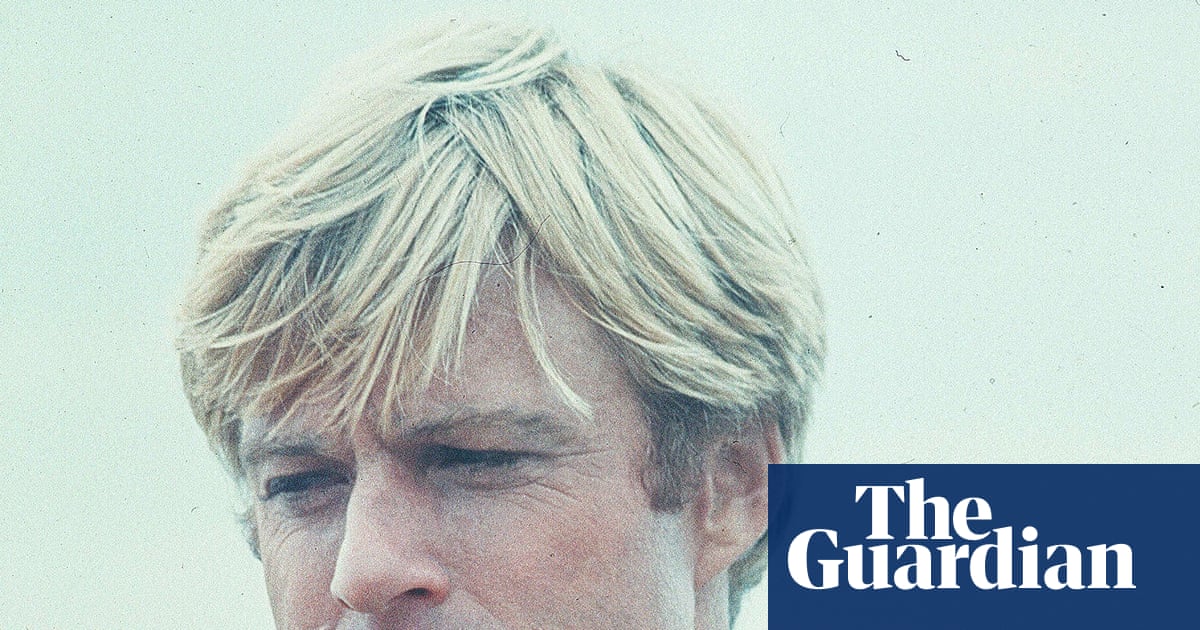

As a former football pundit, columnist, seminarian and novelist, André Ventura is not a man given to understatement. But as the final results of Portugal’s snap general election confirmed that his far-right Chega party had leapfrogged the socialists to become the second biggest party in parliament, his words may have been spot on.

“Nothing will be the same again,” the newly minted leader of the opposition promised after Wednesday’s tally. Ventura also told the Portuguese people that Chega would not be seeking to emulate the centre-left Socialist party (PS) or the centre-right Social Democratic party (PSD) which have, between them, governed the country since its return to democracy after the Salazar dictatorship.

“Don’t expect from Chega what the PS and PSD did for 50 years,” he said. “That’s why people now want a different party.”

That much seems certain. Although the Democratic Alliance, led by Luís Montenegro of the PSD, finished first and increased its share of the vote, it once again fell well short of a majority. The PS, meanwhile, suffered such a humiliating collapse that its leader, Pedro Nuno Santos, announced his resignation even before the final results were in.

Chega’s triumphant performance offers conclusive proof that the era of Portuguese exceptionalism – the notion that the country’s still-recent experience of dictatorship had immunised it against the far right – has come to an end. As in so many countries across Europe, social democratic parties are in retreat while strident populists have made once-unlikely breakthroughs.

Chega’s populist policies – which include stricter controls on migration and chemical castration for paedophiles – have certainly grabbed voters’ attention, as has Ventura’s demonisation of Portugal’s Roma population.

But how has the party, which Ventura founded just six years ago, managed to travel so far, so fast?

“Chega’s success has to be understood in the context of the Portuguese electorate’s attitudes over the past decade,” said Marina Costa Lobo, a professor at the University of Lisbon’s Institute of Social Sciences.

“We’ve had a great deal of abstention – which was hiding a lot of dissatisfaction with the political system and a lot of frustration with the political elite – and fairly widespread populist attitudes.”

All that was missing, she added, was the right party – and the right leader – to capitalise on that dissatisfaction: “In 2019, André Ventura got elected to parliament and he’s a very able leader in terms of articulating these grievances.”

Costa Lobo said the PSD and the PS also bore some responsibility for Chega’s rapid rise because of the number of elections the country had endured over the past few years – three snap general elections in three years. Rather than sensing that the weary and disillusioned national mood meant that more elections would only favour Chega’s growth, the mainstream parties “dropped the ball” and chose instead to focus on their own political squabbles.

She added that Portugal’s previous status as an outlier when it came to the rise of the European far right should have given the PSD and the PS pause for thought before they handed Chega repeated opportunities for electoral growth.

after newsletter promotion

Both Costa Lobo and Vicente Valentim, a professor of political science at IE University, also point to the role that the media has played in all this.

“The media gave Ventura a lot of attention,” said Valentim. “It’s been reported that between 2022 and 2024, he got more than double the number of interviews that Luís Montenegro, the leader of the PSD, did – and he was the prime minister. The amount of media coverage he got was completely through the roof.”

After initially refusing to touch the unpalatable issues that Ventura would go on to make his political staples, said Costa Lobo, the media had belatedly realised that “that kind of speech gets a lot of clicks and audiences … and they have also contributed, as a multiplier effect, to his success and his ability to reach the electorate”.

Valentim said while the Portuguese socialists were struggling with the same issues as their colleagues in other centre-left European parties, they also had to contend with a leader who never became as popular as the party hoped – and an ageing support base. What’s more, having been in government from 2015 to 2024, the PS was ill-equipped to push itself as a fresh alternative to Montenegro’s administration.

“The long-term story is that centre-left parties across Europe are losing many votes – it’s not just the case in Portugal,” he said. “In Portugal, the socialists have the oldest electorate of the main parties, so they do have an issue that their electorate is quite literally dying out and they’ve had a hard time capitalising on younger voters, which is where the far right is doing well.”

The question now is whether Chega has peaked – or whether a spell in opposition will help them grow even more.

“I think Chega are in the best position they could be right now to keep growing because they’re the opposition party,” said Valentim, “which is where these parties are typically better because they’re much better at finding problems than finding solutions.”

.png) 3 months ago

85

3 months ago

85