Witnesses recall seeing a woman and two children crying out “no, stop”. A man carrying a small girl to his car. Her head banging into the door as he bundled her into a seat. No time to fasten her seatbelt.

“You have caused all of this, it’s your fault,” Rowan Baxter said to his estranged wife, Hannah Clarke, as he drove off with their daughter, Laianah, on Boxing Day 2019.

Eight weeks later Baxter filled a jerry can with petrol, poured it into the family car and set it alight. The children – Aaliyah, six, Laianah, four, and Trey, three – were killed instantly and Baxter took his own life soon afterwards. Clarke died in hospital from her injuries.

The deputy state coroner Jane Bentley found in 2022 that it was “unlikely that any further actions taken by police officers, service providers, friends or family members could have stopped Baxter” from murdering his family.

But Guardian Australia has uncovered new evidence – some of it never investigated by police and overlooked by the coroner – that provides fresh insight into those critical final weeks of Clarke’s life as she sought to escape Baxter.

It casts doubt on that finding.

It shows significant police lapses in the weeks between the abduction and the murders – including failures to adequately investigate or document Clarke’s allegations of non-lethal strangulation, stalking, phone hacking, rape and suspected child abuse.

Those failures meant risk assessments were not updated with information that would have flagged Clarke as being at an extreme risk of harm and prompted further protective action.

A whistleblower from within the coronial system who raised concerns about the police and coroner’s handling of the case to the Crime and Corruption Commission told Guardian Australia the homicide investigation did not consider evidence of mistakes and other “embarrassing failures” by police before Clarke died, and was led by an officer with a potential conflict of interest.

The Queensland police service has never conducted an internal investigation or review into its handling of the case. Instead, after Clarke and the children were murdered, detectives turned the spotlight on the victim – questioning whether she had fabricated her claims of domestic and family violence against the man who killed her.

Twisting the narrative

Guardian Australia applied for access to Clarke’s coronial inquest file in late 2023. In May 2025 the coroner’s court released a number of exhibits that have not previously been released to the media, including police body-worn camera footage from 29 December 2019, three days after Baxter’s abduction of Laianah.

The footage was played at the inquest but reporting at the time focused on Baxter’s behaviour, rather than that of the police. It shows officers arriving at Baxter’s property to serve him with a protection notice that requires him to return the four-year-old to her mother and prohibits him from approaching the children or Clarke’s home.

It offers insight into how Baxter sought to twist the narrative and portray himself as a victim. It also shows two officers telling him how he might challenge the police protection order in court.

Baxter clings to Laianah as he speaks to the officers, while a Peter Rabbit cartoon plays on the television. He acts shocked and says, “Oh my gosh, how ridiculous.”

He blames Clarke and says she’s “playing games”. He acts distraught and turns his head as if holding back tears.

“I have not done anything to warrant any of this,” he says when told the order relates to allegations of domestic violence. “I would never, ever do that.”

The two officers begin to instruct him how he might challenge the order.

One advises him: “Talk to your friends about, you know, someone who might be willing to provide a reference about you or something like that.”

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

The other interjects: “To say you are a good dad and … don’t need any conditions.”

Baxter tells the officers he has been given legal advice to stay away from Clarke “because she’s likely to do a [domestic violence order] on you … he says they can do it for anything”.

“They can,” the first officer says. The body-worn camera is then switched off – in an apparent breach of protocol – as the police continue to speak to him.

The officers’ comments were not mentioned in the coronial findings.

A former senior detective, Kate Pausina, who reviewed the footage says: “In all my years policing I’ve never seen officers coach an offender who was accused of stealing.

“Why would you do it in the case of domestic violence?”

Guardian Australia also showed the footage to the Queensland police deputy commissioner Cameron Harsley. He said there had been a “crossover” in the case between domestic violence and custody issues but that the job of police officers was “to administer the law, not to give legal advice”.

“Our job is to issue those orders,” he said. “I don’t accept police giving legal advice to perpetrators.”

