In June 1986, a pair of operatives from communist Czechoslovakia’s StB intelligence service made contact with a mysterious couple staying at a Prague hotel. The man’s passport identified him as a Syrian diplomat called Walid Wattar; his pregnant wife also had a Syrian diplomatic passport.

In fact, the man was Venezuela-born Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, better known as Carlos the Jackal, perhaps the world’s most wanted terrorist at the time. He was with his wife, Magdalena Kopp, recently released from French prison.

Ramírez Sánchez spent a lot of time behind the Iron Curtain and was known to receive support from both the KGB and East Gemany’s Stasi. But a new book based on the archives of the Czechoslovak secret police suggests the picture of Communist bloc support for him and other violent radical actors during the late cold war period is not so simple.

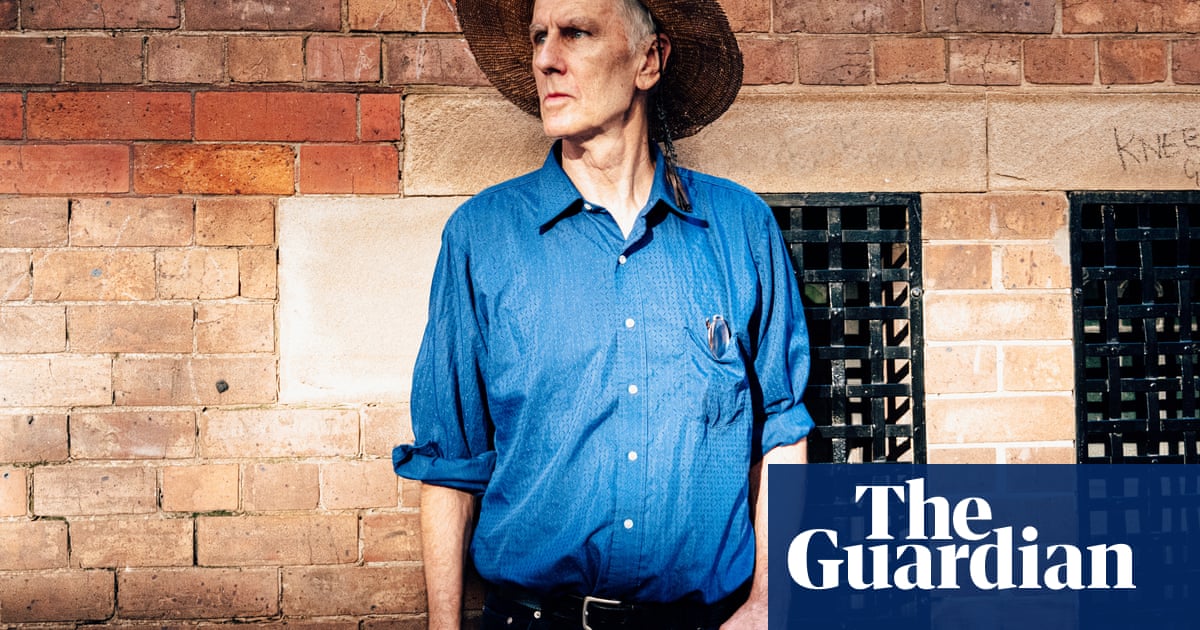

“There was this dramatic Reagan idea that the Soviets and all the other services were training them, giving them whatever they needed and then directing them to carry out attacks in the west,” said Daniela Richterova, a specialist in intelligence studies at King’s College London and author of the new book, Watching the Jackals. “In fact, the reality was more complicated.”

In this particular instance, the Czechoslovak agents told Ramírez Sánchez and his wife that they knew who they really were, and that they had information that French intelligence operatives were in Prague and on a mission to “liquidate” them. The officers advised them to leave the country immediately. Within hours, Ramírez Sánchez was on a flight out.

But the supposed French plot was fictitious; the StB simply wanted Ramírez Sánchez, who with his associates had been responsible for a wave of terror across Europe over the previous decade, out of the country, fearful of his reputation and his methods.

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, communist Prague often acted as a haven for operatives from revolutionary and terrorist movements from across the globe, who used Czechoslovakia as a safe place for meetings, planning and sometimes liaisons with the local authorities.

Richterova worked in the archive of the former Czechoslovak security service in Prague, which has made all but a small handful of its Communist-era documents open for viewing, giving an unprecedented insight into the links between Czechoslovakia and various violent non-state actors during the cold war.

The archives show that there was a particularly close relationship with Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organisation, and the book details the extensive relations between the PLO’s security service, led by Arafat’s No 2, Abu Iyad, and Czechoslovak authorities.

A 1981 visit by Iyad to Prague resulted in agreement on a package that included intelligence exchange, joint operations, arms supplies and security training. Files suggest officials in Prague even discussed an operation in which the Palestinians would target Czech dissidents living abroad and either assassinate or kidnap them, though the discussions came to nothing.

Though there were times when the Czechoslovaks cosied up to Middle Eastern groups, there were many more occasions when it was clear Prague was confused and alarmed by the presence of Arab operatives on its territory and struggled to keep tabs on them. While there were deep links with the PLO, the StB remained wary of more radical Palestinian groups, as well as of rogue actors such as Ramírez Sánchez.

The full story on Moscow and the KGB’s relations with these groups remains locked away in the Russian archives, but the Czechoslovak documents make it clear that “there was no coordinated policy and no direction from the Soviet Union”, said Richterova.

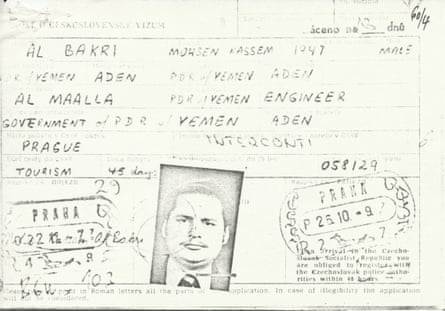

The book also shows that the communist-era intelligence service, so feared when it came to domestic dissidents, was less than impressive when it came to tracking these foreign groups, whose members often had a whole stash of diplomatic passports under various identities issued by Middle Eastern countries.

“The StB operatives didn’t speak Arabic, they didn’t quite understand who is a member of what group, and when they put them on these persona non grata lists it didn’t work at all,” said Richterova.

The political and moral dilemmas of how to track radical groups, and to what extent to cooperate with them when certain objectives might align, has continuing relevance today. With the KGB archive in Moscow firmly closed, the Czechoslovak documents are a rare insight into the way those dilemmas were handled and discussed in the Soviet bloc. They are also more instructive than anything available in the west where, in the UK for instance, MI6 archives remain closed.

“It’s about how states use their spies to interact with dangerous individuals, some of whom they want to align with and some who they don’t. It’s always a complicated business and a difficult dance,” said Richterova.

.png) 3 months ago

51

3 months ago

51