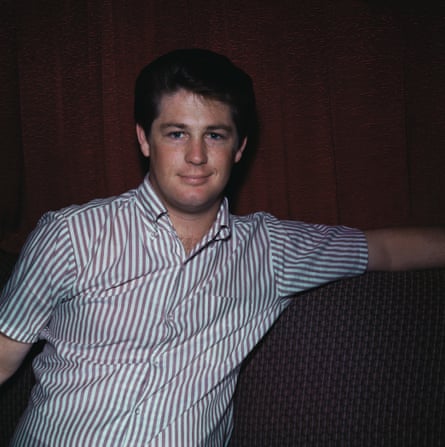

David Gray, singer-songwriter

For all the sophistication that everyone talks about, Brian never loses the thread of the song: the emotion. They have this childlike quality. These days we’d probably say he’s on the spectrum – there’s a sort of Asperger’s type innocence. He makes the lyrics and the melody speak. It’s so welcoming and without edge; it’s not part of a cynical adult world.

I knew some of the big songs – Good Vibrations and so on – but it wasn’t until a mate put me on to Pet Sounds that the penny really dropped. What he was doing in the studio is mind-boggling given the limited technology that he had at his disposal. His ear was just stellar, so he was basically remixing the songs while he was making them. He gives you so many different textures and could shape chord structures in very sophisticated, scholarly, almost classical ways, yet you never lose the feeling. The effortless way that something like God Only Knows unfolds is remarkable to me: it’s just straight from the heart and still sounds so fresh and joyful.

I can’t think of another band that created a place as vividly as the Beach Boys. It’s like they asked for our idea of California – sunshine, convertibles, milkshakes, movies – and brought it to us. But Brian didn’t surf; he wasn’t photogenic. He didn’t have the vibe, the looks … he was very awkward and looked like someone living in another world. And so how he articulated the world around him sounded otherworldly.

When I saw him at the Royal Festival Hall with the Wondermints as his band, doing Pet Sounds for the first time, he was a presence on stage, like Jesus with his disciples. They sounded so beautiful, like Gershwin or something. It was so unusual to hear oboes and clarinets in pop, but it wasn’t a novelty. They never felt stuck on; they were essential.

He would compose whole songs in his head and when he heard something, he didn’t miss. One of my particular favourites from Pet Sounds is Caroline, No, which starts with a bit of percussion that’s not even a wood block: he’d imagine these weird sounds and try everything possible to bring them to reality. And then all the noises at the end: the train, the barking dogs. My dog barks back at it when it plays.

You can hear him in everything from Pink Floyd to Radiohead to something like The Look of Love by ABC, which is definitely derived from Brian’s amazing mind. He was famously deaf in one ear, and Bob Dylan said they should put the other ear in the Smithsonian.

Jessica Pratt, singer-songwriter

I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times is one of my favourites. There’s a yearning, searching, wandering feeling … like a teenage alien come to earth. There are all these lyrics on Pet Sounds, and in this song, about feeling out of place, going to look for something and not finding it, realising that what you sought was wrong, that no one’s reciprocating, etc. A sort of juvenile, detached disappointment; there’s this mentality of “Well, I guess I’ll go kick rocks.”

But it isn’t artifice, and the music simultaneously feels as if it’s imbued with God’s infinite wisdom. When the line “sometimes I feel very sad” comes in, you nearly wince in sympathy, the way you can’t help but mirror the expression of a crying infant. You feel it in your chest. It’s a totally unique and uncanny juxtaposition – naivety meets profundity, his own spiritual blueprint.

Simon Neil, Biffy Clyro frontman

When we started, I said I wanted our band to sound like Metallica meets the Beach Boys – that was before I realised quite how sophisticated the Beach Boys were. From that point on, they’re one of the few bands that have been a constant with me in my songwriting. If ever I am at a dead end, I’ll go and listen to a Beach Boys song. It’s a book of knowledge, a religious text. Brian is a never-ending well of inspiration because of the evolution and consistency of his songwriting – he never just hit a groove, he was always finding new ways to say things.

The beauty of Brian Wilson’s songwriting is the simplicity of the complexity. A song can sound like a nursery rhyme, and when you start to actually play it on a guitar, it becomes a symphony from God. I think Wilson is a conduit for something from a different ether. His real life was in his songs – it felt like that was the world he lived in, and then he came to visit us the rest of the time. He’s not necessarily coming from the blues, he’s coming from jazz, Gershwin, everything – it was a re-education for me.