A growing friendship

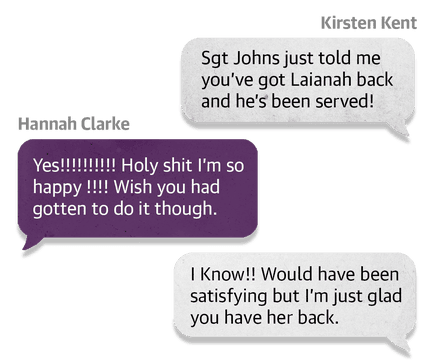

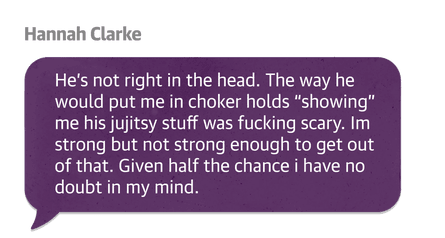

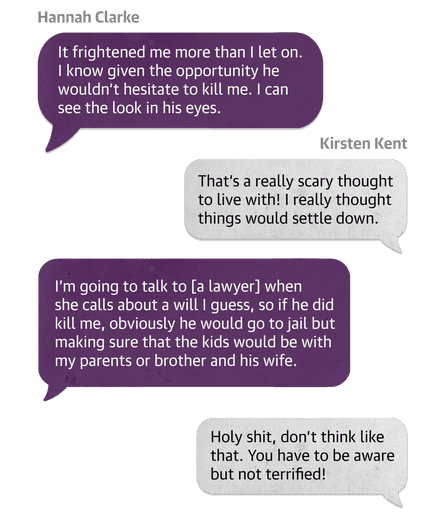

The coroner also released more than 200 pages of text messages between Clarke and Kirsten Kent, a specialist domestic violence police officer who was assigned to her case and developed a friendship with her.

The coroner praised Kent in her findings and said she “did everything she reasonably could to protect and assist Hannah”.

“She identified that Hannah was a victim of DV when Hannah had not recognised that herself,” the finding says. “She supported Hannah at a time when Hannah needed professional support.”

In late 2019 Kent sought advice from the “vulnerable persons unit”, a specialist police unit that manages domestic violence cases. She took affidavit statements from Clarke in which she disclosed fears she would be killed and said Baxter forced her to have sex with him.

She instigated the police protection notice after learning Baxter had taken Laianah and conducted a risk assessment on the same day, determining that Clarke was “high risk”.

After Laianah was returned, the women began to communicate regularly via text. It is clear from the messages that Clarke viewed Kent as both a friend and a police contact.

Clarke’s claims not recorded

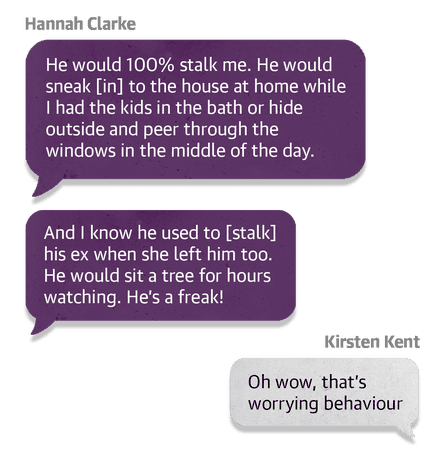

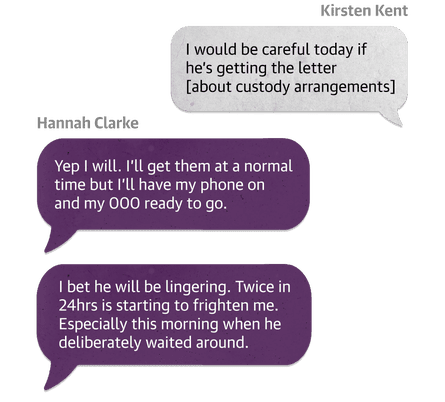

In the text conversation between the pair, Clarke says she believes Baxter is “stalking” her and questions how he knows about her movements and conversations.

She shares concerns about Baxter turning up repeatedly at her regular coffee shop and noticing him “lingering” nearby.

Clarke told Kent about a visit to the Carindale shopping centre where she believed Baxter was following her. The officer looked up CCTV footage and sent messages to Clarke about it.

Kent told the inquest it appeared that Baxter was shopping. She said she had considered treating the stalking allegations as a criminal complaint but “did not push Hannah into making one for several reasons”, including that Clarke had not wanted to do so.

“I investigated the incidents and did not consider there was enough evidence to pursue a stalking complaint but rather that I could use the incidents as evidence for the [domestic violence order].”

The disclosures were not recorded in the police Qprime data system.

On 22 January, as Clarke prepared to attend a court hearing, Kent advised her to “maybe just keep our new friendship on the down low”.

“There’s nothing wrong with us being friends but I don’t want him having any ammunition,” she said. “They could say I’m biased and took the order out cos we’re friends not because you need it.”

The assault

On 30 January the children spent the night at Baxter’s house. Clarke told Kent that Laianah needed to be “pried off me with her fingernails dug in” and that Aaliyah hadn’t wanted to go.

