A man accused of attacking Salman Rushdie as he was being introduced at a literary lecture in New York state in 2022 is going on trial this week in a case likely to create global headlines.

The trial could upend life in the tiny upstate New York village of Mayville, whose population of less than 1,500 is not accustomed to finding itself at the center of a media circus covering the attempted assassination of one of the world’s most famous writers.

Hadi Matar, 26, of New Jersey, is accused of attempted murder and assault in the attack in Chautauqua, allegedly stabbing the author 10 times, in the abdomen and neck. Rushdie later lost sight in one eye and sustained nerve and liver damage.

The trial, which starts on Tuesday with jury selection, was postponed from January 2023, when Matar’s defense team requested the manuscript of Rushdie’s memoir Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, and again in October, after Matar’s defense appealed for a change of venue, arguing that an impartial jury of Matar’s peers could not be found in Chautauqua county.

The author has credited a series of “man-made miracles” for surviving the attack.

“There was a slash right the way across my neck here, but it didn’t seem to cut the artery … there’s three stab wounds down the centre of my torso, but they missed the heart,” he told CBC Radio’s The Current. “That’s what we call good luck.”

After refusing a plea deal for a 20-year sentence, Matar also faces federal terrorism-related charges, including providing “material support and resources” to the Iran-backed Lebanese group Hezbollah.

Prosecutors in the federal case argue that Matar’s attack was not random but motivated by the fatwa, or death threat, issued by Iran’s leadership against Rushdie over the author’s 1988 novel The Satanic Verses, which many Muslims considered to be blasphemous.

Rushdie spent years in hiding after the fatwa was issued in 1989, but began to reemerge in the late 1990s. He has traveled mostly freely over the past two decades and become a fairly frequent fixture on the literary circuit and television shows.

Matar, who was born in the US but holds dual citizenship with Lebanon, has pleaded not guilty to both charges, and has been held without bail at the Chautauqua county jail. His mother has indicated he was radicalized during a trip to see his father in Lebanon in 2018.

