To date, the American photographer Peter Hujar’s most well-known shot is his beautiful and melancholy portrait of Warhol “superstar” Candy Darling in repose on her deathbed. She is surrounded by flowers, a single rose lying by her side. Made in 1973 at her request, it is an artfully staged collaboration with, as Hujar later put it, “Candy playing every death scene in every movie”. A superstar, then, to the last.

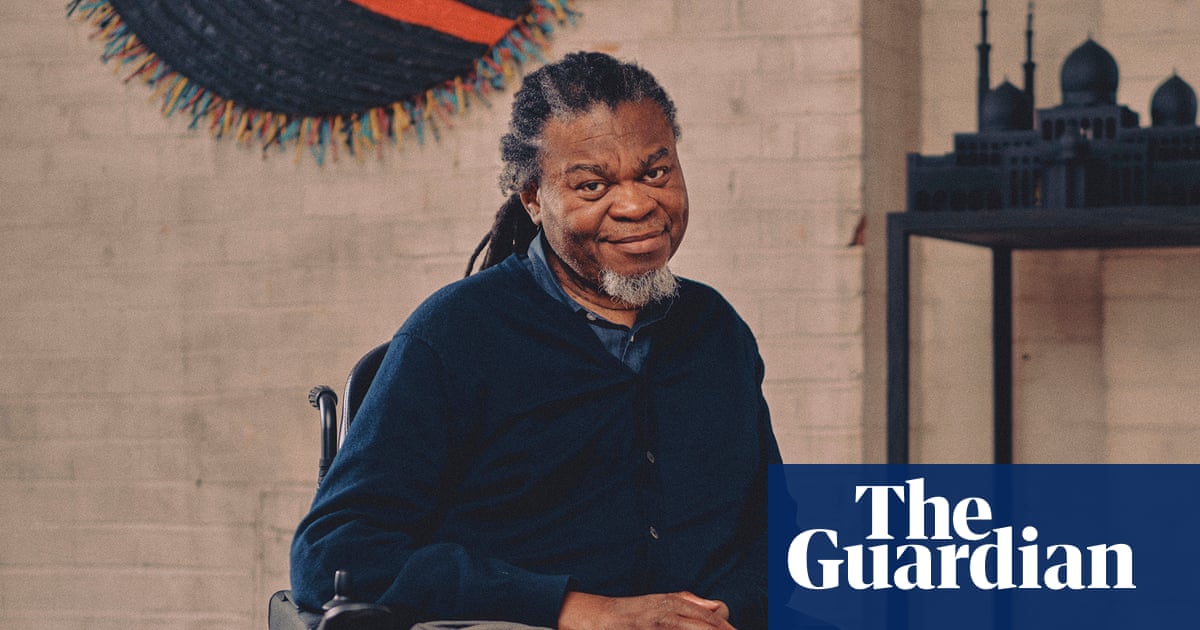

The image is an intriguing one in the long arc of Hujar’s posthumous recognition, having brought him to the attention of a new, younger audience in 2005 when it featured on the cover of I Am a Bird Now, the debut album of Antony and the Johnsons. In its elaborate choreography, though, the Darling portrait is not really indicative of the impressive depth and breadth of Hujar’s work, which is on full display in Eyes Open in the Dark, an intriguing exhibition by the artist’s friend and printer, Gary Schneider, and his biographer, John Douglas Miller, at east London’s Raven Row gallery.

There, a different but related portrait of Candy Darling from 1972 moves in closer to its subject, whose beauty and melancholy are more starkly evoked, her body enfolded in white linen on which you can just make out the embossed name of the Cabrini medical centre. She is one of many ghosts that haunt this exhibition, their monochrome portraits a testimony to Hujar’s singular style: a seamless merging of somewhat unconventional technical skill – his odd eye for composition – and an ability to evoke a sense of deep intimacy, either real or constructed, between himself and his subjects.

The late Peter Schjedahl, writing in the New Yorker, noted that Hujar, who died from Aids-related pneumonia, aged 53, in 1987, made some of his best work at the “historic crossroads of high art and lowlife” that was downtown New York in the 1970s. Many of the portraits here reflect that heady era of creative experimentation, whether of the famous – Susan Sontag, William Burroughs, John Waters, Fran Lebowitz – or the less well known, which include many of Hujar’s friends and acquaintances from the New York gay scene of the time. The latter range in tone from the tender – several studies of his lover, the American artist and gay activist David Wojnarowicz – to the provocatively graphic: a nude portrait of dancer Bruce de Sainte Croix, seated, eyes downcast to where his right hand grasps his erect penis.