There’s a reason why you don’t walk into bars every Friday night and bands are doing Beach Boys songs, because they are so hard to play! But my wife and I, our first dance was to God Only Knows and I got the lyrics tattooed on my chest – so Biffy Clyro did a cover of it for MTV Unplugged. That was a way of trying to thank Brian Wilson. When I was trying to figure out how to do it on acoustic guitar, it made me feel like a child again, learning what a song was. I love the simplicity of the sentiments of his song – really personal and basic, hidden behind these complex musical structures, and that shows how Brian’s mind worked: in one way he was the most advanced and mature artist, and in another he had the brain of a child.

I was lucky enough to meet him in 2012, when the band were in London. I got to sit with the entire Beach Boys and speak to Brian Wilson about Sunflower, about Holland, asking him about records – to pick his brain was one of the most important moments of my life. He was a bit of a poor soul; he wasn’t at his physical and mental best. But to sit and look in the eyes of someone I genuinely feel was touched by God – that then gave me the strength to cover God Only Knows. I felt changed after having met him.

When I asked him about Holland and Sunflower he really brightened up, talked about how he had a great time out there [recording those albums]. And then the guy I was with made me show him my God Only Knows tattoo – I think that freaked him out a bit. All the Beach Boys were there, too, and to see that connection and love and protection they had for Brian even in that small hotel suite … I think that’s also why I ended up doing God Only Knows, because those guys were a band from when they were 14 or 15, and it was beautiful to see that connection. Also, Brian was a big guy – that’s something people don’t necessarily know about him, he was a bear, a linebacker. Even in his 70s he could have picked me up and squeezed me like a grape.

Ben and James in our band, singing together as brothers and twins – there’s a magic when siblings and twins sing together, and that all came from the Beach Boys. Even that sense of family, of growing together, or being with each other through the toughest of times, it’s at all levels the Beach Boys influence. And also, the story of Smile has inspired thousands of musicians – trying to make this perfect thing, and you’re not sure you’ve got there, and the people around you don’t share your vision, so your scaffolding to get there is removed. But the fact that he got back to finish that with Van Dyke Parks, it was just meant to be. That was a real big moment for all of us.

Ray Davies, the Kinks

We worked with the Beach Boys on several occasions at a time when the British Invasion was in full swing – they flew the flag for American surf music and influenced many of the British bands. Brian’s songs were more like hymns, and his body of work is up there with the greatest American composers. My condolences to his family and all who loved him.

Graham Nash, the Hollies; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young

When I was in the Hollies we played with the Beach Boys in – I think – Birmingham, Alabama in 1966 or early 67. We realised what an incredible band they were and how much fun they were having. In the Hollies we did three-part harmonies. They had at least four, maybe five voices: even Dennis [Wilson] at the back on the drums would sing.

The vocal harmonies are just unbelievable on Pet Sounds, particularly a song like Caroline, No. As I listened more, I realised that Brian thought every album should be a journey, an idea that influenced the Beatles with Revolver and certainly with Sgt Pepper’s, because that’s again a complete journey from start to finish. I think the record company put Sloop John B on Pet Sounds because they wanted a pop single. It’s a great song, but to me it doesn’t fit musically with the rest of the journey. That album changed the way many musicians thought about what music could do: it wasn’t a fast pop song, two and a half minutes right before the news. Pet Sounds changed a lot of people’s thinking, and I’ll be for ever grateful to Brian.

I think the transcendental beauty in his music was born within him in the same way it was born within Bach or Mozart, just in a different era. When Brian was writing pop music he was incredibly successful, but he was always thinking that music could be pushed further and further into the future, which is why it still sounds as fresh as a daisy.

We must remember that for God Only Knows Brian wrote the music, but [Wilson’s friend] Tony Asher wrote the lyrics. It was a brilliant combination of music and words. For me, along with the Beatles’ A Day in the Life, it’s the greatest song ever written.

Jim James, My Morning Jacket frontman

One of the biggest things about Brian Wilson was his mystery. For me, at least, when you looked at him it was like trying to understand the force behind nature or creation itself. He was so interesting because often when he spoke he never knew very clearly what he was thinking, but when he sang and wrote music, you understood profoundly and it hit you like the wind. I love the fact that he couldn’t offer in words or interviews what it was that we all felt was so magical about him, but his music came through so insanely powerfully.

Every artist longs to have their Pet Sounds – a moment that’s so important – and I’ve listened, trying to understand. What did he do? I’ve watched all the documentaries, read all the books and I know everything there is know about him, but I still can’t understand. It’s like staring at the stars at night and wondering how the universe works. Music – the creative ideas and inspiration – would just arrive in his head from wherever and then he had the technical expertise to execute these things.