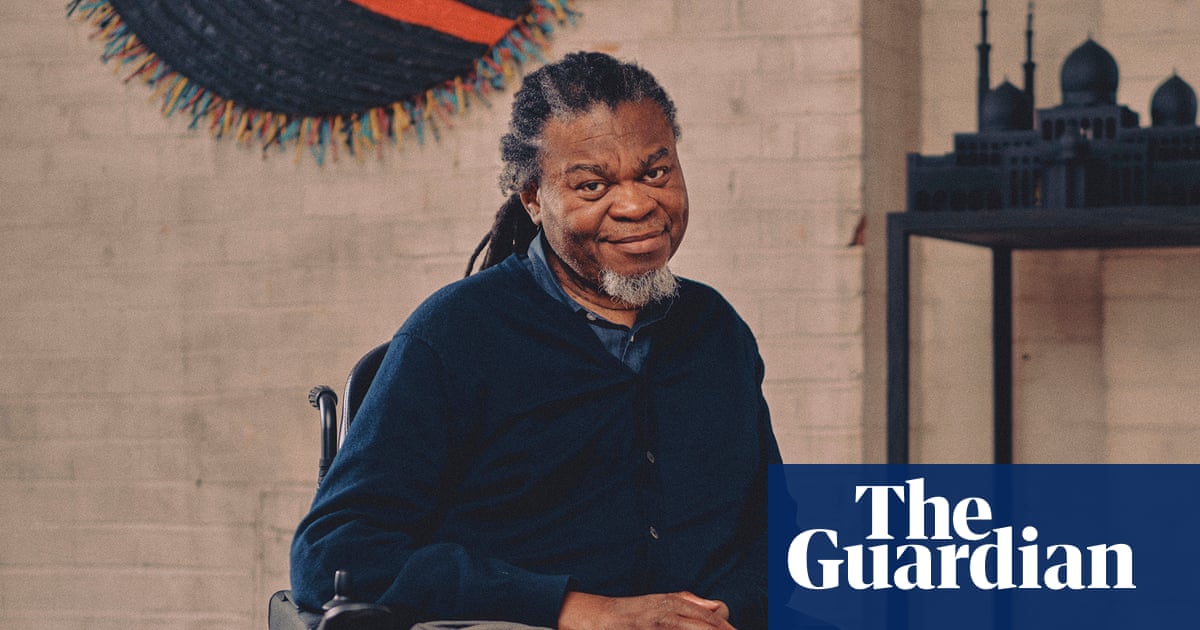

Rushdie, 77, and Henry Reese, who co-founded Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum to grant sanctuary to writers exiled under threat of persecution, and whom Rushdie has credited for helping to save his life, are expected to testify.

But prosecutors in Matar’s trial have said jurors likely will not hear about the fatwa. “We’re not going there,” district attorney Jason Schmidt said during a recent hearing.

Schmidt said presenting a motive was unnecessary since the attack was witnessed and recorded on cellphones by members of the audience.

Schmidt previously told reporters that his “biggest hurdle” would be picking a fair and impartial jury due to the level of publicity surrounding the incident. Matar’s lawyer, Nathan Barone, told the court he fears the current global unrest would influence their feelings toward his client.

“We’re concerned there may be prejudicial feelings in the community,” said Barone, who also has sought a change of venue for the trial. With tensions around religious-motivated violence running high, the judge in the case has ordered both parties to avoid statements to the media.

In an interview with the Rochester Post-Journal, Barone said he has concerns about “inherent and implicit bias” toward Arab Americans and the Muslim or Arab American community in Chautauqua county.

“There’s a segment of the population that looks at them or hears about them and they form a stereotype,” Barone said, adding that he would have liked to see the trial moved to one of the boroughs of New York City or Erie county, where there is a bigger Arab American population.

After he was arrested, Matar gave an interview to the New York Post in which he described taking a bus to Buffalo from his home in Fairlawn, New Jersey, and a Lyft to Chautauqua, 40 miles away. He then purchased a ticket to the festival and slept outside the night before Rushdie’s talk.

“I don’t like the person. I don’t think he’s a very good person,” Matar told the newspaper. “He’s someone who attacked Islam. He attacked their beliefs, the belief systems.” Matar also praised the late Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini as “a great person” but would not say whether he was following Khomeini’s fatwa.

Nasser Kanaani, a spokesman for Iran’s foreign ministry, said Tehran was not involved. “We don’t consider anyone deserving reproach, blame or even condemnation, except for [Rushdie] himself and his supporters. In this regard, no one can blame the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

Kanaani added: “We believe that the insults made and the support he received was an insult against followers of all religions.”

Ron Kuby, who represented Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the blind cleric who headed the Egyptian-based militant group al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, said it was no surprise Matar refused to take a deal with prosecutors.

“I suspect he thought he was going to be killed in the course of this attack so his expectations were low. He was fortunate enough to survive it so he’s probably going to continue the fight inside the courtroom and in prison,” he said.

Kuby said he wondered if Matar would opt for a traditional defense by trying to create reasonable doubt and challenge eyewitness accounts or instead talk about his motives behind the attack.

“Is he or his lawyer going to put on a more ideological or religiously inspired defense and talk about the religious values that motivated him to try to kill Rushdie, The Satanic Verses, and try to put on a political defense?” Kuby said.

In Knife, Rushdie himself described the attack vividly, writing, “Death was coming at me … it struck me as anachronistic”, and described his alleged assailant as “a sort of time traveler, a murderous ghost from the past”.

The courtroom collision of Rushdie and his alleged attacker is likely to be fascinating, especially if Matar tries to turn the trial into a justification of attacking the writer for the offense his work caused.

“Matar allegedly tried do it on that stage that day, and may continue to do it in the courtroom even though it’s going to result in his conviction,” said Kuby. “Sometimes people prefer to get a conviction than to give up their conviction.”

.png) 2 months ago

31

2 months ago

31