A quarter of Okinawan civilians died – many after being told to kill themselves, or from starvation. But the hunt for their remains is being complicated by some modern-day inhabitants: tens of thousands of US soldiers

Part 1

The Bone Hunter

Today, the tranquility of this road dissecting the Okinawan jungle is broken only by occasional passing cars and wind rustling through the foliage. For centuries it was a well-worn bridleway in the town of Itoman, on the island’s south-west coast. But 80 years ago, the clip of hooves gave way to the crackle of gunfire, when this sub-tropical Japanese island 1,000 miles south of Tokyo became the scene of the bloodiest battle of the Pacific war.

When the fighting ended three months later, 200,000 Japanese and Americans were dead, including an estimated 90,000 civilians – around a quarter of Okinawa’s non-military population. Many died during the US invasion or from starvation; others killed themselves in groups on the orders of the Japanese military, huddling in caves before detonating grenades – an irreversible flight from the terror of the “typhoon of steel” raging outside.

Takamatsu Gushiken wonders if something similar happened to the owner of a bone fragment he has uncovered deep inside one of the caves, known locally as gama, that dot Okinawa’s southern reaches. In some, Japanese soldiers laid in wait for the advancing Americans; in others, families – usually women and children – prayed for the guns to fall silent.

“I think it’s from the hand of a young boy or girl,” says Gushiken, a 71-year-old volunteer “bone hunter” who has spent decades scraping away at the hardened crust of Okinawa’s cave floors in search of remains that would otherwise stay buried where their owners died. “But it is impossible to say if they were killed or committed suicide.”

When the battle ended, the corpses of civilians and men in uniform were scattered over the fields. For the survivors, their island now under US military occupation just weeks before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, life could only restart once they had attended to the dead.

“The first thing they did was collect the corpses,” Gushiken explains. “There were lots of dead bodies, on the roads, in villages, even in the back yards of their own homes.”

Watch the film 10:41

The Bone Hunter Unearthing the horror of war in Okinawa This Guardian documentary follows peace activist Takamatsu Gushiken, 71, searches for the remains of people who were killed during the Battle of Okinawa, one of the bloodiest chapters in the second world war. As the US seeks to bolster its military presence on the island, due to its close proximity to China, Taiwan and North Korea, we explore the multi-layered tensions that have haunted the people of Okinawa for 80 years

- Director and Cinematographer: David Levene

- Editor and Executive Producer: Laurence Topham

- Guardian Reporter: Justin McCurry

- Music: Christoffer Moe Ditlevsen

- Graphic Design: Harry Fischer

- Animation: Joseph Pierce

- Location Fixers: Naoko Uchima, Chris Willson

- Production Coordinator: Suzy Hall

- Commissioning Editor, Guardian Australia: Bonnie Malkin

- Head of Documentaries, The Guardian: Lindsay Poulton

Some of the remains have been committed to the earth in perpetuity, buried beneath postwar housing complexes, businesses and other infrastructure, turning Okinawa’s killing fields into countless unmarked graves.

As the island prepares to mark 80 years since the end of the battle on 23 June, Gushiken refuses to abandon his mission to uncover as many remains as possible, identify them and return them to their families.

Most of the remains of the estimated 188,140 Japanese killed in the battle have been collected and placed in the national cemetery on the island, according to the health ministry. But the government’s DNA matching efforts have been painfully slow and inadequate.

“It’s been 80 years, so it’s very difficult to find remains … but they are still there,” says Gushiken, who recalls finding skulls encased in military helmets during childhood insect hunts in the mountains. “And the bones are getting smaller and smaller.”

The passage of time, and the chaotic circumstances surrounding the victims’ deaths, mean only a few families will gain any sense of closure. The remains of about 1,400 people found on Okinawa – including hundreds uncovered by Gushiken and other volunteers – sit in storage for possible identification with DNA testing. But so far just six have been identified and returned to their families.

Gushiken is motivated by more than a sense of duty towards the dead of Okinawa – military and civilian, Japanese and American, and, according to estimates, more than 3,500 Koreans who were forced to fight for Imperial Japan, then their country’s colonial ruler.

Standing at the edge of a field, he watches diggers remove white, coral-laced soil from a distant quarry. Here and in other locations, he says, Japan’s government, with the support of the US, is engaging in an act of desecration against the unknown number of war dead whose remains have yet to be found, by using the soil where they fell as landfill for the use of a new generation of American soldiers.

“Instead, this should be a place where people can go and learn about how people died here,” Gushiken says. “Where they can think about the meaning of war and peace, and pray for the dead.”

Part 2

One island, two worlds

On 1 April 1945, US troops landed on Okinawa during their push towards mainland Japan, beginning a battle that lasted until late June. About 12,000 Americans and more than 188,000 Japanese died.