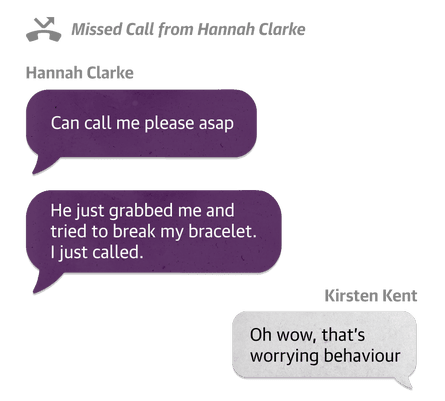

The next morning Baxter assaulted Clarke in the driveway of her parents’ home. She immediately called Kent.

Baxter had printed out photographs of Clarke posing in her underwear, which he later said were “for court”. They were on the back seat of the car when he returned the children to Clarke’s parents house.

When Clarke reached into the vehicle to try to retrieve the photographs, Baxter grabbed her arm and twisted it. Police charged him with assault occasioning bodily harm and breaching the domestic violence order but later downgraded the charge to common assault. The decision was not made by Kent. The coroner would describe the downgraded charge in her findings as a “missed opportunity”.

The next day Kent sent a message to Clarke to warn her that Baxter was aware of their friendship, including that Kent had invited Clarke and the children to her home for a swim in the pool.

The day after that Kent attended Baxter’s home with another officer to interview him about the alleged assault.

In her statement to the inquest Kent said she had been told by senior officers to remain unbiased and that thereafter she had been “mindful not to converse back too frequently” in texts to Clarke.

A whistleblower complaint to the CCC says police failed to address or investigate how the relationship between Clarke and the officer “likely escalated the risk” she faced from Baxter.

After the killings, investigators found a note written by Baxter and addressed to Clarke that indicated he had become agitated by the friendship.

“You have a social attachment with her,” he wrote.

Baxter’s escalating behaviour

The assault was a critical moment when it should have been recognised that Baxter’s behaviour was escalating, experts say. In its aftermath, Clarke made a number of new disclosures to Kent about his prior behaviour.

Her disclosure about being placed in a jujitsu hold is an allegation of non-lethal strangulation – a criminal offence in Queensland since 2016. Officers receive training in how to recognise and respond to it.

The risk of intimate-partner homicide is seven times greater in cases where non-lethal strangulation has occurred, research shows. But a review by the state’s Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board found that Clarke’s allegations to Kent of non-lethal strangulation, stalking and other behaviours had not been entered into the QPrime system.

This means other officers would not have been aware of some of the claims that Clarke had made about Baxter’s behaviour in her text messages to Kent.

The whistleblower from within the coronial system says in her disclosure statement to the CCC that this amounted to a “missed opportunity for police to have intervened”.

“The failure to appropriately document reports of domestic and family violence on QPrime means officers responding to future events are less likely to complete an adequate risk assessment,” the statement says.

“This was not explored by police in the homicide investigation or by the coroner at inquest.”

Risk assessment ‘not consistent’

The same night Clarke disclosed non-lethal strangulation, she also expressed new fears she would be killed.

In the weeks after Laianah’s abduction – as Clarke disclosed new information and Baxter’s behaviour escalated – it appears that no further risk assessment was completed by the police after the one done by Kent on 28 December.

Heather Douglas, a law professor at the University of Melbourne, told the inquest the risk assessment by police officers “was not consistent”.

The Queensland Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Unit also completed a report for the inquest that said national principles outline that risk assessments should be “continuously assessed, reviewed and actively managed”. That did not happen in Clarke’s case.

“Lethal risk can escalate quickly (within hours or days) within the context of intimate partner violence perpetration and it is critical that agencies are able to rapidly identify and respond to the changed risk level,” the report said.

“While Hannah was identified as high risk by both [a domestic violence service] and police, there does not appear to have been any consideration by either agency of the need to escalate the service response when she sought further advice and support from them.”

The unit said police should have investigated Clarke’s disclosures of non-lethal strangulation, stalking and rape.

after newsletter promotion

“Pending consideration of whether there was sufficient evidence to pursue criminal charges, investigations by police in relation to these offences may have provided an opportunity to implement strong bail conditions against Rowan that would have allowed for more intensive monitoring of him.”

The report notes that if a risk assessment had been conducted in the weeks before the murders – after Baxter assaulted Clarke – with information Clarke had disclosed to police it would have found her at “extreme” risk, meaning that “an incident could happen at any time and the impact could be serious”.

