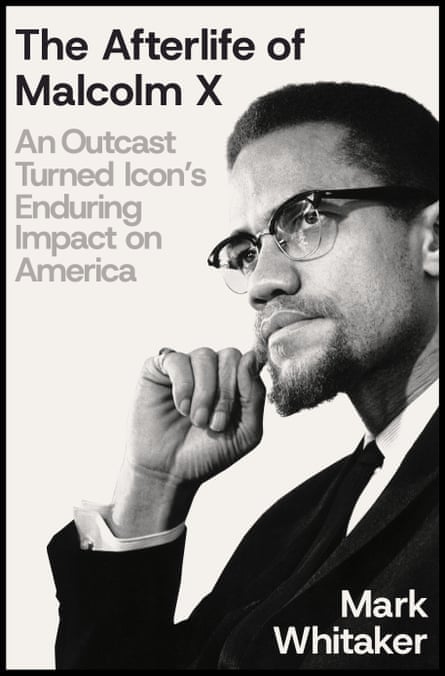

The Afterlife of Malcolm X is a new book about the great Black leader who was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, 100 years ago; who in the 1950s converted to Islam and dropped his “slave name”; who rose to fame as the militant voice of the civil rights era; and who was assassinated in New York in 1965, aged just 39.

The book is not a biography. As the author, Mark Whitaker, puts it, his book tells “the story of the story of Malcolm, the story that really made him the figure he is today, even more so than what he accomplished while he was living.

“So it was the story as told by Alex Haley in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. It was the story as told by Spike Lee in the movie, Malcolm X. It was the story as told by his biographers. It was the story that is told in hip-hop, and in Anthony Davis’s opera, X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X. And it changes over time. Each of those stories is a little bit different.”

Whitaker has told many stories himself. Now 67, a CBS contributor, he was editor of Newsweek, Washington bureau chief for NBC and a managing editor for CNN. His new book is his fifth. As well as a work of cultural history it is a true-crime thriller, tracing the story of who really killed Malcolm at the Audubon Ballroom in Washington Heights, and how two men wrongly imprisoned were finally cleared.

The book grew from two others: Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Black Renaissance and Saying it Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement. Smoketown, about “the legacy of Black Pittsburgh … ended in the early 60s”, but Whitaker “had done all this reporting about … Black America in general in the civil rights era, and so I wanted to pick up that thread. I decided to write about the birth of Black Power, specifically in 1966. A lot of people would say, ‘Oh, so you’ll be writing about Malcolm X.’ And initially my response was, ‘No, he was assassinated in 1965.’ But the further I went, the more I realized he loomed over all of it.

“’66 was the year the Autobiography was released in paperback and really became a bestseller. Meanwhile, he was in the heads of all of the major figures. Stokely Carmichael at the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver, founding the Black Panthers; Ron Karenga, who had this sort of Black nationalist movement in LA and was the founder of Kwanzaa; the first proponents of Black studies on white campuses. All of them drew their inspiration from Malcolm X.”

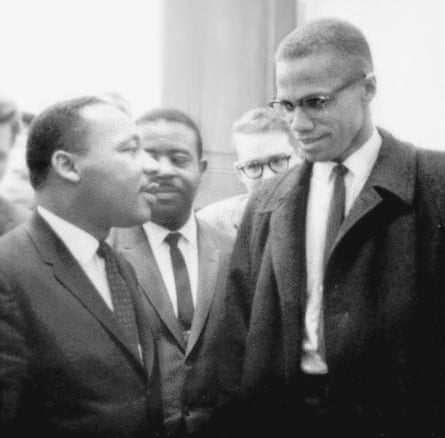

As a teen, Whitaker read the Autobiography. It told him Malcolm’s story, from brutal youth to street hustling, prison, conversion, and his rise in sharp contrast to Martin Luther King Jr, the voice of nonviolent action. Whitaker knew about the split with the Nation of Islam and its founder, Elijah Muhammad, that precipitated Malcolm’s killing. In 1992, Whitaker covered Spike Lee’s movie for Newsweek. In 2020, for the Washington Post, he reviewed The Dead Are Arising, a major biography by Les and Tamara Payne that followed Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marable, which won a Pulitzer Prize.

Seeking to publish in Malcolm’s centennial year, Whitaker had to work quickly. But if “life as a journalist trained me to do anything, it trained me to meet a deadline”.

“Obviously there have been aspects of this that have been written about,” he added. But though he doesn’t “want to be immodest” he doesn’t think “anybody’s really put it together in the way that I have”.

Malcolm’s story has often been told.

“Each one of those stories is a little bit different,” Whitaker said. “And sometimes they’re at odds. If you read the biographies and what was written about them, each one was trying to kind of revise and correct the story. So a lot of people think that Alex Haley, though it was he who kind of brought Malcolm to life for the reader, [produced] a sanitized version. Alex Haley was a moderate Republican, and he sort of massaged the narrative to emphasize Malcolm’s evolution in the last year and leave the reader with the impression that he was really sort of gravitating in the direction of becoming more of a mainstream, conventional civil rights leader.

