A poll suggests that most British Muslims identify more with their faith than with their nation. The head of the Saudi-backed Muslim World League counsels British Muslims to talk less about Gaza and more about domestic issues. Labour MP Tahir Ali is criticised for campaigning for a new airport in Mirpur in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir; he claims the criticisms have led to “Islamophobic” attacks. After push-back, the BBC changes a headline describing converts to Islam as “reverts”, a term some Muslims use to suggest that Islam is the natural state of humankind.

Just a taster of debates about British Muslims over the past week. At the heart of each of these controversies is the question of how Muslims should relate to western societies, and western societies relate to them. For some, the answer is easy. On the one side, many claim Islam to be incompatible with western values and that allowing Muslims to settle here has led to what they regard as the degeneration of western societies. On the other are those who insist there is no issue, and those who raise concerns are bigots. Both are wrong. There are issues about Muslims and integration that need discussing, but those issues are rarely as presented in these debates.

Part of the problem is a view of Islam as fixed and static, a belief that it has remained the same throughout history, as have Muslims’ beliefs about their faith. It is a perspective ironically shared by dogmatic Islamists and implacable critics of Islam. In reality, not only are Muslims as diverse as any other community, but their connection to their faith is constantly evolving. To understand Muslim attitudes and attitudes to Muslims, we need to track that changing relationship between Muslims, their faith and wider society.

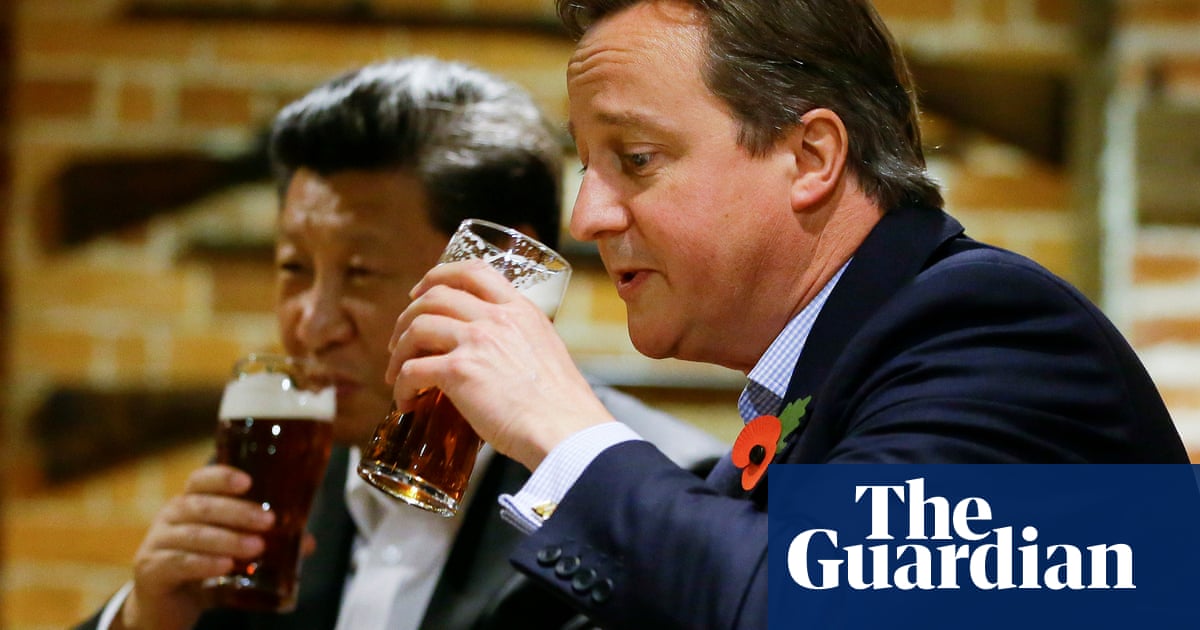

The first generation of postwar Muslim immigrants to Britain, largely from the Indian subcontinent, was pious and culturally conservative, but wore its faith lightly. Many men drank alcohol. Few women wore the hijab.

The second generation – my generation – was more secular. Our desire for equality led us to challenge not just racism but the obscurantism of mosques and faith leaders. The more hardline strands of Islam had little sway within British Muslim communities until the end of the 1980s. The irony is that, since then, a generation of Muslims far more integrated and “westernised” than the first came also to be the generation most insistent on maintaining its “difference”. A study by the Institute for the Impact of Faith in Life (IIFL) published last month found that young people were most likely to view themselves as Muslim more than British, while over-65s were twice as likely to identify as British first.

The reasons for the transformation of attitudes are complex. Partly they lie in international developments such as the battle between Saudi Arabia and Iran for leadership of the global ummah that led to Saudi petrodollars helping fund more hardline Islamist organisations in the west. Partly they lie in the rise of identity politics and of narrower conceptions of belonging. And partly they lie in public policies driven by a perception of the nation as a “community of communities”, in the words of the influential Parekh report on multicultural Britain. State institutions began relating to minority communities through “community leaders”, often religiously conservative men who used their relationship with the state to cement control over their ethnic fiefdoms, encouraging social division along lines of identity.

Many institutions and policymakers came to regard socially and religiously conservative Muslims as more “authentic”, often dismissing those with liberal views as not being truly of their community. The BBC’s use of “revert” to describe “converts” may well have come from a desire to portray what it took to be an authentically Muslim view.

The more inward-looking, conservative character of many Muslim communities today has been forged out of social and political developments rather than simply from religious conviction. Nor are identitarian forms of belonging unique to Muslims. A report last year for the Institute for Jewish Policy Research found that most British Jews had “a stronger Jewish identity than British identity”. Around three-quarters felt “attached” to Israel, especially in the wake of the 7 October Hamas attack, and this framed the response of many (though not all) Jews to the Gaza conflict.

For many Muslims, too, their identity is shaped in part by the Palestinian struggle, and they feel distraught about Israeli attacks on schools, hospitals and civilians. Unlike with Jewish identity, though, this gets condemned as “sectarian”. What is sectarian is not support for the Palestinian cause, or opposing the destruction of Gaza, but to view these purely through the lens of Muslim identity. It is defining attitudes to political issues by the boundaries of identity rather than by political and moral reasoning that makes it sectarian.

Sectarianism has long existed in British politics. For decades the Labour party, in cities such as Bradford and Birmingham, has exploited a machine politics based on the biradari, or clan, system that could deliver bloc votes to particular candidates. Today, that old machine politics has been folded into the politics of identity.

Tahir Ali’s constituency of Birmingham Hall Green and Moseley is beset with social and political problems, from the bin strike befouling the streets to the worst child poverty rate in Britain. He seems largely to have ignored the strike and has never voted in parliament on issues of welfare reform or in opposition to benefit cuts. He has, however, been campaigning for the reintroduction of blasphemy laws and pressing the Pakistani government to build an airport in Mirpur. MPs have every right to engage on foreign issues. It is difficult, though, not to view his record as being defined by sectarian interests.

after newsletter promotion

British Muslim attitudes are shaped also by a sense that non-Muslims see their faith but not their Britishness. It is this perception, rather than any deep attachment to Islam, the IIFL study suggested, that drew Muslims to identify with their faith more than with their nationality.

The growing clamour that Muslims don’t belong in the west, a sentiment often attached to a desire for Britain to be exclusively “white”, is part of the process whereby racism has become rebranded in identitarian terms. It can only reinforce Muslim sectarianism.

To imagine politics not as a means of effecting social change in more universalist terms, but as a process bound by the limits of identity, is deeply corrosive.

.png) 1 day ago

6

1 day ago

6