Hello and welcome to The Long Wave. Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter tour, which kicked off in California in April, began its European leg in London last week. I went to the first show and considered the legacy-making significance of this latest evolution in the singer’s long career – and the part that left me cold.

A deep dive into the Chitlin’ Circuit

As a native of Houston, Texas, Beyoncé grew up surrounded by cowboy culture. Between 2001 and 2007, she performed four times at the city’s Livestock Show and Rodeo, which was launched in 1931 to promote agriculture through live entertainment and ended up as the largest rodeo in the world. When you consider the depth of southern tradition this generation-defining artist is steeped in, it seems all the more remarkable to be in north London and see people from all corners of the world assembling to become spectators of a rodeo that is all Beyoncé’s own.

Outside Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, there are people in cowboy hats, encrusted with rhinestones or with veils attached; cow-print vests; embroidered boots with spurs; double denim, bandanas, alligator skins and shirts with fringes. Though revellers are greeted with grey skies and a forecast of rain, spirits are high, and their presence summons the sweltering climate of Texas.

I speak to a woman named Marieles, wearing a white and denim cowgirl costume, who has come to London from Panama. It is her second long-haul trip to see Beyoncé – she attended the Renaissance tour in Amsterdam in 2023. Is she as excited by the Cowboy Carter album, Beyoncé’s dive into country music? “I love the impact and the message that it brings,” Marieles tells me. “I feel very empowered as a Black girl with that album. I’d never heard country music before and it taught me a lot about the history.”

The same is true for Cornelius from Germany, who is at his fourth Beyoncé concert. He tells me that on Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé sings with “a lot of love and passion” and that he has become “more open” to country music after listening to it.

A Beyoncé country album had long been predicted. Daddy Lessons (one of my favourites from her 2016 album, Lemonade) was the singer’s first explicit foray into the genre. The track sparked controversy when Beyoncé performed it with the Chicks (then the Dixie Chicks) at the 50th Annual Country Music Association awards (CMAs). Naysayers from the Nashville country music establishment asked why Beyoncé had been invited to perform – her musical background supposedly too R&B and hip-hop, her activism through music the antithesis of the Republican-dominated mainstream country scene. The Chicks, of course, had experienced a formidable backlash in 2003 for expressing shame that George Bush came from their state of Texas.

The lead single from Cowboy Carter, Texas Hold ’Em, was a runaway success, hitting the top spot in 19 countries (including the US and the UK). Significantly, it also reached No 1 on the Hot Country Songs chart in the US, the first record by a Black woman to do so. Unveiling the album’s artwork, Beyoncé suggested that her experience at the CMAs had inspired Cowboy Carter, saying it was “born out of an experience that I had years ago, where I did not feel welcomed … because of that experience I did a deeper dive into the history of country music and studied our rich musical archive”.

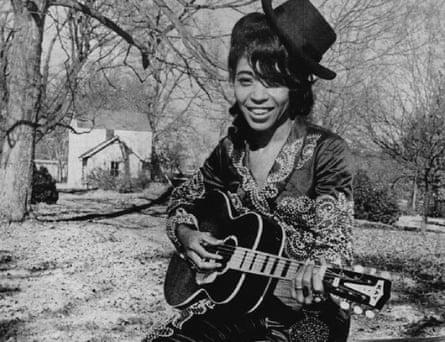

This resulted in Beyoncé inviting Linda Martell, the first Black female singer to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, on to Cowboy Carter as well as including excerpts from Roy Hamilton and Son House on its radio station interludes. This attempt to assert the presence of Black Americans within the history of country music is framed even more vividly on this tour. Its visual storytelling provides an all-singing, all-dancing archive of Black American music that is so alive and dynamic, and which contextualises the voices and instruments you hear.

After all, the secondary title for the Cowboy Carter tour is The Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit, a reference to the performance venues that catered to African American patrons and commercially sustained Black performers in the era of Jim Crow segregation. And God, does this show live up to that entertainment tradition. From her fringed chaps and gloves to her custom Versace-print dresses, Beyoncé looks magnificent, while the stage design is grand and kitschy, with two neon bar signs that say “salon” and “saloon”. At various points, she flies across the stadium on a giant neon horseshoe and a Cadillac, and she rides a gold mechanical bull for a sultry performance of Tyrant.