Hatsue Fukumine recalls seeing US planes fly towards her home on Tarama, a dot in the ocean west of the main Okinawan island. “My mother was deaf and so couldn’t hear the planes,” says Fukumine. “I used to run over to her, gesture and grab her hand as we ran to the air raid shelters.”

Tarama, home to a small Japanese garrison, was targeted by air raids and naval bombardment. “There was practically nothing to bomb there,” says Fukumine, who moved to the main island in her teens to work in a pineapple canning factory. She gained her high school graduation certificate at 70 and, now 90, has spent the past decade hosting a weekly community radio show.

By the time Fukumine had married and had three children, Okinawa was under US occupation, and would remain effectively ruled from Washington until 1972, two decades longer than the rest of Japan.

But the US occupation did not end with Okinawa’s return to Japanese control. Today it is a fortress, as host to more than half of the 47,000 US troops in Japan and about three-quarters of its military bases.

Postwar geopolitics thrust the site of the last major battle of the Pacific war into its central role in present-day tensions, amid Chinese claims over disputed parts of the East and South China Seas, and the emergence of a nuclear-armed North Korea. And it is here, in the cobalt-blue seas of Japan’s southernmost prefecture, that the US response to any emergency in the Taiwan strait will begin.

While Okinawa’s economic, educational and social development lagged behind the rest of Japan, huge swathes of land were taken over by the US military, as the island became a crucial support base – an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” – during the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Today, the island occupies an uneasy place in the Japanese consciousness: holidaymakers flock there in search of sun and immersion in a culture that bears little resemblance to that of the mainland. For all its exotic attraction, this island of 1.4 million has higher levels of unemployment and poverty than anywhere else in Japan. It is a living study in cultural contrasts, from the ubiquitous tattoo parlours and bars catering to servicemen along Gate Street near Kadena, the biggest US air base in east Asia, to quiet villages whose architecture speaks to Okinawa’s time as an independent kingdom, with close trading and cultural ties to China and south-east Asia until it was annexed by Japan in the late 19th century.

The eight decades since the battle of Okinawa are also the story of two communities forced to live in proximity, sometimes with success, but often against a backdrop of resentment and suspicion.

Those sentiments are at their most visceral in Ginowan, a densely populated city dominated by Futenma, a sprawling marine corps air base whose perimeter is all that divides its helicopters and tilt-rotor Osprey planes from schools, hospitals and homes.

After the 1995 abduction and rape of a 12-year-old girl by three US servicemen, Tokyo and Washington agreed to reduce the US military footprint on Okinawa by closing Futenma and relocating its functions to a more remote location on the island’s north-east coast. In addition, 9,000 US marines would be sent to Guam, Hawaii and other US territories.

Construction of the new base, in the fishing village of Henoko, has been delayed by local opposition and a string of legal challenges. On a recent afternoon, barges dumped rubble into the bay – the foundations for an offshore runway – while a Japanese coast guard vessel played cat-and-mouse with protesters in canoes who had breached the site’s floating barrier.

The Henoko base is opposed by most islanders, who say it will destroy the marine environment – including one of the few remaining habitats of the dugong – and do little to reduce the US military footprint. It is not expected to be completed until at least 2036 – 40 years after Japan and the US agreed to build it.

Political controversy aside, Gushiken believes the base represents a moral affront targeting Okinawa’s war dead and their families: some of the soil and sediment being used to reclaim land in the bay comes from seven former sites of Pacific war battles, where the remains of fallen soldiers and civilians remain buried.

Dumping those remains into the sea to build a base for the US troops is, he says, “a betrayal to their comrades-in-arms, to bereaved families and to the people of Japan”.

Part 3

Tragedy at sea

The battle of Okinawa had become an inevitability a year before American troops came ashore, when the US capture of the Pacific island of Saipan signalled an invasion was only a matter of time.

In July 1944, the government, anticipating an American assault on Okinawa, ordered the evacuation of 100,000 older people, women and children to Japan’s main islands and Taiwan.

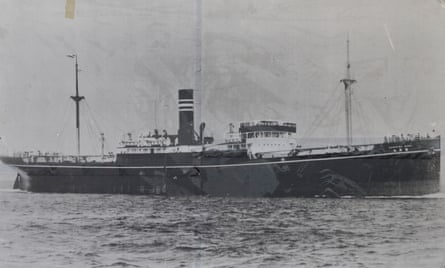

On 21 August 1944, Hisashi Teruya boarded the Tsushima Maru, a transport vessel, at Naha port along with his mother, Shige, and his elder sister, Mitsuko. His father had been conscripted to fight in Siberia.

The following evening their ship was struck by a US torpedo, killing 1,484 of the 1,800 passengers, including 784 schoolchildren.

Teruya was asleep when the torpedo struck. “I was four years old at the time, so I don’t remember much,” he says. He has flashbacks of climbing a ladder up to the deck, which was swarming with petrified passengers. They were told to jump into the sea before the badly damaged ship sank, dragging them down with it. “My mother pulled me by the hand, and we jumped.” Moments later, as they clung to the ropes of a large soy sauce barrel, Teruya’s mother instructed him to hold on while she searched for his sister.