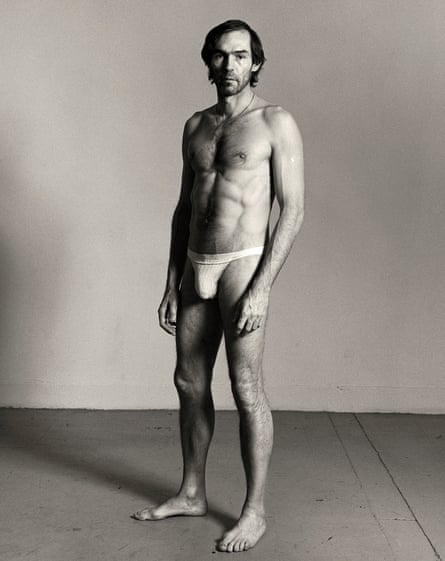

Hujar’s self-portraits tend towards the more straightforward or archly mischievous, but on one occasion, be warned, he approaches the more hardcore homoerotic terrain that Robert Mapplethorpe explored with such joltingly uncompromising results. At other times, his formative influences, such as Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, are more detectable, as with two portraits of his close friend, the independent film-maker and actor John Heys, whose striking profile is bathed in shadows and soft light.

Hujar also photographed animals with quiet attentiveness, including a friend’s dog, looking poised and alert, several stately horses and, most mysteriously, a pensive cow peering though barbed wire, which he once referred to as a self-portrait.

Outside his studio, he made work that ranged further and wider, from street photographs of the gay community at their various gathering spots on Manhattan’s West Side piers to architectural images of the city’s skyline. In his formative years, Hujar studied film at Rome’s Cinecittà studios, and there is something cinematic in his noirishly atmospheric nocturnal shots of deserted New York neighbourhoods. That these liminal locations were gay cruising spots adds a crucial subtext that is personal and, as the years pass, historically and culturally significant.

The Hudson river appears in a painterly series of tightly cropped closeups of its lapping waves, one of which was originally included in a grid of photographs that were exhibited posthumously as part of an important group show, Witness: Against our Vanishing, staged in New York in 1989. It reflected the dramatic toll that HIV/Aids had taken on the downtown artistic scene and, in that context, the almost meditative quality of the rippling water perhaps offered a moment of quiet, almost holy, contemplation. They remain at once surprising and calming.

It’s the human portraits that linger though, many of them featuring his subjects reclining. A nude from 1975, mysteriously titled TC, exudes a languorous sensuality redolent of a classical painting. In another, the downtown scenester Cookie Mueller, also immortalised by Nan Goldin, stares out at us almost defiantly. In stark contrast, an unknown girl sleeping on the tiled floor of a New York doorway looks comatose. That this snatched portrait somehow evades intrusiveness is testament to Hujar’s complex gaze.

Elsewhere, his male subjects often contort their naked bodies at his instruction. A young Schneider bends away from the camera, one leg pulled up and over his bowed head. Another acquaintance, Daniel Schock, leans forward on his chair to suck his big toe. The results are too angular and uneasy to be either sensual or artful, instead falling somewhere in between.

Then there are the dead and dying. In an essay for Portraits in Life and Death, the only book of photographs published by Hujar in his lifetime, Sontag proclaimed somewhat overdramatically that photography “converts the whole world into a cemetery”. That is not quite the case here – or indeed anywhere – but she herself is now, of course, among the departed whose portraits punctuate this exhibition. Likewise the artist Paul Thek, who was Hujar’s partner in the early 1960s when the pair travelled together to Italy. Thek died from Aids a year after Hujar, in 1988. Sontag’s book Aids and its Metaphors, published in 1989, is dedicated to him.

Wojnarowicz also died of Aids in 1992. The most austerely haunting images in this exhibition belong to him rather than Hujar. They comprise a triptych of the dying Hujar that is both unflinching and almost holy in the manner of a modern day pietà: the photographer’s gaunt bearded face, his right hand seeming to grasp a sheet, his pale feet protruding from the bed covers. Wojnarowicz made them in room 1423 of the Cabrini centre, the same room in which Hujar had created his famous Candy Darling on Her Deathbed 14 years earlier.

Eyes Open in the Dark is a show full of strange echoes and traces of creative paths once crossed. It reaffirms the beautiful and melancholy genius of Hujar, a towering 20th-century artist whose time has finally come.

.png) 2 months ago

24

2 months ago

24