I first saw Beyoncé on the Formation World Tour when I was 19, and have caught every tour since. This is the most confident and carefree I have seen her – she is visibly having fun. The Cowboy Carter tracks translate so well to the stage, too, with Riiverdance, II Hands II Heaven and Flamenco being particular standouts – on Ya Ya she evokes the ferocious, theatrical rock’n’roll style of Prince and Tina Turner.

All the ancestors are summoned for the Chitlin’ Circuit. On large screens, during performances and interludes, images of Black America’s musical iconography are projected at the audience. There’s a clip of Chuck Berry playing Johnny B Goode at Hullabaloo A Go Go in 1965; a 1932 performance of Cab Calloway and his Cotton Club band’s melancholy hit Minnie the Moocher; Nina Simone singing I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free at Montreux Jazz 1976; Little Richard blazing through Lucille in 1957; Sister Rosetta Tharpe singing The Lonesome Road in 1941 and Berry blasting You Can’t Catch Me in the 1956 film Rock, Rock, Rock!

after newsletter promotion

The references are neverending but they don’t feel like a fleeting history tour. Instead they emphasise how a genre that has been co-opted and framed as “not Black” has a long history of African American pioneers, many of whom forged careers in a segregated US and laid a path for so many others, including Beyoncé.

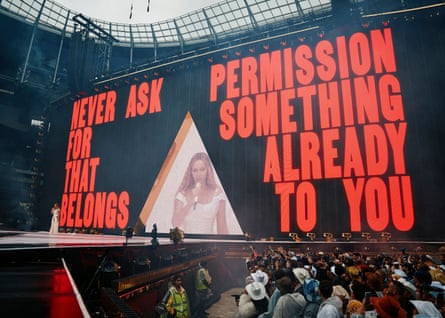

It is interesting to me, though, that after the opening performance of Ameriican Requiem, which, live, has the soulful beauty of a cathedral choir, and her cover of the Beatles’ Blackbird, Beyoncé then sings The Star-Spangled Banner, taking her cue from the incendiary rendition that Jimi Hendrix performed at Woodstock in 1967 in protest against the Vietnam war. The meaning of national symbols such as the anthem, and the American flag projected on the screens before the performance, have a new resonance in the era of Trump 2.0. Can the iconography of such regressive, destructive and supremacist political movements even be redeemed?

Beyoncé clearly believes that it can. On the screen she wears a sash reading “the reclamation of America” – and there is the view that these symbols, like American music, should be strongly reaffirmed as an intrinsic part of Black American identity, especially at a time when Trump is attempting to wash African American history from record. Certainly, I can see that it’s important for Black Americans to express pride in traditions they had a fundamental role in creating. Yet this flag-waving still leaves me cold.

Last year, at Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign rally in Houston, Beyoncé appeared alongside her friend and former Destiny’s Child bandmate Kelly Rowland, describing herself and Rowland as “proud country Texas women”. Harris had been under fire during that campaign for her support of President Joe Biden’s arming of the Israeli state in its onslaught against Gaza. Hendrix’s protest, meanwhile, took place under the Democratic president Lyndon B Johnson, who sent Americans to fight in Vietnam, and drew chants from protesters such as: “Hey, hey, LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?” Americana imagery can’t be neatly divorced from the imperial aspects of the state – and the musicians who Beyoncé admires knew this well.

Even if there are debates still to be had about Beyoncé’s political aesthetics (we have been here since at least her self-titled 2013 visual album), you walk away from Cowboy Carter with no doubt that she is the greatest performer and artist of our time. Some have taken the mood of the tour, the montage of images from Beyoncé’s personal history, and the return of seemingly long-retired tracks including If I Were a Boy and Why Don’t You Love Me as an indication that she is inching towards retirement – but I have never seen a clearer example of a performer who will not be slowed down by naysayers or knee injuries. The rodeo queen rides on.

To receive the complete version of The Long Wave in your inbox every Wednesday, please subscribe here.

.png) 3 months ago

39

3 months ago

39