her days, she allayed his concerns about whether he was imposing. He writes: “This is going to be a wonderful send off,” she told me. “Of course I want you here.”

But Kingma doesn’t make VAD look like an easy way out. He allows space for conflicting emotions, including fear and doubt. Even advocate Denton, in an introductory essay, admits to shock when a close friend accessed the laws his own organisation fought for.

After gaining medical approval for assisted dying – which has strict eligibility criteria – not all of Kingma’s subjects followed through. Sometimes, death came for them earlier than expected, or their illness robbed them of decision-making capacity.

But a common theme that emerges is the comfort Kingma’s subjects draw from having agency over their own departure. “I don’t want to die, but it’s so important to me to know that I can call the shots,” said Barry Walton, who had bowel cancer.

Kingma also spent time with health professionals who helped guide his subjects on their way, including general practitioners, anaesthetists, social workers and pharmacists. The work is rewarding, but naturally takes a toll, especially on those asked to administer life-ending medication.

“It takes a lot to do that and for it not to affect you,” Kingma says. “I think they probably felt responsible to a certain degree that they had ended this person’s life, and how can that not sit heavily? It has to.”

Naturally, the project deeply affected Kingma, too. Inevitably, he formed attachments to the people he met. Some, like Nigel Taimanu, became friends. Kingma recalls Nigel “hugging me tightly and refusing to let me go on the last day of his life, concerned about my tears”. He writes of how Nigel consoled the photographer, telling him: “I’ve chosen this, please don’t feel sorry for me.”

“You build relationships, and that’s the tricky part, because you get to know these people,” Kingma said. “It’s incredibly difficult to do that and not feel responsible.”

There is a shortage of medical practitioners willing to aid terminally ill people in their wishes to end their suffering. Some are guided by deep ethical, moral and religious objections; many more feel unable to bear the psychological burden involved.

Assisted dying is now legal in all Australian states and territories – except, ironically, the NT, which became the first jurisdiction in Australia to pass legislation in 1995 before the Howard government overturned the laws.

New South Wales was the last state to legalise VAD in November 2023, while laws will go into effect in the ACT this November.

For Kingma, putting together The Power of Choice helped demystify, not just assisted dying, but death itself. What stays with him is the courage of the people who allowed him into their lives, sometimes in their last moments.

“Why would they do that?” he asks himself. “I’ve often said, if I had a photographer come to my door, would I do that? And I don’t know. I want to say yes. But I think it would have been a no.”

-

The Power of Choice by Julian Kingma with Steve Offner is out now through NewSouth Books

.png) 22 hours ago

5

22 hours ago

5