If you ask art dealers and auctioneers about the legacy of the turn-of-the-century sculptor Medardo Rosso, you are likely to be met with a uniform reply: “Medardo who?” There’s no judgment here. I’ve worked in and around the art world for 20 years, and until recently I hadn’t heard of Rosso either.

In artists’ ateliers, however, Rosso has long been a familiar and revered name. Auguste Rodin, the father of modern sculpture, was his champion and friend until the pair’s fallout. Émile Zola was a fan. The playwright Edward Albee owned a version of his sculpture Enfant Juif; French poet Guillaume Apollinaire described him as “without a doubt the greatest living sculptor”.

Rosso, a new retrospective at Kunstmuseum Basel, contends he brought sculpture into the modern era with busts and figures that seemed to materialise organically out of his materials – wax, plaster, bronze – like spectres in motion. The Swiss art institution has had no trouble finding 60 contemporary artists who feel a kinship with his sculptures, photographs and drawings, his fleeting impressions of street scenes, cafes and clouds – from Louise Bourgeois’s textile sculptures that look like entrails to Francesca Woodman’s wraithlike photographs.

“If you sit 10 gallerists and collectors around a table, nine out of the 10 will not know who Medardo Rosso is,” says Elena Filipovic, the director of Kunstmuseum Basel, which is holding a retrospective on this shadowy figure. “If you sit 10 artists around the table, nine out of the 10 will fall to the floor with excitement.”

There are good reasons why Rosso has fallen into relative obscurity. Some, albeit unintentionally, are Rosso’s fault. For instance, his practice was neurotically self-contained. While Rodin followed the template for becoming famous, Rosso followed his own instincts. Rodin knew to create monumental works – “size matters,” says Filipovic – and that professional marketing was key. Rosso created small-scale works, works seen in the studio, home and exhibitions but not out on the boulevards, and he liked to promote them himself.

He worked, repeatedly, on a relatively small number of motifs. One of his most famous works, Ecce Puer (1906), is of a boy’s head shrouded in a sheet; he’s there but not there. Another, Enfant Malade (1893-95), features the inclined head of a sick child, tipping possibly towards death.

We often use the term “in the flesh” when standing in front of a sculpture, but with Rosso the phrase has a particular resonance: his faces, just that little bit smaller than in real life, with dimensions that add to a sense of unease, look as if they might blink their waxy eyelids. His sickly yellow lumps are not pretty. They’re not Degas’s dancers.

Perhaps the most disturbing of all though is Aetas Aurea (1886), a study of his wife, Giuditta, and their son, Francesco, in which the pair look conjoined at their cheeks. They melt into the background. It’s a horror movie prop rather than a loving family portrait. Other figures are drunk, leaning, screaming. His wax sculptures are the colour of nicotine stains.

Born in Turin in 1858, the second son of a railway worker, Rosso opened his first atelier in Milan in 1882 and circulated with members of the artistic group Scapigliatura – translated as “dishevelment” – a Bohemian set of a socialists and anarchists. Living up to the name, Rosso’s studies in the city’s esteemed Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera were cut short when he was expelled for assaulting another student. Three years later, however, he had a wife and son, and was successfully forging a career in Paris, wooing patrons and winning commissions.

Rosso was definitely a “very idiosyncratic personality, very persuasive, powerful, winning, someone with a big heart, especially for children, but also suspicious, controlling, obsessively pursuing his cause,” says Heike Eipeldauer, a curator and Rosso expert at the Mumok museum in Vienna, Austria. There were a lot of disagreements: his wife left him and one of his closest friends cut him off after an argument about debts. And then there was Rodin, who he got into a public spat with over who had influenced whom. “They were friends, until they weren’t,” says Filipovic.

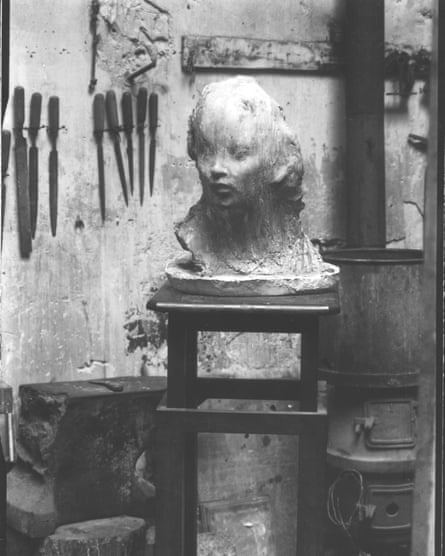

His intractable nature could work against him. He cast his own works – eating into his time and reducing the number of works created – while Rodin used foundries. And Rodin hired Edward Steichen and other well-known photographers to capture his works and produce portraits of him as the great master in the studio (often with a hammer and chisel, even though he never carved marble himself). Rosso’s sculptures were only ever photographed by the artist himself.

“He wanted to control the image,” says Filipovic. “He understood that photography and how you saw the work was also the work.” The exhibition features about 200 of Rosso’s photographs: frail prints of sculptures, some as small as stamps, otherworldly portraits rather than iconic marketing shots. He lit and staged them, with an ethereal aesthetic that echoed the Victorian craze for spirit photography.

While Rosso’s photographic studies reanimate objects, his studio-set self-portraits conjure up a phantom, his scruffy features bleached by the sun through his studio’s skylight, his figure blurred in movement: studies as faint and mercurial as his artistic footprint.

Having spent his last two decades constantly reworking a few subjects, the artist died in 1928, aged 69. He had dropped glass negatives on his foot, resulting first in the amputation of several toes, then part of his leg and finally a fatal case of blood poisoning. A gradual erosion.

Today, Rosso’s complicated nature hampers research, explains his great-granddaughter, Danila Marsure Rosso, who manages the artist’s estate. “He destroyed all the letters he received because he said that nobody should enter in his private life,” she says.

There are no biographies of Rosso. There are dozens of Rodin. Rosso’s auction record stands at £341,000 (for a version of Enfant Juif, sold in London in 2015); Rodin’s record was set in 2016, when the master’s marble Eternal Springtime sold in New York for $20m (£14m). Legacies can pay dividends.

But Rosso’s quirks had their own creative rewards. He invited groups into his studio to watch him sculpt and cast his works, as if he were a performer. “It was about understanding that there is magic in this making,” says Filipovic. “Rodin couldn’t do that because he used a foundry.”

Another idiosyncrasy was Rosso’s fondness for installing sculptures in collectors’ homes in strange, jarring configurations. Context was everything, but not always logical. I can imagine him sitting uncomfortably close to guests at dinner parties just to observe their reaction. Was he a control freak? “Certainly,” says Filipovic. “But don’t you want that in an artist?”

.png) 2 months ago

44

2 months ago

44