During February, Clarke began to raise concerns that Baxter had been hacking her phone. She told Kent several times that Baxter appeared to know about her movements and private conversations.

When Clarke signed up to a new gym, Baxter announced on Instagram the next day that he was also joining the gym in a “coaching role”.

Clarke sent the post to Kent with a message: “Told you he’s stalking me … he would have known through my old phone I was planning on going there.”

In affidavits Clarke wrote that a technical expert had found possible evidence of an email that would allow access to spyware.

Baxter’s possible phone-hacking, and how he knew about Clarke’s movements and her interactions with Kent, were not explored in the homicide investigation or at the inquest.

‘Obligation to record’ allegations

In her statement to the inquest, Kent said that throughout all her communication with Clarke: “I always placed both her and the children’s safety and wellbeing first.”

She said she had spoken to her officer-in-charge about their friendship.

“Clarke was a lovely girl and I enjoyed speaking to her,” she said. “I was aware that I was a bit too personally involved. From this conversation [with the senior officer] I understood that whilst I could continue to provide support, I was to remain unbiased.

“I understood this and made an effort not to converse with Clarke as often.”

Pausina, who worked as a police liaison to the coroner and has extensive experience reviewing domestic and family violence deaths for evidence of policing failures, has reviewed the text messages and other evidence.

She says it’s clear that Kent believed Clarke when other officers did not.

“It’s evident that she showed genuine care for what was happening and that she understood what was happening,” Pausina says.

“My personal opinion is that the relationship had moved beyond being a professional relationship into more of a friendship… But that’s OK, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

But she says by not recording or further investigating the “serious allegations of criminal offences” from the text messages, Kent failed in her professional duty to Clarke.

“If Hannah was disclosing information about domestic violence that is actually occurring at the time, that officer still has an obligation to record that information that she’s been provided on the police database.

“They are serious allegations of criminal offences.”

The police service said it acknowledged the coroner’s findings that commended Kent and “noted that the organisation acted appropriately in its response”.

“It is recognised that officers responded based on the information and understanding available to them at the time, in alignment with the organisation’s values of integrity, respect, and courage.

“Since the murders of Hannah, Aaliyah, Laianah and Trey, the service has continued to evolve and learn; strengthening its response to domestic and family violence but recognising there is still more to achieve.”

The night before she was murdered, Clarke sent a final text to Kent.

She was worried about Baxter’s demeanour and said he had “sobbed down the phone” while speaking to his children. “I think everything is catching up on him now,” she wrote. “I know he has brought all of this on himself.”

Kent was on leave and interstate with no phone reception. By the time she saw the message the next morning, Aaliyah, Laianah and Trey were dead and Hannah was dying.

The homicide investigation

Two days after Clarke and her children were laid to rest in a shared white coffin, detectives visited the state coroner’s office to provide a confidential briefing about their homicide investigation.

Police had begun the case on the back foot. The first detective assigned to the case, Mark Thompson, was stood down over “victim blaming” comments at a press conference. For weeks between the killings and the funeral, Hannah and her children became the object of collective grief; perhaps the most prominent domestic and family violence killings since the murder of Luke Batty 10 years earlier.

Police had given the case a codename: Operation Sierra Pontoon. By the morning of the meeting on 10 March 2020, officers had taken more than 180 formal statements from witnesses.

The basic facts were clear: Baxter had killed himself after killing his family, as Clarke and the children headed to school.

The police investigation was no whodunit. Operation Sierra Pontoon’s purpose was to understand why the killings had occurred and if anything could have been done to stop them.

Clarke had formal contact with police at least 16 times before her death, not including the messages between her and Kent. But the homicide investigation did not investigate or review the police response.

Instead, three weeks after the killings, detectives turned the spotlight on the victim.

In a document from the meeting with the coroner, leaked to Guardian Australia last year, police questioned the “veracity” of Clarke’s allegations of domestic and family violence, and her “motive” for seeking a domestic violence order against Baxter.

Police proposed investigating issues such as the legal advice Clarke received to prevent Baxter’s access to the children and the “ongoing custody dispute”. They also proposed investigating whether Baxter had a hypothetical defence against the assault charge on grounds he was defending his property – the intimate photos of Clarke.

According to the whistleblower complaint to the CCC, the officer who took over the investigation and wrote that document, Det Sgt Derek Harris, had a potential conflict of interest because he had been the officer responsible for assessing a “child harm referral” after Baxter abducted Laianah.

According to the inquest findings he ultimately declined to investigate the abduction on the basis there were no formal parenting orders in place, he believed there was no imminent risk of harm to Laianah or her siblings and it amounted to a “custody dispute” rather than a criminal offence.