“Marable was trying to correct that and paint Malcolm as someone who remained radical, to focus less on his change of heart towards white people, and more on his Pan-Africanist ambitions, on his global travels. Then Les Payne comes along … [he] had been sitting on all of this exclusive reporting for decades, and so it’s less of a correction about Malcolm’s politics, and more adding heavily reported detail on key episodes in his life.

“I wasn’t taking sides. I was trying to show that one of the things that’s fascinating about Malcolm is that he has had all these different interpreters, and I argue in the introduction that ultimately they’re not mutually exclusive, that one of the things that’s fascinating about Malcolm is that almost at any point in his evolution, he represented many different things. He seems like a radical. He seems like a conservative. He’s a traditionalist. He’s a modernist.”

Whitaker considers how such influence extended to sports, to athletes including the boxer Muhammad Ali and the sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who raised their fists at the Mexico Olympics in 1968. More surprisingly, Clarence Thomas, the second Black justice on the supreme court, a reactionary conservative, has long cited Malcolm’s example.

“There are people who are appalled that Thomas would claim any kind of kinship,” Whitaker said. “But I think there are two aspects of Malcolm’s message that spoke to Clarence Thomas. One was sort of ‘self-help’, support for Black-owned businesses and so forth. But the other was skepticism about integration.

“And although it is true that Malcolm, after he went to Mecca [in 1964] and he saw white Muslims and so forth, came back and said, ‘I no longer think that all white people are devils’, and certainly he had sort of [white] friends – I don’t know to what degree you could really call Peter Goldman and Helen Dudar, or Mike Wallace or Bill Kunstler friends, but they were certainly people he felt comfortable enough with – I think he remained skeptical, and to my mind rightly so, of just how prepared America really was to become truly integrated.”

Goldman and Dudar, a married couple, were journalists, Goldman the author of The Death and Life of Malcolm X, an influential study from 1973. Mike Wallace was a CBS TV host who interviewed Malcolm. Kunstler was a civil rights lawyer.

Whitaker continued: “I think another reason that Malcolm has continued to resonate over the decades is that just on a purely analytical level, I think his analysis of race relations in America has turned out to be … more prophetic than King’s. Sixty years later, we’re not that much further toward King’s dream. I think obviously the workplace has become more integrated, in movies and TV and so forth [too], but in terms of where Americans live, neighborhoods, famously, where they worship, if they do worship, the progress has been much less than I think a lot of people thought it would be by this point – and now we’re in the midst of yet another backlash against all the progress that’s been made.”

The Trump administration is attacking the teaching of Black history. It’s hard to imagine Whitaker’s book, or any other on Malcolm X, studied at West Point or Annapolis any time soon.

“None of that would have surprised Malcolm X,” Whitaker said. “So … there are people who just refuse to accept that Clarence Thomas invokes Malcolm X in good faith, but I don’t. I actually think that at least in Thomas’s mind, he does very much see that part of Malcolm’s message as one that aligns with his thinking.”

Whitaker had no choice but to think along multiple lines.

“Just by studying Malcolm’s influence, you get a sort of a cultural history of Black America and of America over 60 years,” he said. “You find out about the Black Arts Movement, you learn a little bit about Hollywood, you find out about the free jazz movement, you find out about the birth of hip-hop … I’m sort of a jazz guy myself. So it was fun to become more knowledgeable.”

Asked about the notion that Malcolm and King can be seen in a jazz frame, Malcolm as Miles Davis, edgy and cool, King as John Coltrane, spiritual and high-flown, Whitaker said: “That was Anthony Davis, what he said about how he thought of Malcolm’s voice in writing the opera”, a production revived after 2020, the summer of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter.

As Whitaker worked, another dual vision loomed large: Peniel Joseph’s The Sword and the Shield, which posits Malcolm as the sword and Martin as the shield of Black Americans striving for justice. Such contrasts will forever be drawn. Whitaker makes his own.

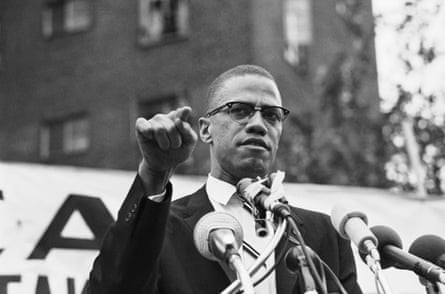

“There’s a lot of discussion today about what kind of communication works politically, with the transition to social media, podcasting and so forth. People are saying politicians who are effective are the ones who speak in a more direct way, in a more conversational way, and with more humor. That was all Malcolm. King is still very impressive, when you go back and you listen to his speeches, but he always sounds like he’s talking to you from a pulpit. Malcolm always had this incredibly direct conversation, very powerful, and that’s why he was so great.

“He went around and talked on college campuses and engaged in panels and debates on TV and on radio, and it still feels very contemporary. King’s voice, as important and majestic as it was, feels like an artifact of history. Malcolm … you go on YouTube and you listen to his speeches, but even more so his interviews, and it feels like he could be talking today.”

-

The Afterlife of Malcolm X is out now

.png) 5 hours ago

3

5 hours ago

3