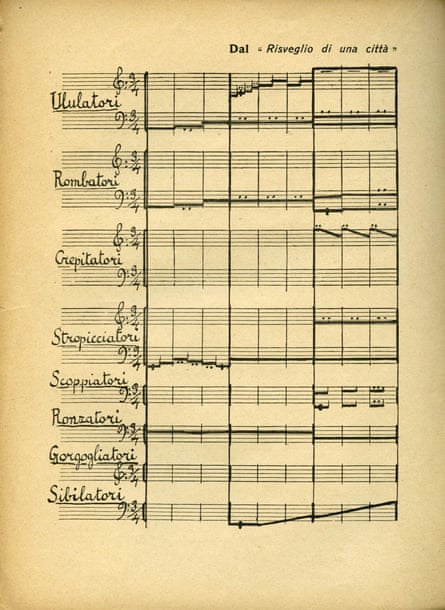

Today it is the venerable home of the English National Opera, but back in June 1914, the London Coliseum welcomed an act quite unlike anything seen there before or since: an orchestra of futurist noise machines. With their aggressively boxy chassis and funnel-like hooters, they resembled a flock of cubist birds or an artillery battery designed by Tove Jansson. Even stranger were the sounds they made. Each one had its own onomatopoeic name and in combination they evoked more a diagnostic toolkit for gastroenterologists than a set of musical instruments: there was the rumbler (or rombatore), the gurgler (gorgogliatore), and, most disturbingly of all, the howler (ululatore). It was a pretty far cry from The Pirates of Penzance.

All things considered, the response of the London audience 110 years ago was only to be expected. An instrument called the scoppiatore (or “burster”), supposed to imitate the sound of a combustion engine, prompted cries of “Change ’ere for Peckham!” The gorgogliatore prompted one wag in the stalls to cry out, “Take the baby home, can’t you?” But today those machines are widely recognised as the opening towards an entirely new conception of what music can be. Genres like sound art, noise music, musique concrète, and industrial techno all trace their origins back to that motley assortment of rumbling, gurgling, howling boxes. The original instruments are now long lost, probably destroyed during the second world war. But an ambitious project to rebuild the futurist instrumentarium will see their replicas return to the London stage this week in a concert featuring new works specially composed for them by Pauline Oliveros, Peter Ablinger, Tony Conrad, and others.

The original devices were the work of an Italian painter named Luigi Russolo and his assistant, Ugo Piatti, members of the Italian futurist group founded five years earlier. Collectively, they called them intonarumori: “noise intoners”. They were intended to “tune” the rising clamour of industrial society, investing it with newfound poetry. The futurists had pledged to “destroy the museums” and “sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards”. Katia Pizzi, author of the book Italian Futurism and the Machine, told me that Russolo’s intonarumori “embody the aural landscape and the fast tempo of the machine age”.

Just over a year before the London concert, Russolo had announced his intentions in a febrile manifesto called The Art of Noises. “Musical sound is too limited,” he declared. “We must break out of this limited circle of sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.” These days it is perfectly common for records to contain samples of car horns, gun shots and cash registers, but decades before the first works composed using real-world noises, Russolo, just 28 at the time, could already imagine a music made of “the bustle of pistons, the shrieks of power saws, the starting of a streetcar on the tracks”.

He closed his manifesto with the promise of a “new orchestra” capable of realising this “infinite variety”. Amazingly, within just five months, he had built it and was ready for a demonstration at the Milan headquarters of Italian futurism, known as the Casa Rossa, home to the movement’s walrus-like leader, FT Marinetti. One anonymous journalist from the Pall Mall Gazette, present at the time, compared the experience to a “dream”.

The extraordinary speed with which Russolo built his new instruments was almost matched by the project to recreate them. Born in Sardinia, Luciano Chessa moved to California in the 1990s to study music history, soon finding himself surrounded by a vibrant community of experimental instrument builders.

In San Francisco, Bart Hopkin had been publishing the Experimental Musical Instruments journal for 15 years. Since the early 80s, Ellen Fullman, in nearby Berkeley, had been developing her Long String Instrument, drawing long quavering drones from metallic threads more than 20 metres long. Both became friends and collaborators.

Already composing some pretty raucous music of his own, he switched his PhD topic from 16th-century French counterpoint to align more closely with his artistic practice. Russolo, an artist he had been intrigued by ever since seeing a brief seven-bar fragment of his only surviving musical score while still a child, proved the perfect choice. When the curators of New York’s Performa Biennial contacted Chessa in 2008 with a commission to rebuild the futurist’s intonarumori orchestra, he did not hesitate. But he did have a few questions.

Chessa’s project was not the first to attempt a reconstruction of Russolo’s instruments. Several intonarumori were built by musicologist Piero Verardo for the Venice Biennale in 1977. Recordings of them being demonstrated were released on cult Italian label Cramps in the early 80s and the machines themselves later appeared in several exhibitions. But Chessa was clear from the beginning of the project that he wasn’t going to “build something for museums”. If he was going to build one, he would build the whole set. “Russolo thought of his intonarumori as an organism,” he decided. “Building just one would be like building a car with one wheel.”

He would use robust, practical materials that could be taken on tour. And since an instrument lives or dies by its repertoire, he wanted sufficient budget to commission new works for the orchestra. With these two conditions agreed, he set to work: studying old photographs, sawing wood, vulcanising drum skins. By October 2009, they were ready for their first concert.

Fullman became one of the first composers invited to write for the new orchestra. She described her work for the intonarumori as a “meditation on decayed industrial zones” based on a painting her father, a commercial artist, had made in the late 1930s of an “inactive rural industrial scene”. It’s a work full of gritty texture and restless movement punctuated by sudden breaks and eerie tremors. Listening to it feels rather like being trapped inside a haunted combine harvester. “There is a charge left from the machinery and productivity of the past,” Fullman says, “that energises current usage.” It’s a thrilling piece of music, but it bears the irony that the industrial machines which once fired up the Italian futurists now come twinged with nostalgia for a bygone past.

As a painter, Pizzi told me: “Russolo’s legacy is negligible.” But the part he played in the history of music “is truly profound”. Roberta Cremoncini, director of London’s Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, agrees. Other futurist painters “made more significant contributions” to the field of visual arts, she told me. But Russolo’s interest in “bringing the city into the concert hall”, she said, “was revolutionary – and that’s the real point”. Now Chessa’s reconstructions of Russolos noisy machines open that revolutionary spirit to a new generation of composers and audiences – in all their howling, gurgling, rumbling glory.

.png) 3 months ago

36

3 months ago

36