When I went to be interviewed for the documentary [2021’s Long Promised Road], the people making the film asked if I would be interested in trying to write a song with Brian. Of course I was. They gave me this cassette demo of him at the piano. There were no lyrics, but the playing and melody were really beautiful. I took that home and I wasn’t coming up with much, because I wanted it to be about him, not me. Then it hit me: I should just set some of the things he’s said in interviews to music. I wrote the choruses for Right Where I Belong and then most of the lyrical information came directly from things he’d said in interviews, occasionally losing a word to work rhythmically, or whatever. Sometimes he’d look over at me and go: “Wait. I remember saying these things!” I sang a guide vocal of what I imagined it might sound like and Brian sang along with that, but then just came at it.

We all know the story of what he went through with mental illness and so on, but he conquered his challenges in so many ways and so many times. I’m sure it challenged him to the day he died, but simultaneously he had a beautiful family and a beautiful, peaceful life and a lot of people that loved him. He lived to a nice old age and his story is really one of triumph.

It was one of the great honours just being in the room with him. Most of the time we were in the studio, he wasn’t feeling very well or was quite withdrawn. But the moment we hit record and he started singing, his entire being exploded through the room. The joy shot out of his voice and it was like seeing him spring to life through music. I think it was one of the last vocals he ever did, but it had so much power. It was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

Wendy Eisenberg, singer-songwriter

Some of my earliest musical memories are of my dad covering In My Room to me as a lullaby. He was a huge Brian Wilson fan and would tell me all these cute bits of trivia about early Beach Boys, like release dates, when I was growing up. So he was just kind of elemental. And then my dad was like: here’s this foundational record, Pet Sounds, and you should listen to it. There was such a crunchy, insane, dense texture that was faithful to the songs in a way that was completely surprising – at that point, so many of the songs I had heard were arranged for maximum listenability on the radio.

I love him so much that trying to analyse his music seems almost sacrilegious. But the reason that Brian Wilson is so important to me, and why I was so devastated to hear of his passing, is that he’s touched so many people without compromising the idiosyncrasies of how he hears music, and production specifically. The narrative that I was receiving growing up, and now, was that when you play music that’s complex, it alienates people. It would make me feel that my existence as a creative person was inherently alienating. It sometimes seems like, if you’re writing a song, it has to be geared towards some ideal listener who needs to be moved by it. But the secret to a good hook or anything memorable is that you’re surprised. And Brian Wilson always knew that: no matter how honest the song is, the surprises were the things that you’d remember. And it seems like he got that from living his really hard life.

There’s a real temptation, when diagnosing Brian Wilson’s musical complexity, to say that he could have been a great composer in classical music. But the other amazing thing about him – for better and for worse, because of the intensity of his sensitivity – is that it seems like he just was where he was, all the time. So he was in California at this time, trying to live a life in music. His compositional gifts, if he were in 1571, would have sounded entirely different. He documents his world. And his world as a writer is complex, and it has a lot of heart, and it’s been through a lot, and it’s towards a childlike honesty and ethos and sensitivity.

I think about how his compositions just evolved and evolved and evolved, and became his philosophy. Like these infinite loops at the end of Surf’s Up, of vocal melodies – it’s like he wants it to be a moment of eternal purgatory or heaven. Like he doesn’t want the song to end. And he does that through an aural illusion. The lyrics there are “a child is the father of the man”, done in an Escher-type strange loop – I think he’s trying to convey the train of how we learn from each other. What I love about him is that this progression of craft is always in service of this really simple, elemental emotion, and if you get close to it, it is so complex – it contains entire worlds.

When I’m writing, I try not to judge the parts of the songs that come out conventional, and I try not to judge the songs that come out extremely complex. It’s not: I want a song to do something. It’s: I want the song that’s coming out of me to be open and vulnerable and to touch me, and also younger me and also future me. I want to be honest. And I think that’s from hearing him and how faithful he was to how the song comes out, line by line.

I keep turning to Surf’s Up, because I can’t believe it’s real – there’s a completeness to the idea that comes out when that song is done. And probably when he’s doing it, he’s having so much fun ripping from chord change to chord change or from section to section. It seems like there’s a place for him; the song is the room that he can be comfortable in and then just leap around and be like: oh my God, I’m here! And when I’m writing a song that I really love, I feel that sense of infinite possibility, and that bonds me to him. It’s like: here you are in this world that’s demanding certain things from you that freak you out or that physically harm you. But then, within this world, is a microcosm of a world that’s far, far freer. Which is what you need in this world, but it’s far, far harder to come by here.

.png) 3 months ago

48

3 months ago

48