That was the last time he saw his mother, who died along with his sister. As an approaching typhoon kicked up waves, Teruya drifted for 16 hours before being rescued by a fishing boat. “I was just a little boy, so I can’t remember my mother’s face … only from photos,” he says. “And I don’t remember playing with my sister. I don’t have any of those normal memories.”

Teruya, who spent his childhood being passed around by relatives, did not utter a word about the Tsushima Maru tragedy until he was in his early 70s. “I was getting old, so I thought it was time to open up about it,” he says in an interview at a memorial museum devoted to the tragedy.

The 85-year-old’s visits to the museum begin with a greeting before the grainy black-and-white photos of Shige and Mitsuko, exhibited on walls alongside images of hundreds of other victims. “I tell them I have come to talk about the Tsushima Maru,” he says. With no family graves to visit, he set up a makeshift altar, his father – who did not survive the war – mother and sister each represented by stones he had found at personally meaningful locations.

“It won’t be long until all of the people who lived through the war have gone, so I’m afraid that people will forget what happened,” he says. “I hope that people who come here and learn about the Tsushima Maru will understand the horrors of war and realise that it can never happen again.”

At 95, Eiki Senaha has clearer memories of the months his home turned into a battlefield. Then in his teens, he, like other Japanese schoolchildren, had been forced to abandon his studies to help the war effort.

“We were mobilised daily to build Kadena airfield,” says Senaha, a celebrated academic who is now president of Meio University. “We carried shovels of dirt from morning till night. In those days, there was no asphalt or cement, so we had to break up rocks to build the runway.”

In late March 1945, with the US invasion imminent, Senaha and other students were given a week to spend with their parents before returning to wartime duty. They were advised that this would be a good time to “say goodbye”.

But the air raids quickly intensified, forcing Senaha and his family to spend weeks hiding in the mountains. “I could hear the sound of artillery shells,” he says. “When they landed, they exploded and shrapnel would fly everywhere, slicing the branches off trees. I didn’t want to move. My grandmother, who had poor eyesight, never stopped shaking.”

Senaha had been told by military officials assigned to his school to kill himself rather than be captured and tortured by American soldiers. But as fires raged around his family’s hideout, he and his relatives emerged with their arms raised to be confronted by dogs and soldiers with guns. “I had decided to come out rather than die,” he said. “I wanted to save my own life.”

After a month in a makeshift camp as civilian prisoners, Senaha and his family were allowed to return to their village. It was a miracle that he had survived. “My classmates died in droves. I’m sorry that they died and that I’m still alive. What did they think they were dying for? They died for their families. Not for the emperor. They died for their families, for the people of Okinawa.”

Part 4

Laying ghosts to rest

As darkness falls, Gushiken returns on his moped to a hut outside his home and switches on his desk lamp. He leafs through an illustrated medical dictionary, his focus shifting between its pages to the fragments of bones on his desk.

“When I see the state of the bones, like those that were turned to charcoal by flamethrowers, I feel very sad,” he says. “Especially if they belong to children.”

On 23 June, the people of Okinawa will gather at the Cornerstone of Peace to mark the day their war ended, less than two months before Japan’s disastrous militarist adventures were halted by two nuclear explosions hundreds of miles away.

The anniversary will be a chance for Gushiken to reflect on how much – and how little – has changed in the eight decades since Japan embraced constitutional democracy, and his island became an American military fortress.

“Back then, if people spoke out against the war they were immediately arrested by the military police. There was no such thing as freedom of speech. That’s why it’s important that we speak out now, that we don’t have to do as the government tells us. That we decide which direction the country goes in.”

For now, though, Okinawa’s future appears to be out of the hands of Gushiken and the majority of residents who oppose the new base in Henoko. Japan’s government ignored the overwhelming “no” vote delivered in a non-binding referendum in 2019, and the transfer of thousands of Marines, first agreed in 2012, only began this February, when just 105 left for Guam.

US-Japan ties, and the regional tensions underpinning their alliance, have transformed since the bodies of soldiers and civilians were committed to Okinawa’s soil. All the more reason, Gushiken says, for both countries to lay the ghosts of the past to rest.

“By using the soil to build the base, the Japanese government is stamping on the dignity of people who died in the battle – not just Japanese, but Americans and other people too,” he says. “It’s as if they are being killed all over again.”

-

About this article

-

Writer – Justin McCurry

-

Video and photography - David Levene

-

Multimedia editor – Laurence Topham

-

Lead Designer - Harry Fischer

-

Interactive Developers – Alessia Amitrano and Pip Lev

-

Commissioning editor – Bonnie Malkin

.png) 3 months ago

85

3 months ago

85