He forwarded the matter to the Department of Child Safety.

“My role as a detective is to investigate crimes against children … unfortunately it is very black and white,” he told the inquest.

The CCC assessed the coronial system whistleblower’s allegations and found that allegations that Harris had a conflict of interest, if proven, “would not meet the standard of the conduct the community reasonably expects of a police officer”.

It declined to investigate further on the basis the allegations were considered to amount to “police misconduct” rather than “corrupt conduct” because they were not serious enough to result in criminal charges or sacking.

‘Wrongdoing, errors, incompetence’

The whistleblower complaint says Laianah’s abduction “should have resulted in immediate actions being taken by police (and other services) to protect Ms Clarke and the children”, such as an urgent referral to high-risk teams.

It says that because the police response to Clarke before the deaths was a matter for consideration by the inquest – and the abduction was a critical moment – Harris as head of the homicide investigation and reviewing the police response for the coroner had been effectively ordered to “investigate himself”.

“An officer being tasked to investigate himself cannot do so impartially,” it says. “Given Detective Sergeant Harris was involved in the service delivery, there is no reason he should have been tasked to investigate this case.”

The whistleblower claims that critical evidence of “wrongdoing, errors, incompetence and/or otherwise embarrassing failures in response to Ms Clarke’s reports of domestic and family violence and child abuse and Mr Baxter’s identifiable pattern of escalating violence and risk” was overlooked during the homicide investigation and not addressed by the coronial inquest.

An independent review of investigations into domestic violence-related deaths in Queensland was told that the brief of evidence in the Clarke investigation was poor quality and missing relevant documents and reports.

Police are required – under the operational procedures manual – to conduct a “homicide audit” that documents all contact between police and a victim in a domestic or family violence death. No such audit was produced by police for the inquest. The coroner did not note this failure.

The coroner found there had been “missed opportunities” for authorities to intervene, including the downgrading of the assault charge that meant Baxter was given a notice to appear in court rather than taken into custody and placed on bail. She noted that there was no apparent reason for the downgrade.

The inquest identified that there had been “a failure by all agencies to recognise [Baxter’s] extreme risk of lethality” and “a failure to recognise the risk of intimate-partner homicide which results from separation in a coercive controlling relationship”.

A spokesperson for the coroner’s court said coroners did not comment on their findings and that there were avenues for review including appeals.

“The coroner may inform themselves and gather information in any way they see fit,” the spokesperson said.

“Where appropriate, relevant agencies may undertake their own regulatory, disciplinary or internal investigations and reviews, separate to the coronial process.”

Police doing ‘the best they could’

Harsley told Guardian Australia that police “always believe the victim”.

“We’ve got to act on it at face value,” the deputy commissioner said. “I think in Hannah’s case, I’m confident the police were trying to do the best they could.”

When shown the investigation document in which detectives questioned the veracity of Clarke’s domestic violence allegations even after she died, Harsley said: “I don’t know what was actually on their mind, the judgment that they were using. But … it is quite obvious that the behaviour leading up to Hannah’s death was coercive control behaviour.”

He conceded, from the evidence shown to him by Guardian Australia, that “you could have the perception” that the investigator’s questioning of Clarke’s allegations might be interpreted as the officer trying to justify his own actions before her death.

“There’s a range of checks and balances put in place … there’s also oversight from the ethical standards command and the CCC,” Harsley said.

Neither of those bodies has investigated this matter. Asked why police had not investigated their own response for the inquest, Harsley said the “vulnerable persons unit” had done a review. It was not given to the coroner and has not been made public.

Harsley called domestic violence “a social issue”.

“If you’re going to think police are the answer to this problem, you’re misleading,” he said. “Weak men hurt women, and hurt their community. Strong men protect their community and protect their families.

“I believe that we do a very good job in the majority of cases. But do accept, in some cases, we are not living the standards that are expected of the Queensland police service. I accept that.

“I accept that we need to change. I accept that our culture – we’re on a journey to try and get that better. It’s not a thing you can do overnight.

“Even if you have a perfect police response, we’re not going to stop homicide, domestic homicide.”

Asked if she believes more could have been done to protect Clarke and her children, Pausina says: “Absolutely.”

“I believe as police officers we should view every domestic and family violence homicide as preventable.”

Cameron Harsley retired from the role of deputy commissioner of the Queensland police service in September

In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and the national family violence counselling service is on 1800 737 732. Other international helplines can be found via www.befrienders.org

Do you know more? Contact [email protected]

.png) 2 hours ago

5

2 hours ago

5